On a rainy day in late March, a group of American and European public intellectuals gathered in a stone-clad villa in Budapest’s Castle District. They’d been invited by the Danube Institute, a conservative think tank backed by the Hungarian government, to denounce growing threats from the left. The institute’s president, John O’Sullivan, a British octogenarian and former editor of National Review, summarized the challenge—gender theory, recognition of a climate emergency, critical race theory—in one all-purpose expression: “wokeness.”

The mastermind behind the event, titled “The ABCs of Critical Race Theory & More,” was American activist Christopher Rufo, who came to prominence for instigating the moral panic over CRT in public education—a move that, O’Sullivan noted approvingly in his introduction, “provoked a popular resistance of parents.” Rufo had recently arrived for a monthlong visiting fellowship with the institute, an incubator for US ideologues who consider Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s brand of nationalist populism—particularly Orbán’s muscular use of state power—as a model to be replicated. Orbán’s “illiberal democracy” has subjugated the independent press, banned LGBTQ content from schools, ended gender studies in universities, and evicted the Central European University from Hungary. This last effort had the dual benefit of exiling a global postcommunist bastion of liberal values, social sciences, and humanities while eradicating the influence of its founder, Hungarian-born philanthropist George Soros, whose extensive financial investments in upholding democratic institutions throughout former communist countries have been demonized, often in blatantly antisemitic ways, by the right in both nations. (In an interview, O’Sullivan defended the institute. “We are not doing anything mysterious,” he said, describing its mission as to “encourage the transmission of ideas” and “democratic debate.”)

