On March 20, 2023, Storming Caesars Palace, a documentary directed by Hazel Gurland-Pooler, premiered on PBS. It was based on the 2005 book Storming Caesars Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty, by Dartmouth history professor Annelise Orleck, which was rereleased in an expanded edition this month. It chronicles the remarkable story of a group of poor mothers who in 1971 shut down the Las Vegas Strip in protest of welfare cuts and then founded Operation Life, one of the most successful programs of the War on Poverty era.

I didn’t know much about the women activists of Clark County Welfare Rights Organization when we first met in Las Vegas for casino Chinese food on a very hot Labor Day in 1992. A presidential race was taking place at the time, between incumbent George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton, who, among his many campaign promises, vowed to “end welfare as we know it.” In some real and still provocative ways, the women I met that day had actually fulfilled that promise in Las Vegas back in the ’70s and ’80s. These mothers and grandmothers, who were also hotel maids and kitchen staff, domestic workers, and cocktail waitresses, became incensed after a lifetime of mistreatment by violent men, field bosses, hotel supervisors, and now state and county welfare authorities. They fought back, first in a series of street demonstrations and direct-action protests, and then by creating a remarkable, comprehensive anti-poverty program in their city that remains a model today.

At the time, my first book, Common Sense and a Little Fire, a collective biography of immigrant Jewish women labor activists in the first half of the 20th century, was nearly complete. I was looking for another movement of poor women to chronicle and visiting with Maya Miller, a friend and a northern Nevada progressive and philanthropist who had been deeply involved in welfare rights work in the 1960s and ’70s. She began to tell stories about a group of women she had worked with over the previous 30 years and suggested they might have a story I’d like to explore.

Then she uttered the words every historian longs to hear. She said her basement contained a treasure trove of documents about these women and their movement that no one had yet looked at—legal filings, newspaper clippings, speech transcripts, grant proposals, and photographs. Without giving it another thought, she called the leader of this movement, a former hotel kitchen worker named Ruby Duncan, and said that I was coming to Vegas to interview her. Ruby said she could be ready on very short notice. We arranged to get together for lunch at the Union Plaza Hotel in Old Las Vegas. She said she would bring some of her colleagues, and I arranged to fly from Carson City to Las Vegas.

On the grounds of a former railroad station at the end of Fremont Street in Old Las Vegas stood a “sawdust and carpet” joint, tucked into a part of town where neon cowboys and showgirls topped hotel signs. It was a Las Vegas that my parents probably knew but one I had never imagined—more Wild West than chrome and glass glitz. Ruby would later tell me that she chose that place for our meeting because it was close to the Westside, where most of the ladies still lived. They had worked in hotels and taverns there before desegregation in 1965, occasionally finding work on the Strip, too. There they had gotten their first exposure to interracial class solidarity via the ever-powerful Culinary Workers Union. I watched penny jackpots hit by alternately desperate and elated customers in the smoky room.

Soon, a colorfully dressed line of eight Black women in their 60s entered and walked slowly toward me—clearly, they were not there for the slots. Leading the group was high-cheeked, high-voiced Ruby Duncan wearing a flowing dress she had designed. She stuck out her hand, introduced herself, and turned toward the women behind her. With a sweeping gesture, she announced, “This is Professor Annelise Orleck. She teaches history at Dartmouth College.” Then, with a dramatic pause I could see had served her well over the years, she continued, “Ladies, we are history.”

We sat at a large round table, with the soft, cyclical chiming of slots behind us, and ordered an old-timey Vegas casino Chinese lunch: egg rolls, lo mein, egg drop soup, rice and lobster sauce. And then, I began to get acquainted with the women around the table. Emma Stampley, the slow-talking Mississippi migrant, was the group’s housing expert, a tenant organizer who tried to get the women to do land banking as a way of making their organization economically self-sufficient.

