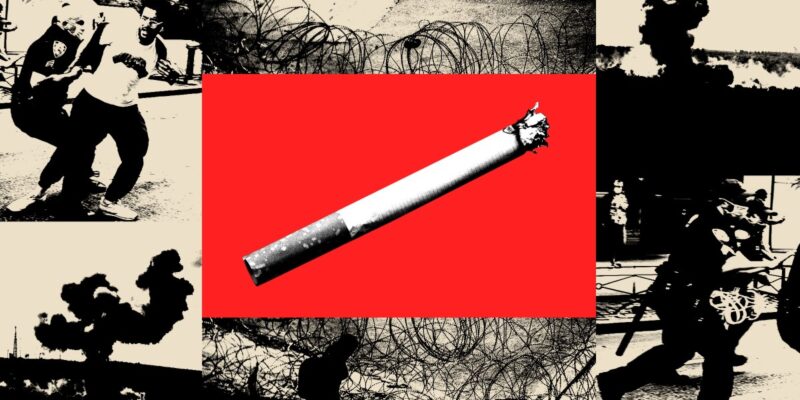

Halfway through the second Republican presidential debate, Fox Business aired an advertisement that made a jarring argument. President Joe Biden’s proposal to ban menthol cigarettes “will fuel an illicit market, lining the pockets of the Mexican cartels,” warned a man identified in the ad as “retired military intelligence.” The spot—which featured images of the desert, the Capitol, Biden, stacks of $100 bills, border fencing, and men carrying a wooden coffin—was attributed to a recently formed group called the “Border Security Alliance.”

Around the same time, radio listeners in 14 large US markets heard ads warning that the menthol ban “could have unintended consequences for African Americans,” who tend to smoke menthol cigarettes. Listeners who want “our communities” to be “protected and not targeted by the police” should call the White House to demand that Biden “halt the ban on menthol,” ads paid for by a group called Alliance for Fair and Equitable Policy stated.

These spots are part of a massive, shadowy lobbying push over the last few years that accelerated as the White House moved toward a goal of finalizing a menthol ban proposed by the US Food and Drug Administration last year. Evidence suggests that much of this effort—involving more than a half dozen organizations across the political spectrum—was funded by Reynolds American, the big tobacco company that earns a major chunk of its revenue from its Newport menthol cigarette brand.

Our border is at a crisis point.

We are battling ruthless cartels on a daily basis.

And now the Biden Administration is considering a ban on menthol cigarettes.

That’s irresponsible.

The President’s ban will fuel an illicit market, lining the pockets of the Mexican cartels. pic.twitter.com/mizkzkylte

— Border Security Alliance (@bsa_us) September 28, 2023

Officials with the Border Security Alliance and the Alliance for Fair and Equitable Policy did not respond to numerous requests for comment. But Reynolds previously has provided funding for a host of other groups involved in the broad campaign opposing the menthol ban, and the corporation has clear ties to AFEP. When Mother Jones asked Reynolds specifically about ads by those two groups, the tobacco giant did not dispute paying for them.

“Like many other companies, Reynolds supports organizations that contribute to the debate on issues that are important to our consumers,” the company said. “Reynolds has been clear on where it stands on this topic—we strongly believe there are more effective ways to deliver tobacco harm reduction than banning products. Banning products often leads to unintended consequences such as the increase of illegal/unregulated products flooding the market.”

This campaign is notable for its ideological flexibility. The groups involved are exploiting existing hot-button issues on the left and right. And it seems to be working. After meetings with lobbyists arguing the ban would unfairly target Black smokers, and amid polling showing Biden’s support from Black voters slipping, the White House recently announced it would delay finalizing the new rule.

The proposed menthol ban grew out of more than a decade of pressure from public health and civil rights groups, like the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, the American Lung Association, and the NAACP, in the wake of the 2009 passage of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. That measure barred the sale of flavored cigarettes, except for menthol, whose fate was left up to the FDA.