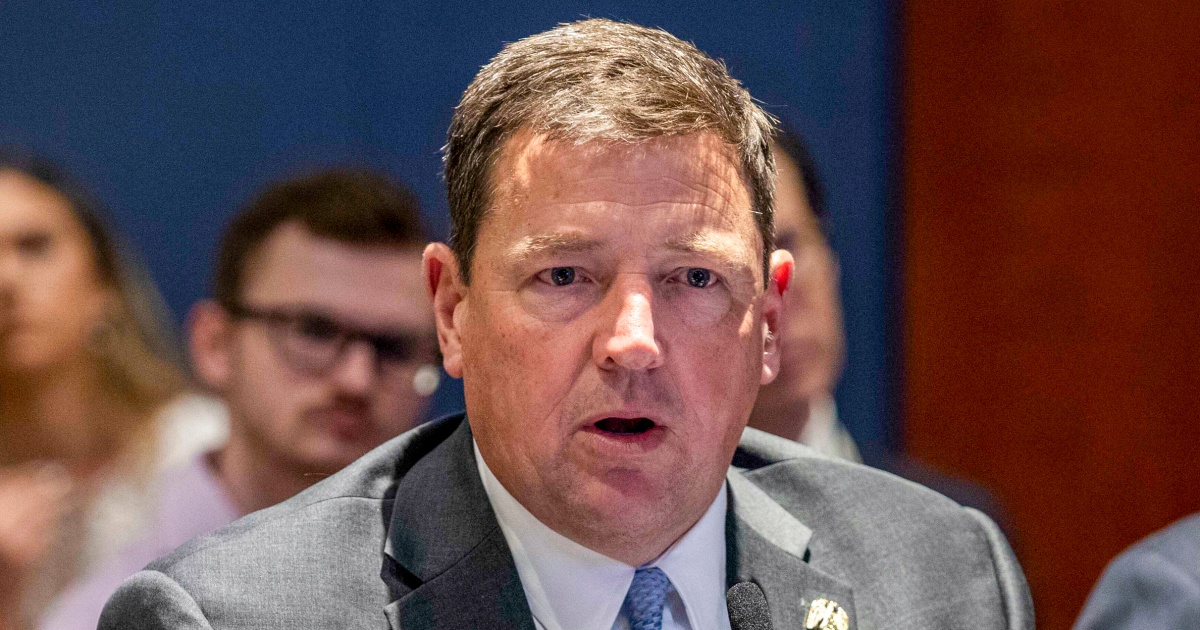

Displaying a fresh high and tight haircut, the 38-year-old Rufo took the stage with the swagger of a classroom know-it-all. CRT—which he describes as a race-centered, neo-Marxist version of history pushed by elites perpetuating a myth of the US’s intrinsic racism—might seem like a uniquely American construct. But Rufo warned that, much like Netflix, rap music, and other Yankee exports, CRT would inevitably land in Hungary. “You should prepare yourselves politically,” he said, “prepare yourselves intellectually, and not rest on the assumption that because it’s a false theory and because it can’t be transposed accurately onto your history—it always finds a way.”

In 2020, Rufo’s highbrow brand of scaremongering launched him into the conservative spotlight. He boasts that his strident anti-CRT campaign was a singular achievement in public persuasion—a transformation from “an obscure academic discipline” that few had heard of into a catalyst for conservative outrage. Not one for false modesty, he told the New York Times, “I’ve unlocked a new terrain in the culture war.”

When Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis began his own attacks on CRT in March 2021, Rufo welcomed him to the fight. Rufo assumed an unofficial role advising the 2024 candidate, helping DeSantis build his culture warrior reputation with Orbán as his exemplar. (Rufo admits he sees similarities between some policies in Hungary and the Sunshine State, but claims “if there is a direct inspiration, I am not aware of it.”) Where DeSantis—or Donald Trump with his reality-show populism and “build that wall” chants—often comes across as an unpolished bully, Rufo provides a veneer of intellectual sophistication and an arsenal of strategically incendiary rhetoric. As Politico’s Michael Kruse writes, Rufo is a “main source and surrogate” for the governor’s “anti-woke” agenda.

With CRT, Rufo effectively distorted an academic and legal framework that examines how racism is embedded in institutions and laws into a concise acronym and conduit for white grievance. To Jennifer Mercieca, a historian of American political rhetoric and professor at Texas A&M University, he’s a propagandist whose talents call to mind Edward Bernays, the so-called father of public relations, who in the late 1920s famously sold cigarettes to women by associating smoking with freedom. “He’s very savvy about how to move ideas into the public sphere in order to control the political conversation,” Mercieca says. Rufo frames “the conversation in a very specific way so that the outcome is predetermined.”

Christopher Rufo describes himself as an accidental activist and lapsed liberal. An only child, he grew up Roman Catholic in an Italian-speaking home in Sacramento, California, with lawyer parents; his mother hailed from Detroit and his father—born in the small Italian village of San Donato Val di Comino—was involved in Democratic politics. Rufo sometimes visited his “dedicated Marxist-Leninist, unreformed communist” extended family in Italy, and they once gifted him a Che Guevara flag that he hung in his bedroom. “I thought it was pretty cool at the time,” he’s said.

High school teachers pegged him as arrogant but bright, the kind of student who would ignore lectures but still ace the Advanced Placement exam. “He completely tuned me out, sat there and read a book,” recalls Gary Blenner, who taught Rufo AP History. “He was just dismissive of anything I had to say.” As a Georgetown undergrad, Rufo initially joined progressive groups and marches against the Iraq War, before growing disillusioned with what he once described as the “pervasive phoniness” underlying “the elite left-wing agitation on campus.” He was turned off by “sons and daughters of America’s elites,” who were bound to “take off the keffiyeh or the red bandana and become investment bankers.” In interviews with fellow conservatives, he recounts his conversion from being “very young and very excited” and “very anti-authoritarian” to classical liberalism. (In his 2023 book, DeSantis similarly attributes his rightward shift to Yale’s “unbridled leftism.”)

After graduating in 2006, Rufo embellished his experience to land a gig as a cameraman for filmmaker Cody Shearer, a Clinton family associate he had met at a grocery store. They traveled to Cyprus for a project but, after a falling-out, Rufo reportedly kept Shearer’s equipment—an allegation he denies—and recruited a longtime friend to film a travelogue through Mongolia. Rufo told the Sacramento Bee in 2007 that he “used tactical exaggeration” to get an interview with the country’s president. The final product aired on public television; a New York Times review said Rufo and his co-creator had “a good eye for the unusual,” but made “the mistake of thinking that they are as interesting as the people they are documenting.”