Former Texan Essie Henderson, a devout Muslim, was an edgy, funny business maven—her highly successful Black beauty supply company became the proof that this poor Black women’s movement could make good use of federal Minority Business Development Agency funds to incubate vibrant small businesses. Rosie Seals, short with slicked back hair, let me know that she was the one who had founded Clark County Welfare Rights Organization in 1967. Ever after, some viewed her as the movement’s most prickly member; though, in her view, she was just making sure her comrades stayed in touch with their roots. Quiet, steady, Alversa Beals did not speak for a while but emanated a radiance that made me want to go back to hear her story. A vegetable gardener, fisherwoman, and baker extraordinaire who fed half the Westside at times when federal aid dried up, the sixth-grade-educated Beals had helped Seals found CCWRO and then, for two decades, seamlessly, professionally, and without drama ran the office at Operation Life, the anti-poverty agency the women founded in 1972.

And, of course, there was Duncan, the center of gravity who had introduced the group to me, providing running commentary through it all. A former cotton picker, and domestic and hotel worker, she was the charismatic leader who inspired a movement, and the institution builder with a genius for ferreting out just the right federal program to apply for. Duncan was the True North of everything for decades. There was only one person missing. Later I would meet the other key figure in this story: Mary Wesley, a stunning, muscular, and fearless Mississippian who unflappable welfare officials would later tell me they were afraid of. In 1992, Wesley was still raising 19 grandchildren and was otherwise occupied that first day.

The women egged each other on as they told stories. One memory lit another, and their voices became louder and louder. They laughed more and more as they challenged and affirmed each other’s recollections of the protests they had organized years before. As I look back, their outrage and eloquence are as relevant today when federal food and medical aid for the poor are under relentless attack, as they were half a century ago.

In 1967, Rosie Seals and Alversa Beals started a chapter of Clark County Welfare Rights Organization (CCWRO) affiliated with the National Welfare Rights Organization, founded by LA aid recipient Johnnie Tillmon and a former chemistry professor and CORE activist, George Wiley. In January 1971, Nevada welfare director George Miller suddenly slashed benefits for his state’s poorest families. Living on cornmeal and beans for months, these women reached the limit; no longer could they watch their children go hungry. Ruby Duncan, who was CCWRO president, contacted Tillmon and Wiley and urged them to help her plan a march on the Strip. Tillmon and NWRO Vice President Beulah Sanders had taught Ruby that the best way to get powerful people to sit up and listen is to “hit them in the ‘picketbook.’” Driving up the Las Vegas Strip one night, Duncan mused, “This is the pocketbook. This is the main vein.”

Wiley, Tillmon, and my friend Maya Miller—who was then with the National League of Women Voters—helped Duncan and the women of CCWRO plan what they called Operation Nevada. It became a movement that drew armies of young poverty lawyers, welfare recipient activists from around the country, and allies in the clergy, civil rights movement, and even in Hollywood to Nevada to launch a class action lawsuit against the state for violating recipients’ rights with the cuts. They also planned to stage a march on the Strip. Wiley and NWRO co-founders, social scientists Richard Cloward and Frances Fox Piven, believed that welfare recipients could win concessions from the state through street protests and civil disobedience. For the next two years, the women of CCWRO did exactly that.

A demonstration outside the Las Vegas Sands casino and resort in March 1971. Led by Ruby Duncan, they are protesting the state’s decision to slash welfare benefits and reduce the number of claimants. One placard reads “Nevada Starves Children.”

American Stock Archive/Archive Photos/Getty

The group organized a march on the county welfare office a few months after the state cut off aid to their families. After the boyish Las Vegas Welfare Director Vince Fallon refused to meet with a crowd of women who were waiting in the streets below, Alversa Beals lifted him and threw him over her shoulder—“like a sack of cotton,” Essie Henderson shouted—and carried him down the stairs to the street. Waiting there were hundreds of aid recipients he had cut off to tell him just what it was like to face children who had not had enough food for months or a pair of decent shoes to wear for the first day of school.

In March, the group led thousands of welfare mothers in protest. Their kids and allies marched down the neon-lit desert highway that had become a postwar sprawl on psychedelics known worldwide as the Las Vegas Strip. They had asked movie stars Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, feminist icon Gloria Steinem, world-famous baby doctor Benjamin Spock, civil rights leaders Ralph Abernathy, and labor organizer Cesar Chavez to join the march to attract press coverage and, more importantly, ensure that no casino mobster or right-wing cowboy decided impulsively to shoot into the crowd.

