Ya Li is a slight, soft-spoken accountant who was born in China and now lives with her husband and daughter in Australia. But from 2017 until last year, Li was also known as Mulan, a top member of an international “whistleblower movement” with the stated goal of supplanting China’s Communist Party as the country’s legitimate government.

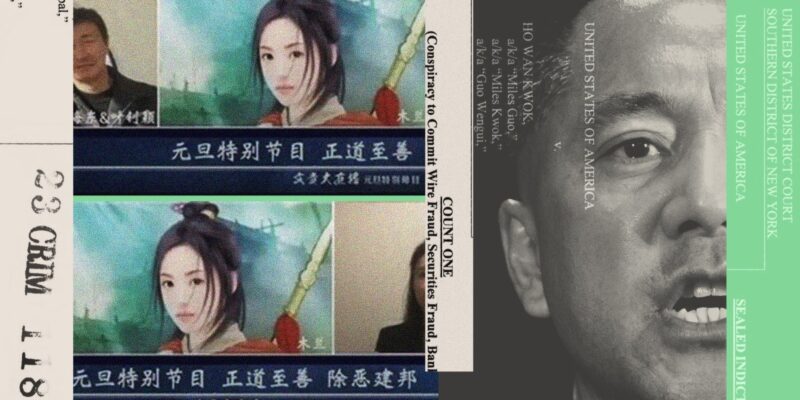

While preparing taxes for individuals and small businesses by day, Li worked as a director of the Rule of Law Foundation, a nonprofit that was launched by fugitive Chinese mogul Guo Wengui and Steve Bannon and that Guo had claimed he would donate $100 million to. Li, on paper, became the head of an well-endowed investment fund and a director of a British Virgin Islands corporation, wiring tens of millions of dollars between accounts in Dubai and New York.

“It’s a scam.”

Li did all of this while keeping details of her life, and her face, a secret from Guo and her so-called her “fellow fighters” in his movement. Instead, she used an avatar of Disney’s Mulan, a character based on a Chinese legend of a girl who disguises herself as a man to fight invaders.

Li’s two identities came together last Wednesday when she walked into a courtroom on the 26th floor of a federal building in Manhattan. She was there to testify against Guo, who faces racketeering, fraud, and money laundering charges for allegedly stealing hundreds of millions of dollars from supporters he’d persuaded to invest in his various business ventures.

Li entered the courtroom escorted by two federal agents. She had signed a non-prosecution agreement under which the US Attorney’s office agreed not to charge her for any crimes she may have committed while working for Guo, as long she testifies truthfully.

Her appearance caused murmurs of dismay in a courtroom packed with Guo supporters. Though three other witnesses who were part of Guo’s movement had testified earlier in the trial, Guo lawyers emphasized they had few direct dealings with Guo. Mulan, Guo’s fans knew, was a bigger fish, a top lieutenant whose importance Guo had touted in broadcasts.

Li had worked for Guo ceaselessly from 2017—when she first joined his movement after learning about him on YouTube—until last year. But their daily interactions were all remote. She had never encountered him in real life before testifying against him in open court.

On the stand, Li looked terrified. She averted her eyes from her former boss, who stared intently at her. Li was unsure whether to sit down after she was sworn-in, and she spoke so quietly that the judge and lawyers told her dozens of times to speak up. A person who spoke to Li before the trial said Li had feared that she might faint when saw Guo.

Guo had claimed he would “never use supporters’ money buy anything, even a meal,” Li recounted.

In her testimony, Li outlined a story that is illustrative of Guo’s strange and hard-to-categorize movement. It is both political—publicly its aims to “take down” the Chinese Communist Party—and financial. Guo assured followers they would get rich by investing with him. Made up of tens of thousands of Chinese emigres spread around the world, Guo’s movement is also linked to the US far right.

Like many Guo fans, Li began following Guo in 2017, as his supposed revelations about Chinese corruption drew a furious reaction from the Chinese government, including unsuccessful and illegal lobbying to win his extradition from the United States. Those efforts proved a publicity boon for Guo.

Li joined an online group of followers, what Guo would later call a “farm.” In 2020, as Guo began urging fans to invest in his businesses, Li, like thousands of others, gave her time and money to the effort. She even liquidated a retirement fund to raise cash to invest.

Like other investors, she got burned. She says he lost $20,000 in Guo’s schemes. “It’s a scam,” she testified last week.

Li rose in Guo’s organization because she was able to do translation and bookkeeping—and because she was a hard worker who was, she said, unquestioningly loyal, unusually ardent even among what critics call a cult-like movement. “We trust him hundred percent,” Li said. “No doubt, no question.”

Li said that Guo called her “Sister Mulan.” He told followers, “We are brothers and sisters,” she explained. “We like a big family.”

Guo put Li in charge of a team of translators in Australia that eventually grew to more than 100. He gave her sensitive tasks, including translating legal documents and messages for his lawyers. And he made her responsible for collecting money that supporters in Australia wanted to invest in an online streaming company, GTV, and other projects he launched over the next few years.

Li testified that on Guo’s direct instructions, she wired funds not to companies Guo’s fans believed they were investing in, but to other entities Guo personally controlled. Prosecutors have offered evidence that Guo used money in those accounts to buy luxury cars, a mansion, and other goods.