Rufo directed other documentaries on relatively anodyne topics such as the Senior Olympics and baseball in China. But a five-year project about poverty in “three forgotten American cities” set him on his current path. Following residents of Youngstown, Ohio; Memphis, Tennessee; and Stockton, California, he witnessed “wrenching human situations” of gun violence and incarceration. “Spending a lot of time looking at real life in the poorest and most desperate communities,” he has said, sparked “a huge internal change.”

His documentary America Lost opens with sentimental home movie footage—Rufo’s young parents holding hands and walking, his father cuddling infant Chris. Rufo narrates how he was “born into the American Dream,” where his penniless immigrant father gained a life of prosperity. Then his tone becomes ominous, and family archival images are replaced with what he calls “the lost American interior”—night scenes of police cars, ambulances, and homeless people. “We are coming apart economically to be sure,” he says, “but we are coming apart as a culture.” As the film progresses, he describes these places as suffering on a “deeply personal, human, even spiritual” level, one hastened by the erosion of religious community and the two-parent family. He hoped the movie—which received funding from right-wing foundations that support the Manhattan Institute, where Rufo now leads an anti-CRT initiative—would “reshape the way we think about American poverty.”

“I started the film as a libertarian,” Rufo said during a 2020 online screening, “and I finished the film as a conservative.” Along with his political evolution, Rufo was contemplating a career change. In his telling, the left-leaning documentary space had become inhospitable for a newfound conservative. He had relocated to blue Seattle, where his Thai-born wife, Suphatra, had a job with Microsoft, and he found an intellectual home within a right-wing network always ready to bring a professed convert into the fold. He secured a 2017 Claremont Institute fellowship (same class as Project Veritas founder James O’Keefe) and a role with the Discovery Institute, a think tank based in his new hometown and known for promoting the anti-evolution concept of “intelligent design,” becoming director of its Center on Wealth & Poverty. Rufo also started writing for the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal and later landed a fellowship with the Heritage Foundation, whose president, Kevin Roberts, would go on to describe him as a “master storyteller” of the conservative movement.

“My whole world opened up,” he told psychologist and conservative guru Jordan Peterson. “I felt like I had the freedom to think for the first time as an adult.” While making a movie took years, channeling his storytelling skills toward commentary on social justice and political issues offered more instant results.

For Rufo, progressive Seattle became a convenient punching bag. His work for the Discovery Institute and City Journal focused on the city’s homelessness crisis, criticizing the “ruinous compassion” of “socialist intellectuals” who pushed for more housing as a salve. “We must look at homelessness not as a problem to be solved, but a problem to be contained,” Rufo wrote in October 2018. “The backlash is coming,” he predicted.

That year, Rufo filed to run for a Seattle City Council seat held by a progressive incumbent. Around that time, he styled himself as a “centrist.” But he soon dropped out of the race, claiming he and his family had been harassed. Rufo shared hostile social media posts, calling him a “fascist” and “a sad excuse for a human being,” with reporter Katie Herzog, who was then with the Stranger. He also said someone had sent his wife a message containing a threat of sexual violence. Herzog recently said on her podcast she thought Rufo had exaggerated the harassment to “make himself look like a victim of crazy leftists.”

“We’ve ceded the intellectual and moral territory to misguided principles of tolerance, diversity, and compassion,” Rufo complained after his abortive run, suggesting his opponents’ attacks had betrayed those ideals. He returned to writing, skewering Seattle’s “activist class” and the “radical progressive ideology seeping its way through institutions.” In 2019, Rufo broke into the major leagues when he was invited three times to appear on Tucker Carlson’s show to comment on Seattle’s supposed descent into lawlessness.

