Open one social media platform and you’re hit with a fake video; open another and you’re hit with bigotry. Open a news article, and you’ll find some victims “killed” but others “dying.” Each account of events in Israel and Palestine seems to rely on different facts. What’s clear is that misinformation, hate speech, and factual distortions are running rampant.

How do we vet what we see in such a landscape? I spoke to experts across the field of media, politics, tech, and communications about information networks around Israel’s war in Gaza. This interview, with Bellingcat founder Eliot Higgins, is the fourth in a five-part series that also includes computer scientist Megan Squire, journalist and news analyst Dina Ibrahim, communications and policy scholar Ayse Lokmanoglu, and media researcher Tamara Kharroub.

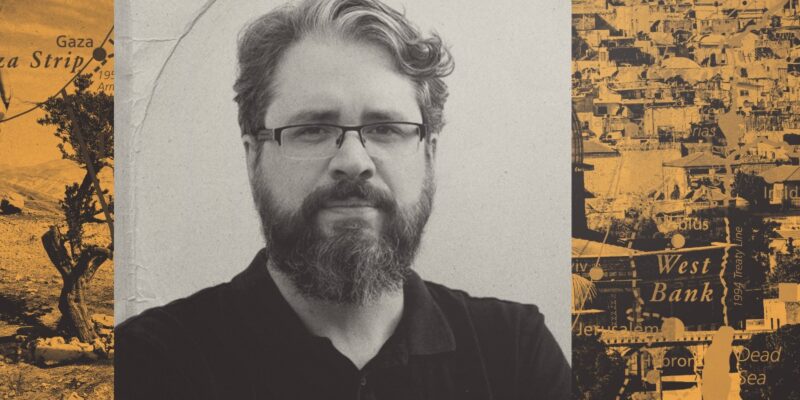

Open-source investigator Eliot Higgins is the founder and creative director of Bellingcat, an independent collective of researchers, investigators, and citizen journalists with a reputation for breaking investigative stories before mainstream competitors. Entirely self-taught, and widely considered a pioneer in open-source intelligence (OSINT), Higgins has transformed the field. An early arms-monitoring collaboration led Human Rights Watch to deem Higgins “among the best out there”; now, more than a decade later, he helps lead some 30 Bellingcat colleagues. We spoke about what open-source intelligence brings to the table, the dangers of rising misinformation, and the October 17 bombing of Gaza’s Al-Ahli Hospital, where rapidly shifting narratives led to widespread confusion about who was culpable.

What’s the significance of OSINT for information being shared about Israel and Palestine?

Over the last few years, there’s been a big shift in the availability of satellite imagery. A few years ago, the quickest people could get it was months out of date. Now, because of services like Planet and Umbra, we can get satellite imagery the next day. We can see an incident being reported, and then have a look at it.

For example, there was the bombing of a large apartment building [in Gaza]. We now have satellite imagery of that same area available, so we can see it remotely. We use it, for example, in Ukraine, where Russia tends to lie a lot about what’s happening.

But Israel is quite open about its bombing campaign. There is not really much debate about if stuff is being bombed. It’s more who’s blowing stuff up and who isn’t. There are very few examples where Israel is saying “We didn’t do that.” Like with the apartment building, they’re saying they blew up the anti-tank rocket commander of Hamas, along with lots of other people.

It only really becomes a point of debate around things like the hospital bombing. That’s more about looking at all the open-source material—the various photographs and videos that have been shared from the scene, and other evidence—and piecing together as much understanding as we can.

The problem has been that a lot of people expect solid answers very, very quickly. Realistically, that’s not possible. This isn’t the kind of conflict where people are happy with uncertainty.

What are the potential dangers of this technology, especially around disinformation? Has it changed from previous conflicts?

When we’ve investigated things like the downing of [civilian flight] MH17 in eastern Ukraine [or] chemical weapons attacks in Syria, you tend to have two different communities that emerge: one side says, “Assad did it,” the other says he didn’t. Communities emerge online and social media discourse develops—some more fact-based, and some more about feelings.