According to the FDA, menthol makes kids more likely to start smoking, due to its minty flavor, while also making cigarettes more addictive and harder to quit by enhancing nicotine’s effect. Proponents of the ban argue that eliminating menthol would save lives. They point to a 2022 study that projected up to 654,000 deaths within 40 years could be prevented due to fewer people taking up smoking and others quitting. Because 85 percent of Black smokers prefer menthols, they comprise a big share of the estimated lives saved—255,000, according to the study. However, critics of the proposed ban have focused largely on the potential unintended consequences of the rule.

The Border Security Alliance was incorporated as a nonprofit organization in Arizona on April 29, 2022—one day after the FDA proposed its initial rule banning menthol cigarettes. The group, composed of former law enforcement officials, says that it “promotes social welfare by advocating for public policies to secure the northern and southern borders, support border patrol and law enforcement, combat human trafficking, drug smuggling, illicit tobacco trade, and protect local communities.”

Since May, in press releases, op-eds, and media appearances by its officials, the group has focused almost exclusively on tobacco. The group has urged the administration to step up policing of “illegal foreign-made, disposable vaping products,” from Mexico and China, arguing they target children. That position aligns with that of tobacco companies, eager to restrict competition to their legal offerings in the growing vape market. At the same time, the group has argued the menthol restrictions would create an illicit market for criminals.

Following Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel, the Border Security Alliance updated its message to include terrorists. “The border crisis and violence overseas” make prohibiting menthol cigarettes “a grave threat to our security,” an ad from the group that ran on Fox News last month asserted. “This reckless policy would enrich cartels and terror groups,” it says.

The group spent at least $340,00 on this ad campaign. The debate spot cost the Border Security Alliance $200,000, according to Mitchell West, who leads campaign media analysis for Vivvix CMAG, an ad-tracking firm. Border Security Alliance also spent $30,000 to run the ad the same day on MSNBC and $33,156 to air it the next day on Fox News. The group spent about $78,000 to run the anti-ban ad nationally on Fox News last month, West said.

After initially agreeing to speak to Mother Jones, the Border Security Alliance’s president and spokesman, Jobe Dickinson, did not respond to numerous inquiries. Other officials with the group also declined to respond to basic questions, including about the sources group’s funding.

The group’s arguments have been echoed by several members of Congress.

“FDA must examine the potential effect of such actions to empower Mexican [cartels] and other criminal elements to exploit black markets for tobacco products,” Bill Cassidy (R.La.), the top Republican on the Senate’s health committee, plus Sens. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and two colleagues told the agency in July. In a November 15 tweet thread, Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) claimed the menthol rule would create an opportunity for “Mexican cartels and Hezbollah.”

“Given Hezbollah’s established cigarette business and its ties to the Mexican drug cartels, we cannot discount the potential for this FDA-proposed rule to open a massive revenue stream for this Hamas-allied foreign terrorist organization,” Reps. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY) and Jared Moskowitz (D-Fla.) wrote in a November 14 letter to Biden.

Such claims rely on dubious premises. The senators’ suggestion that cartels may enter the menthol business rests largely on a single May 2022 article from a Mexican newspaper, Milenio, which reported that Mexico’s Jalisco cartel was involved in sales of generic illicit cigarettes within Mexico. The senators’ letter also says that “law enforcement officials” have warned a menthol prohibition “would create a black market.” A footnote attributes that claim to public comments by the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE), a group that until recently listed Reynolds as a supporter on its website. (NOBLE’s website currently mentions Altria, the parent company of Philip Morris, as a sponsor. NOBLE didn’t respond to questions.)

The claim that there is a connection between US cigarette sales and Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed Lebanese group the United States has designated a terrorist organization, has little documentation to support it. An ATF investigation in the 1990s resulted in the conviction of three Lebanese brothers for using proceeds from illegal cigarette sales in the United States to provide material support to Hezbollah. In 2013, 16 Palestinian men were arrested for participating in a cigarette smuggling ring between Virginia and New York. Announcing the arrests, Ray Kelly, then New York’s police commissioner, asserted that “similar schemes have been used in the past to help fund organizations like Hamas and Hezbollah.” The Palestinians, however, were not charged with supporting terror groups. Nor were they accused of importing cigarettes from abroad. Moskowitz and Garbarino’s letter nevertheless cites an article touting Kelly’s initial claim to state: “There have been cases in which Hezbollah and Hamas cells have smuggled cigarettes into the United States to send the revenue overseas.”

