Frustrated by the two-party system? Polling shows you’re not alone, with more Americans than ever supporting the idea of a third party. But the winner of November’s presidential election will be either Biden or Trump, and voters weighing other candidates need to consider if a protest vote to end the duopoly might instead help end our democracy. In the May+June 2024 issue, we examine the past and present of third-party outsiders, and how they could upend this year’s race. You can read all the pieces here.

Voters love to complain about the two-party system, which can leave us feeling stuck: Trump and Biden again? Yet most of our elections rely on a process that guarantees frustration. Plurality voting—pick one candidate and the top vote-getter wins—usually makes supporting third parties untenable, leaves vast swaths of the electorate emotionally disenfranchised, and allows a rich, bigoted reality TV star to split the primary vote, ooze on into a general election, and win with far fewer votes than his opponent. But even putting the Electoral College aside, voting experts broadly consider plurality the least fair system in use, says William Poundstone, whose 2008 book, Gaming the Vote, describes superior methods devised over the centuries by mathematicians, political scientists, and reformers. While some are widely used, each has its pros and cons—and the wonky details matter.

Plurality

The process we know and loathe: Pick one, and the person with the most votes wins.

Pros: Easy to understand and tabulate.

Cons: Limits opportunities for third parties, flattens nuance in voter preference, results in polarization, and maximizes dissatisfaction. Favors incumbents and candidates with big bankrolls. Candidates can prevail with less than a majority. Donald Trump won South Carolina’s 2016 GOP primary with just 33 percent—and got all 50 delegates.

Where used: 50-plus nations, from Azerbaijan to the US—but nowhere in the EU.

Two-Round (Runoff)

Plurality, but with a runoff if nobody exceeds a threshold (typically 50 percent).

Pros: Helps temper third-party “spoiler” effect.

Cons: Drawn-out process still favors major parties.

Where used: Executive elections in most of Europe, 12 US states (Mississippi, Georgia, and Louisiana use it in general elections for federal offices), and lots of cities.

Borda Count

In this method, devised by Jean-Charles de Borda circa 1770, voters rank candidates by preference. In a four-way race, a first-choice vote typically gets four points, a second pick gets three, and so on down. Points are tallied and high score wins.

Pros: If voters mark their true preferences, Borda produces fairer outcomes than plurality.

Cons: A candidate preferred by the majority can lose. It’s also highly gameable: “Borda basically said, ‘My system is intended for honest men,’” Poundstone told me.

Where used: College football’s Heisman Trophy and other “most valuable player” contests, Kiribati, Nauru.

Condorcet

In this family of voting methods, named for mathematician Nicolas de Condorcet, voters again rank candidates in order of preference. The rankings are used to see how each candidate fares against each rival candidate in a head-to-head matchup. The Condorcet winner is the one who beats every other contender.

Pros: “Almost universally regarded as the most fair, representative, and accurate way to tally ranked choice ballots for single winner elections,” notes the Equal Vote Coalition.

Cons: Administration can be a challenge. The “Condorcet Paradox,” a scenario in which A beats B, B beats C, and C beats A, requires a convoluted tiebreaker that voters may have a hard time understanding.

Where used: Washington’s Libertarian Party, the Pirate Party of Sweden, and nongovernment entities ranging from MTV to the Wikimedia Foundation.

Instant Runoff Voting (Ranked Choice)

Voters also rank candidates in this system, implemented by American architect William Robert Ware circa 1870 and championed by the nonprofit FairVote. If anyone gets over 50 percent of first-choice votes, they win. If not, the contender with the fewest is disqualified, and the second-choice votes of their supporters are distributed among the survivors—this continues until a majority winner emerges.

Pros: Discourages negative campaigning, as candidates vie for rivals’ second-choice votes. “It works quite well” in races with two formidable frontrunners, Poundstone says, dampening the spoiler effect.

Cons: Races with multiple strong contenders can get weird. In the 2009 mayoral contest in Burlington, Vermont, IRV eliminated the clear Condorcet winner, who would have bested any rival head-to-head.

Where used: Alaska, Maine, and many cities, including New York, San Francisco, and Seattle; also Australia, India, and some UK elections.