Rufo’s burgeoning platform coincided with the rapid growth of a social movement that he would harness to further boost his career. In the summer of 2020, he watched as demonstrations sparked by George Floyd’s murder swept the country. In Seattle, protesters set up a cop-free autonomous zone whose utopian vision was soon marred by shootings and other crimes. Rufo characterized it, and the summer of 2020 more broadly, as a “period of violent terror” and pointed to the Seattle activists’ experiment as the perfect example of the left’s failure to deploy the tenets of CRT into something resembling governance. “Beware of clever slogans,” he said of the Black Lives Matter movement at the time. “They often mask malign intent.”

With Seattle continuing to serve as his anti-woke lab, he became a regular on Fox, bashing the city’s anti-bias initiatives as racist. On Twitter, he called himself a “reporter with a mission to defend America” with “bombshell” whistleblower-provided reports about CRT in federal agencies and school districts. The more he wrote, the more sources sent him information he could use, and the more he built the case that CRT was pervasive, unpopular, and “coming soon to a city or town near you,” as he wrote in City Journal. Within months, Rufo’s Twitter following had more than tripled, and he added the swashbuckling and combative image of crossed swords to his bio on the platform. Meanwhile, Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck highlighted his work and Rufo continued his TV appearances. But even more opportunity beckoned. In one interview, he said the BLM movement “was like a lit match into gasoline” that, combined with pandemic-fueled rage over government overreach, had “created this gap, this void, where people were calling out for new voices and new ideas and new defenses—a new language.” All he had to do was legitimize their anxieties by introducing a vocabulary to express them.

On September 1, 2020, Rufo staged a well-rehearsed coup de grâce on Carlson’s Fox show. While denouncing how CRT had become the “default ideology of the federal bureaucracy” and an “existential threat” to the country, he called on then-President Donald Trump to immediately abolish “critical race theory trainings.” The president apparently was watching. In his White House biography, then–chief of staff Mark Meadows writes that he called Rufo the next morning and began to work on an executive order. Rufo flew to Washington to help “fine-tune the wording,” and on September 22, Trump signed the order instructing federal agencies to stop racial sensitivity programs. (President Biden rescinded it upon taking office.) Rufo reportedly kept the pen Trump used and a handwritten card that read “Who says one person can’t make a difference?!” After Meadows’ book was published, Rufo tweeted to thank him for including the anecdote, adding that “the Tucker-to-Trump pipeline was a beautiful thing!”

Rufo catalyzed a national movement, from Trump down to the parents who packed once-sleepy school board meetings, decrying award-winning books as pornographic and brandishing signs declaring they would not “co-parent with the government.” Conservative school board candidates found financial and mentoring support from newly formed, deep-pocketed national groups. Legislation to restrict discussions on race, gender identity, and sexuality spread, spurring campaigns to defund libraries and ban books. If his goal was to mobilize the public, it worked.

Rufo’s home studio in Gig Harbor, a small maritime town near Tacoma, has a direct connection to Fox News’ satellite desk. There he records highly produced, professorial video essays for his YouTube channel, including a series dubbed Christopher Rufo Theory—a play on CRT—that he promotes to more than half a million Twitter followers and shares with thousands of paying Substack subscribers. Rufo welcomes monikers like “far right mastermind” as “dangerous and cool” and makes a point of antagonizing the media. “I’ll give you the position as the most prestigious Christopher Rufo theory scholar,” he quipped during an appearance with Joy Reid on MSNBC after she called him out for twisting the real meaning of CRT. He once refused to speak with USA Today unless the reporter removed gender pronouns from her email signature for 90 days. When I reached out for an interview, an aide said he wouldn’t have time, and did not respond to follow-up emails. Later, in response to a detailed list of questions, Rufo sent a terse reply. “My official statement: Mother Jones is trash,” he wrote.

