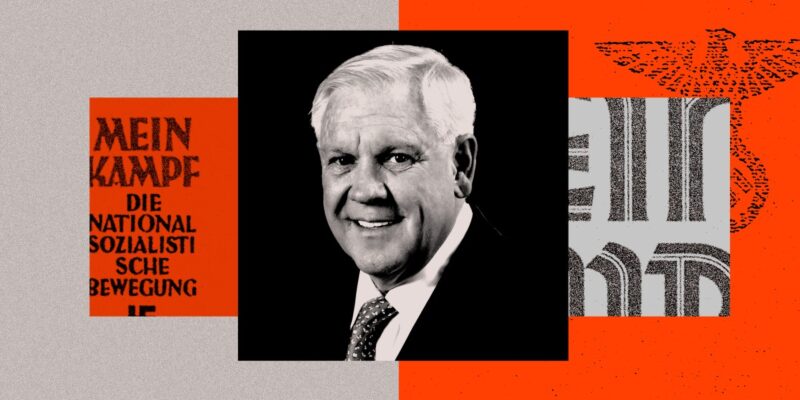

After ProPublica revealed that billionaire and GOP megadonor Harlan Crow spent decades lavishing Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas with pricey gifts and globetrotting trips, follow up stories noted Crow is an ardent collector of Nazi memorabilia and indigenous American artifacts. What’s on display at his Dallas mansion includes two Hitler paintings, a signed copy of Mein Kampf, and swastika embossed linens. Crow also has a death mask of Sitting Bull and a set of slavery-related items.

In 2014, Crow described his displays as “a historical nod to the facts of man’s inhumanity to man.” Several years later, members of a national bipartisan commission who attended a dinner at his residence were disturbed by the relics, prompting an organizer of the group to raise the issue with Crow, according to correspondence between Crow and this commission obtained by Mother Jones. Leaders of the commission now say it was a “mistake” to hold an event at Crow’s home.

In April 2019, the Commission on the Practice of Democratic Citizenship, which had been created in 2018 by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences “to explore how best to respond to the weaknesses and vulnerabilities in our political and civic life,” conducted a meeting at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. The commission was comprised of accomplished academics, artists, government officials, and journalists drawn from across the country. The evening before the session, the members dined at Crow’s estate.

“We were told he had a collection of Americana, some of it from the Revolutionary War,” says AAA&S president David Oxtoby, “and we thought that would be a nice connection.”

Crow welcomed the commission members at the door but he did not stay for the meal. The dinner was held in a section of Crow’s library where, according to Oxtoby, no offensive or controversial material was in view. But members were invited to examine the rest of the collection in other rooms, and several who did encountered disturbing items. This past weekend, danah boyd, the tech scholar and Microsoft employee who was a commission member, tweeted about that evening. She said she had been “deeply shaken by the Nazi memorabilia.” She added, “Years later, I still shudder thinking about the Nazi uniform decorations in Harlan Crow’s house. And the painting… And the ‘antebellum’ (pro slavery) artifacts.”

Ethan Zuckerman, a University of Massachusetts, Amherst professor of public policy, communication, and information, was also part of the group, and he echoed boyd’s reaction with his own tweets. He recalled, “What struck me was that Crow clearly knew there was controversy in deciding to keep Nazi artifacts in his house. In a display room off the balcony to his library was a set of swastika emblazoned dishes, silverware and linens,” he wrote, explaining that the items were behind a leather cover.

On the bus ride back to the hotel after the dinner, commission members expressed distress about what they had seen, according to Oxtoby, and its leaders decided to schedule a discussion about what had happened the following morning before diving into the established agenda. At that session, “we talked about how to make sure in a discussion of the hard points of history we can raise the issues of curatorial intent,” recalls Eric Liu, CEO of Citizen University and a commission co-chair. “Without context, you can go sideways.” During that meeting, Oxtoby says, it was decided that the commission would convey to Crow to their concerns about his collection.

A few days after the dinner—before the commission had the chance to take any action—Crow wrote Oxtoby a letter with a preemptive and defensive tone:

I was distressed to hear from [commission member and Southern Methodist University anthropology professor] Caroline Brettell that someone or some persons were offended by some of the WWII-related stuff that they discovered in my library.