They passed open-mouthed tourists and angry Nevadans shouting “Get a job.” And then they stormed into Caesars Palace Hotel and Casino—the country’s gaudiest shrine to conspicuous consumption. Their march on Caesars was simultaneously an act of desperation by hungry moms and kids and at the same time a lively takedown of middle-class American consumer culture. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy, then the leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, paused their march for a few minutes to preach to a giant white statue of Caesar astride a white horse. “Caesar, give unto the poor what is rightfully theirs,” he boomed. Essie laughed as she described how anxious tourists and employees scrambled for cover. “They were hiding the furs and locking away the jewels,” she said. “They couldn’t imagine that we weren’t there to steal something.”

These women who washed kitchen floors and cleaned hotel bedrooms in Caesars, the Flamingo, the Sands, the Stardust, and other iconic 1970s Strip hotels remembered their kids splashing in Caesars’ fountains, cavorting in the gold-leafed lobby, and running their skinny arms over the red velvet craps tables. They vowed to march again the following weekend if their benefits were not restored. It was March 1971 and for the first time in the history of Las Vegas, gambling on the famed Strip shut down, costing casino owners untold sums of money and the state a whole lot of tax revenue.

Unlike so many protest marches of that era, this was more than a flash on the desert sand. It was the beginning of a long campaign of civil disobedience. For the next two years, poor mothers staged eat-ins at Strip hotels where all-you-can-eat buffets bustled with tourists. They organized read-ins in white neighborhoods because the Las Vegas library district refused to open brick-and-mortar libraries in Black parts of town. And they sang civil rights songs outside the home of the Las Vegas welfare director just after dawn. “Hope you are enjoying your breakfast while our children have nothing to eat,” they chanted.

They even showed up in the backyard of the Governor’s mansion in Carson City, as Mike O’Callaghan swam his daily laps, demanding to know if he really didn’t have money to feed their hungry children and chastising him for allowing Miller to again cut off their aid. The governor suggested that they “get out of the streets and learn how to work the system.” As they laughingly reminded me, when it came to working the system they “did it better” than anyone expected them to and better than any welfare professionals with whom they had ever interacted.

After their foray into the governor’s mansion, the women decided to lay claim to the shuttered Cove Hotel, once co-owned by entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. and boxer Joe Louis. On the Westside, it once was a lively place of midnight jam sessions with the likes of Lena Horne and Nat King Cole before the city integrated the Strip in 1965. But it had become a derelict building that served mostly as a crash pad for junkies and homeless vets. Together with their kids, brothers, boyfriends, and neighbors they stripped siding and fixed the roofs, painted moldy walls, and patched pipes.

With the help of Legal Services attorneys Jack Anderson, Mahlon Brown, and Marty Makower, the women envisioned a “one-stop shopping” center for social services on the Westside. Its slogan would be, “In the poverty community, of the poverty community, for the poverty community.” And so the transformed Cove Hotel became a vibrant community center and clinic so that harried poor moms no longer had to drag their children to three different parts of town for food aid, health care, and job training programs. Aided by attorneys, preachers, League of Women Voters, and Democratic Party activists, this group of welfare moms applied for and won federal grants to open and run this, the first health clinic in the largely Black, and thoroughly poor Westside of Las Vegas. Then came the neighborhood’s first library, public swimming pool, senior citizen housing project, solarization program, crime prevention program, and community newspaper, all organized and staffed by poor mothers and later their young adult children.

Welfare Rights Organization march on the Las Vegas Strip on March 6, 1971.