Total Vote Runoff (Baldwin’s Method)

An older method revised in 2022 by Ohio State election law expert Edward “Ned” Foley and Harvard economist Eric Maskin, TVR promises to eliminate instant runoff misfires by using all votes, not just first choices, to determine which candidate is eliminated first. With TVR, Foley has shown, mainstream Republican Nick Begich would have crushed Sarah Palin in the first round of Alaska’s 2022 special House election and gone on to beat Democrat Mary Peltola. (The election was run under ranked choice, and Begich was eliminated first, allowing Peltola to beat Palin.)

Pros: Delivers high voter satisfaction in multicandidate races, and the Condorcet winner always prevails; TVR is “ultimately just one of the Condorcet methods,” notes computer scientist and voting expert Rob LeGrand.

Cons: The post-vote math is harder to understand than IRV. Captures less voter nuance than range/score methods (see below).

Where used: Nowhere yet. A 2024 ballot measure would enable it in Arizona.

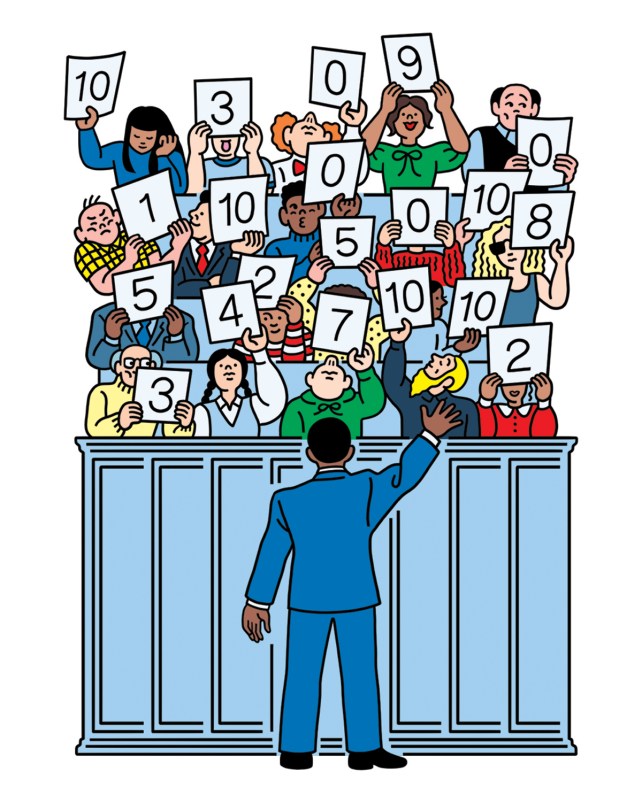

Range Voting

Picture Olympic judges rating gymnasts zero to 10. Voters score candidates on a numerical scale. Add up the points, and you’ve got a winner.

Pros: Intuitive, captures granular preferences, and may discourage negative campaigning even better than ranked choice. Mathematician Warren D. Smith, a key proponent of range voting, claims it results in about 2 to 10 times less voter regret than plurality voting.

Cons: Untested in modern political settings and encourages strategic voting. (To boost your favorite candidate, you could give all others a zero.) Also pretty subjective: As Foley points out, your “5” and mine could mean very different things.

Where used: Ancient Sparta used a crude version wherein candidates were paraded one by one before a crowd of eligible shouters. Whoever got the loudest support, as scored by evaluators listening out of sight, won. Today it’s mostly found in online product rankings.

STAR (Score, Then Automatic Runoff)

A hybrid of range voting and instant runoff. Voters scale candidates from zero (worst) to 5 (best). Of the two candidates with the highest average scores, the one rated higher by the most voters wins.

Pros: Easy to understand, captures voter nuance, helps address range voting’s gameability problem, and a Condorcet loser can never win.

Cons: Untested in politics. It’s also conceivable, notes the League of Women Voters, for “the candidate the most voters would prefer” to be eliminated in the first round.

Where used: A ballot initiative this May could bring STAR voting to Eugene, Oregon. Organizers there also hope to get a referendum on the statewide ballot in November.

Approval Voting

People can cast votes for—i.e., approve of—as many candidates as they like. The person with the most votes wins.