For forty of [sic] fifty years now, I have collected mostly books and manuscripts but a few artifacts that relate to American history. It seems reasonably obvious to me that materials on American history would relate to the good and the bad of American history, so I do have books and manuscripts that relate to American slavery, Indian genocide, to people such as Benedict Arnold or James Earl Ray, and I have things that relate to some American opponents such as Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan and the communist states, the Soviet Union, and the Republic of China, but none of these are presented in a way that would be easy or obvious for the public to see unless someone is opening cases or cabinets where we keep these materials.

Crow seemed to be suggesting that commission members had been snooping. He continued:

But, I understand that some people were offended by the presence of these materials, and I am sorry that anyone would be offended. Anyway, I suppose everyone has their own view on these materials.

I would very much hope it would be completely obvious that having anything that related to Nazis or slavery could not possibly be interpreted as support or glorification for those evils.

Oxtoby replied in a gracious manner, thanking Crow for hosting the commission. As for the matter at hand, he diplomatically wrote,

As you noted in your letter, your collection contains items that shed light on many of these difficult chapters of our past. Several members of our Commission were distressed to find artifacts from Nazi Germany in your collection, which they saw because of your willingness to open your collection to our group. When the Commission discussed the experience, the members who raised concerns did so primarily around the fact that they encountered these items without any context from you or others that would have helped explain how they relate to the other materials on display. We should have done more work in advance of the meeting to understand the scope of your collection.

Oxtoby turned lemons into lemonade, telling Crow that the “conversations occasioned by our experience at your home proved to be of real value to the Commission as we explore how to strengthen the practice of American democracy and the institutions that support it.” He added its work had, in a way, been bolstered by the members’ interaction with Crow’s collection: “Ultimately, our experience of your collection helped underscore the essential work of the Commission to recognize the complicated past while working toward a more engaged citizenry in the future.”

A month after the exchange between Crow and Oxtoby, the three chairs of the commission—Liu; Danielle Allen, director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University; and Stephen Heintz, the president of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund—wrote members about the issue:

Those of you who were in attendance will remember our visit to Mr. Harlan Crow’s library and his collection of historical materials and objects, as well as the ensuing conversation at the following day’s meeting that arose from the discovery by some members of our group of the presence of World War II-era Nazi material in Mr. Crow’s collection as well as of racialist material from the American South. We write now to follow-up on those conversations.

During the meeting, we had a productive discussion about curatorial standards for the presentation of material from hate-groups and other controversial material—including the need for careful contextualization. We spent some time discussing how curatorial best-practices could be disseminated more effectively in support of the development of the capacity of Americans to negotiate conflicting understandings of our own history and world history. And we co-chairs pledged that we would find an appropriate way to bring the matter to Mr. Crow’s attention.

The chairs reported to the commission members that Crow had written Oxtoby to “express dismay that his collections occasioned concern.” They added, “The larger issue of how Americans negotiate conflicting understandings of our own history and of world history was with us before our dinner in Mr. Crow’s library and continues to be an important focus area for our work.”

According to Oxtoby and Liu, there was no additional interaction between the commission and Crow about his collection following Oxtoby’s reply to Crow. They do not know if Crow made any revisions to his displays after Oxtoby raised the issue of context; Crow did not respond to a request for comment.

“It was a mistake to go there,” Oxtoby now says. “We should have investigated it more thoroughly.” Liu seconds the sentiment: “It was a mistake to not understand what was at the house.”

The commission released Our Common Purpose, its final report, in 2020, offering 31 recommendations “to strengthen America’s institutions and civic culture to help a nation in crisis emerge with a more resilient democracy.” With the 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States approaching in 2026, Oxtoby looks back on the commission’s work and remembers how “we had hoped, too optimistically, in 2019 that history could be a way to bring people together. But in recent years history has become a dividing force. Maybe we were too naive.”

“We thought it could be a step toward reconciliation,” he says. As for the Crow visit? “We learned a lesson.”