Rufo has mastered the art of erudite name-dropping, citing books like Milton Friedman’s Free to Choose and Augusto Del Noce’s The Crisis of Modernity, and referring to James Burnham, a Trotskyite who turned anti-communist and helped found National Review, as one of his “intellectual heroes.” But more often, he invokes leftists like Herbert Marcuse, Rudi Dutschke, or Angela Davis, crediting them with a victorious “long march through the institutions” that has infiltrated powerful organizations—from elementary schools to state universities, from media to corporations. (His upcoming book about “how the radical left conquered everything” has the same editor as DeSantis’ recent memoir.)

In Rufo’s diagnosis, Reaganites and the “think tank right” kept their main focus on economics for too long and failed to engage with the culture wars. Rufo considers himself to be launching an anti-establishment, “rock and roll” counterrevolution, dueling with crossed swords to reclaim territory lost to progressives. Conservatives must “take the linguistic high ground,” he says, and put forward a new “moral language.” He explained his rationale for focusing on critical race theory to the New Yorker: “political correctness” was dated, “cancel culture” too vacuous, and “woke” overly broad. CRT was the “perfect villain.”

“He has a Ronald Reagan–level skill in manipulating language for political ends,” says Rick Perlstein, the author and historian of modern conservatism. “Rufo is the Svengali for the age of Trump,” he adds. “He is perfectly willing to push the envelope of brazenness in a way that wasn’t conceivable in the era of Nixon and Reagan.”

In that sense, Perlstein explains, Rufo “seems to be a product of a world that is very comfortable with outright reaction, that sees the institutions of small-l liberalism—and even democracy itself—as impediments to a vision of reactionary triumph.” Indeed, Rufo is welcomed in the eclectic big tent of the new right. In 2021, he spoke at the National Conservatism Conference in Orlando, an event “dominated by the psychology of threat and menace,” according to a report by David Brooks in the Atlantic, and whose participants were eager to use government to put conservatives in power. Rufo later signed a follow-up NatCon manifesto rejecting globalism and elevating Christian values—“a road map for autocracy,” as Salon described it—drafted with the help of US admirers of Orbán. For Nicole Hemmer, a Vanderbilt political historian and author of Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics, the US right’s growing affinity for Hungary suggests “a hunger for a much more powerful state that can shape the world that they want to live in through force.”

Among the crowded field of hyper-online right-wing provocateurs, Rufo stands out for his willingness to publicize his strategy even as he is implementing it. “We have successfully frozen their brand—‘Critical Race Theory’—into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions,” he famously tweeted in March 2021. “We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category. The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘Critical Race Theory.’ We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.” Similarly, in June 2022, he proposed that instead of saying “drag queens in schools,” conservatives should use “trans stripper” to shift “the debate to sexualization.” That way, the left “will find themselves defending concepts and words that are deeply disturbing to most people.”

“That kind of overt explanation of his process and his goal is something you don’t often see,” Hemmer notes. “Normally, you have to kind of read between the lines…Rufo is just very open about it.”

In April 2022, Rufo previewed the next phase of “laying siege to the institutions” in an address at Michigan’s Hillsdale College, a conservative breeding ground with deep ties to the Christian right. “We defund things we don’t like,” he said. “We fund things we do like.” One tactic is to push state legislators to adopt so-called “curriculum transparency” bills aimed at toning down the teaching of concepts controversial on the right and other legislation to do away with DEI initiatives.

Rufo sees himself as a “hands-on political activist,” Hemmer says, who wants “to change politics in the United States”—and be around powerful people who might make that happen. So when Florida’s governor declared a war on “woke” that would extend to Disney, Rufo made common cause with his project. Trump may have paved the way, Rufo wrote, but DeSantis possesses the skills and courage to move from “culture war as performance” to “culture war as policy.” The governor acknowledged Rufo’s work while successfully pushing the state Board of Education to ban CRT in the summer of 2021. That December, Rufo accompanied DeSantis as he announced his Stop WOKE Act, which restricted discussions on race in schools and workplaces. When he signed the bill the following spring, DeSantis praised Rufo as the “architect of focusing attention on some of these pernicious ideologies.”