With this conflict, there have been decades of pre-established feelings, understanding, and knowledge. So straight away, with Israel and Palestine, because there’s such heavy engagement, people already have their sights established. They find stuff on social media that supports their viewpoint and re-share it.

What guidance would you give readers who are being flooded with this type of information? What does a well-investigated piece look like?

One issue over the last few weeks is, a lot of organizations that usually produce quite high-quality work on other issues have kind of tried to find answers where there may not be answers available. With the [Al-Ahli] hospital bombing, there are different versions of events, depending on which quite reputable organization you ask, and that’s a problem.

We’ve seen, for example, an analysis by one news organization that pointed towards the rocket being launched from Gaza. Another news organization analyzed the same videos and pointed to it being from Israel. Even good-quality news organizations are producing contradictory statements about the same footage. It’s not even an issue of disinformation around trolls and grifters. It’s a much bigger issue.

You’ve explained that it takes a while to get to the truth. What goes into a Bellingcat investigation?

If we’re talking about conflict incidents, like an airstrike that blows up a building, the first thing we’re trying to do is gather as much of the digital evidence that’s out there, like videos and photographs shared from the scene. Ideally, we try to find them from the original sources where they’re shared, but that’s sometimes not possible.

Once we have all that visual information, we do a process called geolocation, which confirms exactly where these images were taken. You can’t really trust an image from an incident unless you know exactly where it took place. Once you have that, you have a catalog of content of the incident. Then you put that into a timeline.

When you look at footage, you find other images of the same scene, and you start thinking, “What has changed?” You may start looking for munition debris, the shape of a crater, shrapnel spray, and other details like that. Establishing a link between that rocket fire and [an] explosion in the hospital is very important to do.

We also look at media reports and social media posts of witnesses talking about the incident—not to take them at face value, but to look at them and say, “What is consistent with what we’re seeing? What adds bits of information we can explore using visual evidence?” If someone says there was a rocket at the scene, or the remains of a rocket, then we’ll hunt for that through the imagery.

Using that process, [we’re] going back in time to the moment of the event to establish what happened—and, ideally, moments leading up to the event as well. And sometimes that’s possible. For example, we had one investigation into a supermarket hit by a missile in Ukraine. The actual missile in flight was caught by a CCTV camera just outside the building [in] two frames. From that, we’re able to identify the type of missile that was used. It’s piecing together all that evidence, understanding where it is in time and space, and using that nexus of information to start establishing facts and eliminating scenarios.

That’s not to say that if a claim is wrong, the opposite is true. That’s just to say that [the] scenario has been eliminated and we can move to looking at other potential scenarios, hoping that through that process of elimination, you come to one likely scenario—which isn’t always possible.

With the hospital bombing, there was a claim [that] it was a large Israeli bomb. The crater that was left was not from one of those kinds of bombs; it was from a different kind of smaller munition. I personally still don’t know if it was an Israeli missile or rocket or a misfired rocket from Gaza. But I can at least eliminate some of the scenarios. And as more information emerges, you can integrate that into your understanding of the events.

After the investigation, where do you go next?

We use a process that’s focused on legal accountability. That’s the level of analysis that you need of these kinds of conflicts, especially when the mainstream discourse is dominated by people bashing each other over their heads with each other’s claims—where it’s not really about getting to the truth, just making a political point.

There need to be more organizations that are equipped to do this kind of investigative work. We’re doing work on Israel ourselves, but it’s a big, big topic [and] a very rapidly developing situation.

One thing that’s frustrating is that when we’re doing our work in Ukraine, there is, at the end of that, the International Criminal Court and other legal processes that it’s actually moving towards. With Israel, what legal process is it moving towards? Because the US is going to block any UN Security Council resolutions. Israel is not part of the International Criminal Court. There’s nothing that can be done there.

So even if you’re doing good-quality investigations, rather than moving towards legal accountability, it’s just moving back into the same discourse. That is an unfortunate aspect of how the US has approached Israel in the past.

That is not to minimize the damage done by Hamas. You know what they did on October 7.

When you’re dealing with legal accountability, like we do often in our work, there has to be something at the end of that process. And currently, there really isn’t anything present.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.