A spokesperson for Rubio, whose campaign and PAC received nearly $15,000 from Reynolds’ PAC in 2021 and 2022, said his position was not influenced by the tobacco industry and that its financial backing was a reflection of its support for his existing agenda. A spokesperson for Cassidy, who received $2,500 from the company’s PAC in 2017, said the “insinuation” the senator was repeating tobacco industry talking points is false. “Addressing the use of counterfeit and illicit trade of tobacco (and other products) by drug cartels and terrorist organizations has been a longtime, bipartisan priority of Senator Cassidy,” the spokesperson said.

Spokespersons for Cotton, whose campaign received $1,000 from Reynolds’ PAC on November 10, and for Moskowitz and Garbarino, did not respond to requests for comment.

The Alliance for Fair and Equitable Policy’s arguments were aimed at different groups of Americans. The approximately $300,000 the group spent on radio ads in 14 major markets include at least seven similar ads explicitly aimed at Black listeners. The ads say the Biden administration is “targeting African Americans’” and argue a ban could “increase crime in our communities.”

The group also aired an ad in November on the Ezra Klein Show, a popular New York Times podcast, in a spot seemingly tweaked to appeal to the publication’s affluent, liberal-leaning audience. “The Biden administration is proposing a federal ban on menthol cigarettes that could disproportionately impact Black and brown communities,” that ad says. “If implemented, the ban could fuel an illicit market leading to increases in police interactions and incarcerations.”

The group was formed in Virginia on April 28, 2021—the same day news of the FDA’s plan to ban menthol cigarettes broke. The Alliance is registered with the IRS as a social welfare organization, and in its most recent available IRS filing, covering 2021, the organization said all its revenue that year came from one place: Neighborhood Forward, a St. Louis-based nonprofit, and one with several ties to Reynolds. Its board includes Ingrid Hutt, who has previously registered in California as a lobbyist for Reynolds to “promote the unintended consequences of the menthol ban in the African-American communities.”

Neil Holmes, the Alliance for Fair and Equitable Policy’s president, says on LinkedIn that he has worked for Hutt’s lobbying firm since 2015. Holmes helped Neighborhood Forward organize a 2020 rally against a menthol ban in California. At another rally against the state’s ban, that group promised to pay protestors “$80 for 2½ – 3 hours” of picketing, the Los Angeles Times reported. Hutt and Holmes didn’t respond to inquiries.

The tobacco industry has a long and well-documented history of targeting Black communities dating back to at least the 1950s. Through television ads, billboards, and cultural events, tobacco companies branded menthol as a specialty product and created what Phil Gardiner, co-chair of the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council, calls the “African Americanization” of menthol cigarettes. “When other organizations were not reaching out to Blacks,” says Keith Wailoo, a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University and author of Pushing Cool: Big Tobacco, Racial Marketing, and the Untold Story of the Menthol Cigarette, tobacco companies made “it seem as if they were on the side of minorities, supporting culture, music, fashion shows, and so on.”

Over the years, tobacco companies have courted and funded numerous Black-led organizations, publications, and influential Black political and civil rights leaders. “The industry has long used strategies exactly like this, by which I mean supporting or creating groups to defend markets and employing what you might call mouthpiece organizations to do its work for it,” Wailoo says.

Reverend Al Sharpton’s National Action Network has received funding from Reynolds American for two decades and has lobbied against menthol bans. “I think there is an Eric Garner concern here,” Sharpton told the New York Times, referring to the 2014 killing of the 43-year-old man in Staten Island while he was selling loose cigarettes. Many public health advocates reject that argument. “The concept that what happened to Eric Garner has anything to do with this ban—that getting rid of the sale of menthol cigarettes would somehow give license to the policing community to continue its assault on the Black community—is so irrationally connected that it angers me,” says Cheryl Calhoun, who chairs the board of directors of the American Lung Association.