Clinton Wright Photographs/UNLV Special Collections

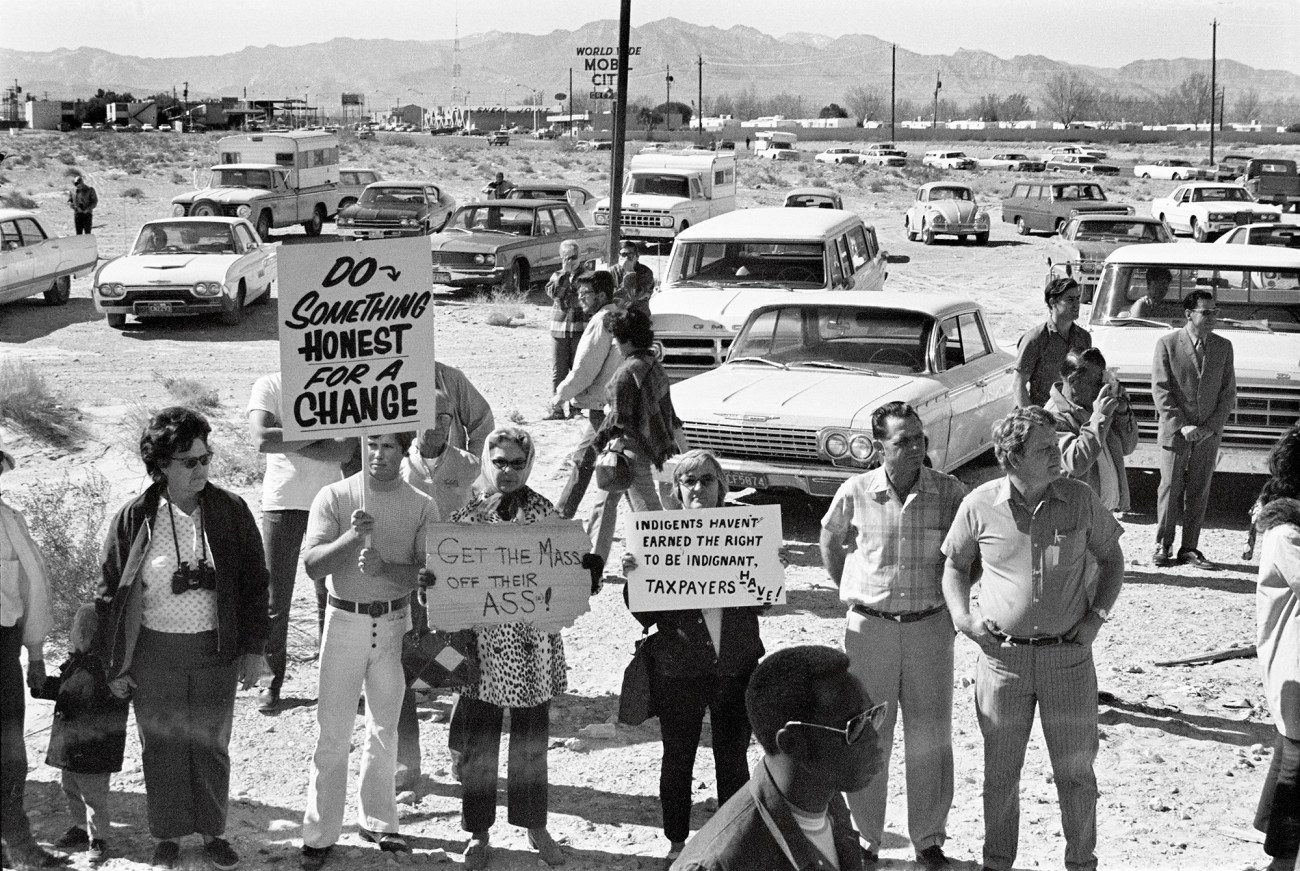

Counterprotesters at the Welfare Rights Organization.

Clinton Wright Photographs/UNLV Special Collections

Despite Richard Nixon’s cuts after 1969, War on Poverty funds still flowed freely from 1964 into the early Reagan years. Ruby Duncan proved unmatched in finding programs that the Westside needed and that the women of Operation Life could run. Along with organized welfare moms in 16 other states, they sued the federal government to release funds for the Women and Infant Children (WIC) nutrition program and to make Food Stamps a truly national program. Emboldened by their successes, Ruby went to Washington, DC. She haunted the halls of government agencies and found one program after another that she thought would benefit poor Las Vegans. “We can do it and do it better,” became their motto, as they developed ever more successful programs run by and for poor Nevada families.