On January 25, 2023, Rufo and Eddie Speir, the founder of a private Christian school, held town halls with faculty and students at the New College of Florida in Sarasota. They were among six new conservative trustees appointed by DeSantis to the board of the 700-student public college, which prides itself as “a community of free thinkers, risk takers, and trailblazers” and as a haven for queer students. But for Rufo, it was a “social justice ghetto” ripe for the seizing. “We are now over the walls,” he said of the appointment.

College officials received an email threatening violence against Speir and tried to cancel the forums, but Rufo, in a confrontation that he later released on video, accused them of suppressing free speech. “This is the problem at your school. You know that, right?” Rufo told the provost. “You’ve created an environment in which the most intolerant and the most aggressive people who threaten violence can veto you, can veto the president, can veto any changes.” When the provost said the school would close the building, Rufo and Speir pulled rank and refused to leave.

Rufo told the staff packing the auditorium that the progressive college’s “echo chamber” culture had doomed it to struggle with enrollment and retention. He referred to himself as a “drastic solution to a crisis.” One audience member shot back, saying he was the “problem.” Chief diversity officer Yoleidy Rosario-Hernandez, who uses ze/zir pronouns, asked for assurances that “people like myself will maybe not be fired next week.”

Rufo also told the New College community that his goal wasn’t to replace the “left-wing orthodoxy with the right-wing orthodoxy.” But students like Sam Sharf, a transgender second-year sociology and gender studies major, remain skeptical. “He is smart enough to be able to posit himself as a serious intellectual,” she says, “but he advocates for things that are very harmful.” Amy Reid, the school’s director of gender studies, worries about “generations of students not so much being educated, as having blinders put on them by institutional forces.”

At the end of January, the new board held its first public meeting and wasted no time in carrying out a plan to transform the small honors college into, as DeSantis’ chief of staff put it, the “Hillsdale of the South.” They voted to oust Patricia Okker, the incumbent president and first woman to serve in the role, and moved to replace her with Richard Corcoran, a onetime Republican speaker of the Florida House of Representatives and DeSantis’ former education commissioner.

Outside, students rallied in support of Okker, chanting “Save New College” and waving signs saying “Protect educational freedom” and “Our school, our home, our choice.” “We are the petri dish for the rest of the nation,” warns Tamara Solum, who attended the board meeting and whose daughter graduated from New College in 2020. “If [DeSantis] runs for president in 2024 the country needs to know what he is capable of.”

Earlier that day, DeSantis hosted Rufo at a press conference where the governor unveiled his statewide overhaul of public higher education, promising to purge “ideological conformity” and DEI, while advancing a Western-centric curriculum. Rufo took the stage and congratulated DeSantis for reasserting control over public institutions. Since then, New College’s provost stepped down. The librarian, a member of the LGBTQ community, was dismissed. Corcoran fired Rosario-Hernandez, and the board eliminated the DEI office ze led. Rufo vows to replace it with a department of “Equality, Merit, and Colorblindness.” Once in place, the now unemployed Rosario-Hernandez anticipates that effort will make New College more hostile to people from marginalized communities.

In late April, the trustees denied tenure to five members of the faculty, prompting their representative on the board to quit on the spot. Amid the changes, universities outside of Florida are actively recruiting the college’s students. Administrators hope that adding intercollegiate athletics will attract a new kind of student. In the meantime, “our enrollment numbers continue to climb,” the college’s communications department said in an email, “and we anticipate having a record breaking enrollment for Fall 2023.”

“If New College fails,” Aaron Hillegass, director of the school’s applied data science program, says, “Christopher Rufo should shoulder a lot of the blame.” Hillegass, who is also an alum and former tech CEO, recently withdrew a $600,000 pledge to the college and submitted his resignation. He fears more professors and students will follow his exit; indeed Sharf plans to transfer later this year. Such losses are a win for Rufo, who told Politico his greatest contribution to the board was the “P.R. rollout” of the takeover. “Thank you for your resignation,” he tweeted in response to Hillegass. “Don’t let the door hit you on your way out.”