At an August gathering at the National Press Club in Washington, DC, a coalition of Black law enforcement groups held a panel discussion titled “When Good People Write Bad Policy” that took aim at the ban. “Why would a regulatory body, the FDA, put forth a regulation that will have [a] disparaging and disproportionate impact on our communities based on race?” Benjamin Chavis, the panel’s moderator, asked during the event. Chavis leads the National Newspaper Publishers Association, a trade group for Black-owned community newspapers. (Mother Jones reached out to the National Newspaper Publishers Association but did not receive a response.) Reynolds was a sponsor of the group’s annual conference this year and has also previously reported giving Chavis’ group $225,000 in 2017 and $250,000 two years earlier. The company also provides funds for Chavis’ show The Chavis Chronicles on PBS.

Another speaker at the August event was Major Neil Franklin, a spokesperson for the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP), an organization that in 2019 reported a $450,000 contribution from Reynolds, one-third of its revenue that year. “Illicit markets breed violence,” Franklin said, adding that cartels would take advantage of the “unregulated competition” fostered by a ban on menthol cigarettes.

Franklin told Mother Jones that taking money from big tobacco did not make his group an industry mouthpiece. “Just like any other donor, when they learn of an organization that is doing something that they like, they donate money, and that’s what they did for us,” he said. “If they want to continue to donate money to us, that’s fine. But it will not influence how we speak about this issue.”

Leaders of other Black groups have spoken explicitly about funding offers from Reynolds they have declined. Rev. Horace Sheffield, for instance, a prominent Detroit activist and pastor of New Destiny Christian Fellowship told the Bureau of Investigative Journalism last year that he had been offered hundreds of thousands of dollars from Reynolds to campaign against the ban. He had previously written an opinion piece in the Detroit Free Press calling to “end the deadly hold of menthol cigarettes” on Black Americans. “I was told that some local people had gotten that much money and I could probably get more,” Rev. Sheffield said of an offer of between $200,000 and $250,000 from someone who identified themselves as working for Reynolds.

In August, 32 of 58 members of the Congressional Black Caucus signed a letter urging the FDA to implement the ban. Groups like the Center for Black Health and Equity say there’s no evidence to support the claim that the policy would worsen the over-policing of Black communities. But as the White House deliberated over the rule, administration heavyweights have appeared increasingly sensitive to the arguments that the menthol ban is racist.

On November 20, Chavis, representatives from NOBLE, and Sharpton’s group joined with top tobacco lobbyists—including former Democratic Reps. Kendrick Meek from Florida and North Carolina’s G.K. Butterfield—to press their case in a meeting with high-level officials. Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, White House adviser Neera Tanden, FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, and regulatory czar Richard Revesz were all present for the session. Meanwhile, major public health organizations like the American Cancer Society’s lobbying arm and the American Lung Association had failed to obtain a White House audience to argue in favor of the ban.

White House records indicate that industry advocates—including tobacco lobbyists and convenience and gas store owners worried about reduced sales—have secured 65 meetings with Revesz’s influential White Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs over the menthol rule. Public health groups had six meetings with that office in the same period.

Regarding this disparity, an administration official said: “As is standard practice for all rules, OIRA works to schedule meetings with all requesters while the rule is under review. OIRA does not approve attendees.”

“What an audience the tobacco companies and their allies got,” said Erika Sward, assistant vice president of national advocacy for the American Lung Association. “It’s deeply troubling that they have the ability to capture such an audience when many of the groups from the public health community have yet to get a meeting at all.”

The White House now says it hopes to finalize the menthol rule by March. But supporters of the regulation fear—and opponents hope—the administration is poised to punt until at least after next year’s election. “The FDA remains committed to issuing the tobacco product standards for menthol in cigarettes and characterizing flavors in cigars as expeditiously as possible; these rules have been submitted to OMB for review, which is the final step in the rulemaking process,” the agency said in a statement. “At this stage in rulemaking, the FDA is limited from further discussions about the rules before they are published.”

Corey Pegues, Neighborhood Forward Board member and vocal critic of the menthol rule, said he expected the White House would delay the ban further. “They don’t want to take Black people’s Newports away from them before the election,” Pegues said. “They’ll lose.” Pegues, a former New York police officer, said he receives consulting and speaking fees from Reynolds. But he said those funds don’t influence him. “Money could never take my integrity or honesty,” he said. “If someone is definitely getting paid to say they are opposed or for it, that’s one thing. But if someone is getting paid because they have a strong opinion, it is what it is. That’s just the American way.”