They also received money from the city, the county, the state, and private foundations. They named their project “Operation Life—before Life got a bad name,” Ruby quipped. All of the War on Poverty programs were Operation This or That, Ruby recalled. They chose the word “Life” for theirs because they felt they were literally fighting for their lives.

Operation Life emerged during an era of unparalleled creativity in fighting poverty across the United States. From Los Angeles to Baltimore, from Texas to Minnesota, community-based organizations—funded by War on Poverty Community Action Program and Community Development Program dollars—opened a dynamic array of community groups: A Chicana-founded feminist health clinic in LA; a self-help program run by Black public housing tenants in Baltimore; an agency to build affordable housing in New York’s Chinatown run by college-educated kids of immigrants; clinics run by varied multi-racial community coalitions in Raleigh and Memphis; a social service agency to help Tejano farmworkers who had migrated to Milwaukee. But despite all of this creativity, and a burst of organizing that studies later showed literally extended life expectancy in poor neighborhoods across the country, no other group lasted as long as Operation Life or was run by poor mothers themselves. Ruby Duncan would recall attending a meeting of Community Development Corporation executives in Washington, DC, and saying: “There were people of all colors and speaking all kinds of languages in that room. But I was the only woman of color.”

Alversa Beals in front of Operation Life

/Ruby Duncan

From the day that it opened in 1972 and for 20 years after, the agency not only offered health care and food. It also provided jobs for poor women and their kids, delivering desperately needed services to their neighbors. When Johnnie Tillmon organized the nation’s first welfare rights group in Los Angeles in 1963, she sought to prove that poor mothers were the real experts on poverty and how to alleviate it. Operation Life took that vision and ran with it. Their programs proved to be more effective than those run by traditionally credentialed experts. Operation Life Clinic served a higher percentage of eligible poor children than any federally funded pediatric clinic in the nation. When asked in 1973 by then-Health, Education and Welfare Secretary Casper Weinberger how they did it, the women said: “That’s easy. We care about the kids. We consider them our children.”

By 1978, after they had been open for just six years, Operation Life employed over 100 people and was managing more than $7 million in public and foundation funds annually. Marty Makower first met the women before the Strip marches in 1971, decided to go to law school to help them achieve their goals, and stayed part of their movement for the next 20-plus years. Given how poor and disfranchised these women and their kids were, she says, “This was kind of unbelievable.”

Ruby liked to say Operation Life “got women off welfare and into good jobs,” a goal espoused by grandstanding politicians like Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton. But unlike these Washington policymakers, Ruby pointed out, they did so not by forcing aid recipients into demeaning make-work jobs (like picking up garbage in city parks—a favorite of New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani) but by giving poor moms work they were eminently qualified to do: assessing the needs of their families and their community and providing aid. Ruby said her political philosophy could be summed up this way: “What any mother wants for her own children, a humane society should give to all kids.” For a few shining years, recalled movement veteran Roma Jean Hunt, “We were important—to the neighborhood, to our people, to the country.”

Still, for all the joy at what they accomplished, by the early 1990s it was all coming apart. Just three weeks before I met them, the organization these women had worked so hard to build had been stripped of federal funding. It had served tens of thousands; why would the programs be taken away?

Protesting is vibrant and acute. Building a sustainable new world is brutal, hard work. Federal, state, and city officials who they say had long been both jealous and contemptuous of the women’s success began to push them out of the clinic, out of the library, out of the job training programs. It was happening all over the country, Operation Life board member and former state Rep. Renee Diamond told me. Genuinely grassroots women-run groups were audited on phony fraud charges and forced out as programs they had worked so hard to build were handed over to social service professionals with MSW, MPH, and MBA degrees.

State and city officials had dragged Ruby and the women into court more than once over the years trying to prove they were guilty of fraud. They never did. In one federal WIC audit, investigators found that the financial records, kept by elementary-school-educated Alversa Beals, were accurate almost down to the penny. The only discrepancy auditors could find was for 4 cents. But such outcomes did nothing to calm the hostility that so many politicians felt toward this poor-mother-led agency.