At Guo’s behest in October 2020, Li wired $2 million she had collected from Guo’s fans in Australia to a US company she had never heard of, she testified. A year later, a Guo lawyer pressed her to sign a promissory note claiming the money had gone to a different company, which Li had also never heard of, let alone sent money to. But she complied, she said, out of loyalty to Guo.

Around the same time, Li also played a small role in US politics. Bannon, who had obtained a copy of Hunter Biden’s hard drive, arranged for Guo to spread sexually explicit material from the laptop, as I reported in 2022. Guo in turn tasked Li and another top supporter with posting material from the laptop online, along with captions and, in many cases, false claims about the material. Fearing lawsuits, Guo ordered Li to post material first outside the US. None of this has come up during Guo’s trial. And Li declined to talk to me about it. But WhatsApp messages I obtained show that Guo gave Li and the other follower detailed instructions on how to distribute the material, and they complied. Guo, who other witnesses have described as a harsh taskmaster, also occasionally berated his underlings. “You guys are stupid” he told them in one WhatsApp message.

Li continued to serve Guo as other top supporters left of were ousted from his movement. She stayed on even after his March 2023 arrest.

But she told jurors that she began to have doubts after learning new details about Guo’s 2021 purchase of a $26 million mansion in Mahwah, New Jersey. Federal prosecutors revealed that Guo had bought the home with investor funds Li had helped raise. Rather than dispute this, Guo followers claimed he had purchased the residence as a “base” for his movement. But Li knew otherwise. She had personally helped transcribe and translate an audio message from Guo to a lawyer detailing his plans to buy the house as a residence for his family, she testified .

Guo had claimed he would “never use supporters’ money buy anything, even a meal,” Li recounted. But, she said, that was a lie—told to investors who wanted their money used “for taking down the CCP, not for his family members or for his personal luxury life.”

Li’s breaking point came later in 2023, she told jurors. Guo had previously filed for bankruptcy, a process that requires a US trustee, appointed by the court, to represent the interests of creditors. That meant locating assets Guo controlled, including funds he had transferred to offshore accounts in an apparent effort to prevent creditors from finding them.

By the spring of 2023, the trustee was moving to seize $38 million in funds stashed in the Guo company in the British Virgin Islands. That company had two directors. One was Guo’s top assistant, Yvette Wang, who had been arrested and jailed along with him. (She pleaded guilty last month.) The other was Li, who said she took the title on Guo’s instruction in 2022.

Li said she heard nothing about the company until after Guo’s arrest, when Guo supporters sought her help transferring the funds. Li testified that a lawyer working for Guo named Zhang Youngbing pressed her to sign an affidavit stating that the company was legitimate and that she had previously authorized a transfer of the funds at issue.

“He lied to us.”

Li said the affidavit was false. She knew nothing about the company and had not okayed any transfer of funds. She declined to sign, she said, “because I know we can’t say [a] lie to the court.”

Zhang responded by threatening her, Li testified. He told her she would be “fully responsible” for paying back the money to Guo if it was seized, she recalled. She said she understood Zhang also meant she would be banished from the movement.

Li said this choice— between committing alleged fraud on Guo’s behalf or facing retaliation from the movement she’d devoted her life to—caused her reconsider her seven years of all-out toil for Guo, work she had prioritized so much that “I didn’t look after my family.”

Li concluded Guo’s movement was a fraud. “We’d been cheated by Miles Guo,” she testified last week. “He lied to us.”

“I feel very angry, desperate,” she continued. “I feel guilty. I feel regret, and I’m very depressed, and I thought—thought about suicide.” Li testified that she decided against ending her life “because [of] my daughter.”

The courtroom was largely silent for this testimony. But behind me, one Guo supporter told another: “She’s a good actress.”

Zhang, the lawyer Li named, was also present in the courtroom during some of her testimony, wearing a blue tailored suit similar to the one Guo wore that day. But as Li named him, Zhang quickly left the room.

I caught up to him later in an overflow room elsewhere in the courthouse. “What she testified was false,” he said. Declining to respond to specific questions, he repeated that sentence several times.

On cross-examination, Sabrina Shroff, one of Guo’s defense lawyers, aggressively questioned Li’s claims and suggested she had taken money put up by Guo investors as management fees. Li denied personally receiving fees. She appeared distressed under cross-examination, though, repeatedly pausing for long periods—for more than a minute in one case—before answering.

Li had testified that her parents in China had been visited by CCP security officers due to her online activities. Shroff, referencing Guo’s claim to be a top CCP enemy, asked if Li was testifying to win favor with Chinese authorities. “The only way you can safely go back to China is if you disavow your relationship with Mr. Miles Guo, correct?” the attorney asked.

At this, Li bristled. “I come here and I show my face,” she said. “Even now after [I] testify, because I show my face, I’m even in greater risk [from] the CCP.”

It was not clear how jurors reacted to this exchange. But Guo fans looked pleased. As Li left the courtroom after three days on the stand, some chuckled. Others stared angrily at her. Guo smiled widely.

Li, again accompanied by federal agents, departed with her eyes cast downward. She had testified that she planned to return immediately to Australia.

The next witness was the head of a luxury car dealership in Houston who in 2021 sold a $4.4 million Bugatti to a Guo company. The car was allegedly bought with investor funds raised by Guo followers, including by Li, who Guo had called a “sister.” According to prosecutors, it was one of several luxury vehicles Guo bought for a member of his real-life family, his son Guo Qiang.

Update, June 14: This story has been updated to include details relating to Hunter Biden’s laptop.