Pros: Simple, eliminates spoilers and vote-splitting, and disfavors extremist candidates. It also, according to NYU political scientist Steve Brams, increases turnout, discourages negative campaigning, and is “less manipulable than any nonranked voting system.”

Cons: Less nuanced than range voting—and “some of its beautiful properties disappear,” LeGrand says, when you use it in races with more than one winner—say, for a local commission with two open seats.

Where used: Fargo and St. Louis; professional mathematics and engineering societies; and UN secretary-general elections. Also used for centuries to elect popes—and the doge in Renaissance Venice. “Apparently it worked pretty well there,” Poundstone says.

Proportional Representation

PR systems are not voting methods, but rather electoral structures meant to allocate power in a more representative way. Winner-takes-all elections produce just one victor, locking out voters who favor other candidates. In a proportional system, though, if one-third of voters back a party, it will typically get about a third of the seats. PR is widely used in parliamentary nations, and you can see the difference even in US presidential elections, where 48 of 50 states award all of their Electoral College votes to the state’s plurality winner, whereas partisan convention delegates in most state primaries are allocated based on each candidate’s share of the vote.

Pros: Undercuts gerrymandering while boosting new parties, political inclusion, civic participation, and coalition lawmaking.

Cons: Factionalism can result in party bloat, making it hard for voters to track which party stands for what. Requires large, multiseat districts (currently against the law) for state and national legislative elections, which can take a toll on local accountability and constituent services.

Where used: Brazil, South Africa, Germany, Spain, and many other European nations. Rep. Don Beyer (D-Va.) has repeatedly introduced the Fair Representation Act, which would bring a state-by-state version to Congress.

Fair share

Here’s how the 2016 election would have gone had states assigned electors by each candidate’s percentage of the vote.

- Hillary Clinton: 268

- Donald Trump: 267

- Gary Johnson: 2

- Evan McMullin: 1

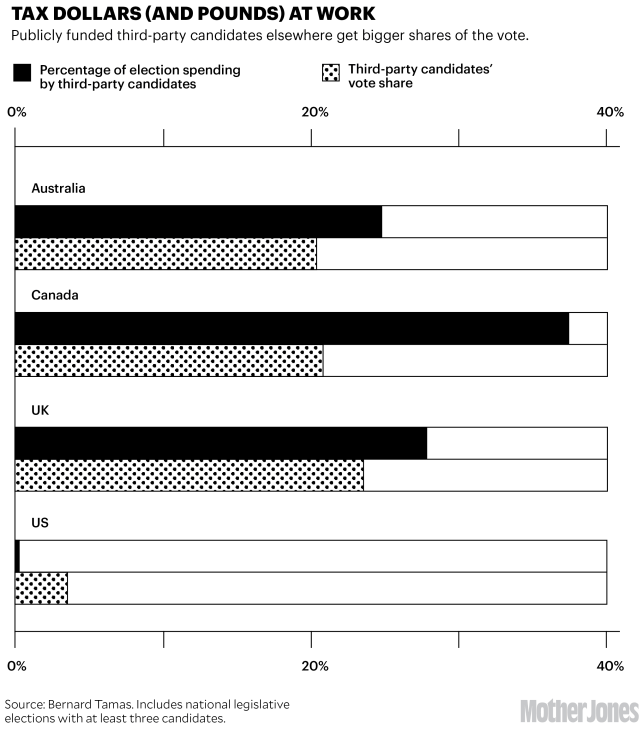

Public Financing

If the United States’ winner-takes-all elections are a big barrier to third parties, so are our expensive and privately funded campaigns. While 70 percent of countries provide direct public funding to political parties, the US’s system for doing so is moribund—and when it operated it was almost entirely restricted to Democrats and Republicans.

America’s status quo empowers monied interests, who naturally see out-of-power third parties as “bad investments,” says political scientist Bernard Tamas. Other countries with similar political traditions and single-member electoral districts—like Australia, Canada, and the UK—level the playing field via generous public financing or free television time and mailings, and regularly elect third-party members to their national legislatures. It could happen here: Maine’s pioneering campaign-grant system is not only popular with lawmakers in both major parties, it’s also helped independents and a Green Party legislator win seats. —Clint Hendler