When a new group won a federal contract to run a clinic on the Westside in 1992, the women told me, they literally “ripped the sinks out of the walls,” Ruby said angrily. “And they left champagne bottles in the trash,” Mary Southern spat. “They wanted us to know they enjoyed it.” The usually effervescent Mary Wesley was bitter and downcast. “I guess we were smart enough to bring in the government programs, too dumb to keep running them.”

When Storming Caesars Palace first came out in 2005, it was a bleak time for activism. The country was still living in the shadows of 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina. President George W. Bush announced plans to end funding for community development corporations like Operation Life. He diverted federal poverty funds originally intended for job training for poor mothers into conservative pet projects like the African American and Hispanic Healthy Marriage Initiatives. Founded on the premise put forth by Heritage Foundation analyst Robert Rector, the initiative worked on his claims that the best way to fight poverty was to guide single moms into heterosexual marriages.

Ending community development block grants never happened. The programs that women leaders in the welfare rights movement had fought to bring to their states had become essential to tens of millions across the country. But the Healthy Marriage Initiatives did. The focus was intended to obscure the fact that a majority of poor mothers who applied for aid in the 1990s, and later, did so because they were fleeing abusive husbands. As Mother Jones reported, “Originally championed by Republican lawmakers including Iowa Sen. Chuck Grassley, former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum, and current Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback, a federal initiative to promote marriage as a cure for poverty dumped hundreds of millions of dollars into programs that either had no impact or a negative effect on the relationships of the couples who took part, according to recent research by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).”

In the nearly 20 years since then, we have moved to a dramatically different political climate in which street protest and a belief in progressive legislation have been revitalized by Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, Fight for $15, and a resurgent labor movement. A new generation of activists in Las Vegas and elsewhere has begun to cite the example of Operation Life to help others understand on whose shoulders they stand, in part using the same organization, the Culinary Union. At the same time, the assault on entitlement programs has grown even more intense, with the House GOP majority this year vowing to slash funding for Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the latest name for food stamps.

Over 13 years of conversations with the women from Operation Life, I saw their pride. Alversa Beals liked to say she had been “ready to ride back in the day” when Ruby called. “I still would,” she said quietly. “I still would.” Many days it feels as if we could be back in 1973 when Ruby Duncan and Coretta Scott King were telling legislators that “violence is a hungry child.” When poor mothers shape and guide anti-poverty programs, they can succeed beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. The women of Operation Life swore they could “do it and do it better.” And they did.

All of the women are gone now except for Ruby, who at nearly 91 is still clear as day; from time to time she offers commentary in the Nevada press about the challenging politics of our times. She and the other women were saddened but not surprised by the revival of conservative attacks on the poor. Young people stopped them on the street to ask, “When are you going to start up again?” They replied, “It’s your turn now.” One homelessness and living wage activist Minister Vance Stretch Sanders was assigned this book in college and has been acquainting young Black Las Vegans with it every chance he gets. “I’m so proud to stand on the shoulders of Ruby, Alversa, Mary, Emma, Rosie, and Essie,” he says.

During the pandemic, Sanders started “Mary Wesley’s Ride Community Grocery Program” to deliver food, soap, shampoo, toothpaste, and blankets to Las Vegas homeless. Mary’s daughter Yvonne said, “My mom’s up there in heaven turning over, flipping, doing cartwheels just to see..something like this.” Emma Stampley’s great-granddaughter Carmella Gadsen, now a homelessness and LGBTQ rights activist, says that she and other activists of her generation continue to be inspired by her grandmother and the women of Operation Life. “Fighting for a future that dignifies all of us—our labor, our humanity, our whole selves—is what my grandmother and these incredible women committed themselves to in their generation,” she says. “It’s the same work I’m committed to now.”

In West Las Vegas, there is a shiny new library and performing arts center brought by the women of Operation Life. There are medical facilities where before there were none. And in 2011, a man named Michael Flores, who had read my book in high school, achieved his long-standing goal to get an elementary school named for Ruby Duncan. The school stands in one of the poorest areas of the Westside. Powered by solar panels—a cause the women of Operation Life had championed 50 years ago—the school’s promise is that it will train a multiracial student population to solve the problems that still plague the poorer parts of the city in the only way that makes sense: by organizing from the ground up.