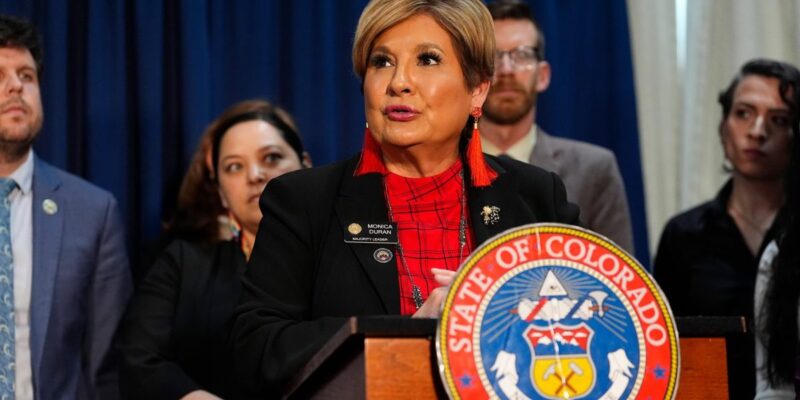

When Monica Duran, the Democratic majority leader in Colorado’s House of Representatives, was 19 years old, she escaped domestic abuse with her young son and did what many survivors try to do: She fled to a shelter and sought counseling.

“For so long, you hear that you are worthless,” Duran told me. The support she received after leaving, she said, helped her realize that “I was worthy, I did have something to offer.”

As intimate partner violence continues to rise, such services are critical for helping survivors of domestic and sexual violence heal. But as I learned during my recent investigation for Mother Jones, they are becoming increasingly difficult to access due to a yearslong decline in federal funding from a pot of money created by the Victims of Crime Act, or VOCA. Colorado is not exempt. The state went from getting $31.3 million in VOCA funds in fiscal year 2017 to about $13.6 million in the most recent fiscal year, when the money was stretched to help support more than 125,000 survivors—mostly women who were victims of domestic violence or sexual assault, Department of Justice data shows.

Like most states, Colorado has tried to stave off the worst effects of the funding cuts, with state lawmakers allocating millions of dollars to affected programs. But those providers are still struggling after years of plummeting federal funding. Roshan Kalantar, executive director of Violence Free Colorado, the statewide domestic violence coalition, said some have had to close office space and eliminate legal advocacy services, which help survivors file for divorce or obtain emergency protective orders against abusers. More could soon follow. “We have at least two programs that might close,” Kalantar told me last week, “but many more will essentially limit what they can do.”

Duran and Kalantar are trying to avoid those outcomes. They are among the forces behind a ballot measure that, if passed by voters next month, would create a new funding stream for victims’ services in the state by imposing a 6.5 percent excise tax on firearms and ammunition as of next April, when it would take effect. The measure, known as Proposition KK, would create an estimated $39 million in annual revenue, the bulk of which—$30 million—would support VOCA-funded services for victims of crime, as well as crime prevention programs in Colorado. The rest of the funds would go toward mental health services for veterans and young people and increasing security in Colorado public schools. The bill that proposed the ballot measure passed in the Colorado General Assembly in May, with most Democrats supporting it and most Republicans in opposition. Should voters support the measure, the tax would not apply to firearms vendors that make less than $20,000 annually, law enforcement agencies, or active-duty military personnel.

Supporters—including Democratic Gov. Jared Polis, the National Network to End Domestic Violence, and Everytown for Gun Safety—say Prop KK would bolster desperately needed services in the state and could serve as a model for other states trying to come up with innovative ways to respond to federal VOCA cuts. Accessing support after intimate partner violence, Duran said, “is a matter of life and death—this is how serious this is.”

The tax on firearms has resulted in strenuous opposition from the gun lobby. The National Rifle Association’s Institute for Legislative Action, the organization’s lobbying arm, said earlier this year that the proposal “should be seen as nothing more than an attack on the Second Amendment and those who exercise their rights under it” and pointed to a similar measure in California, which imposed an 11 percent excise tax on firearms and ammunition earlier this year and has faced a court challenge for being unconstitutional.

Several Colorado pro-gun groups—including the NRA state chapter, the Colorado State Shooting Association; Rocky Mountain Gun Owners; and Rally for Our Rights—have also opposed Prop KK, noting that firearms and ammunition are already taxed at 11 percent on the federal level. Ian Escalante, executive director of Rocky Mountain Gun Owners, said in a video posted to X: “This is the radical anti-gun left trying to punish gun owners for exercising their rights.” Spokespeople for the three state-level groups did not return requests for comment from Mother Jones.

Duran, who said she’s a gun owner, said she’s “disappointed that this has been turned into a Second Amendment issue,” especially because domestic violence and the shortage of resources to support survivors is “a crisis.” Kalantar sees the tax on guns and ammunition in Prop KK as fitting, given the role that firearms often play in intimate partner violence. Research has shown that more than half of domestic violence homicides involve a gun and that access to a firearm makes that outcome more likely. Last year, there were 58 domestic violence fatalities in Colorado, more than three-quarters of which were caused by guns, according to data released this month by the state attorney general’s office. “It feels very appropriate that people making money off the sale of guns in Colorado should participate in the healing” of survivors, Kalantar said.

“It feels very appropriate that people making money off the sale of guns in Colorado should participate in the healing” of survivors.

If the measure passes, the Blue Bench, a sexual assault prevention and support center in Denver that served about 7,000 survivors last year, is one of the organizations that would benefit from this new source of revenue. Executive Director Megan Carvajal says VOCA funds make up half of its budget, paying for counselors who lead therapy sessions for survivors, the 24-hour hotline they can call in a crisis, and case managers who offer support at hospitals and police stations in the aftermath of assaults. In June, Carvajal learned that the Blue Bench’s latest VOCA award would be less than $650,000—a 40 percent cut compared with the previous year’s budget—which will mean laying off three therapists, two case managers, and a community educator who visits schools to talk about informed consent and healthy relationships. The organization will also have to move out of its Denver office space by the end of the year and transition to being mostly remote, Carvajal said.

If Prop KK does not pass and organizations like the Blue Bench face even further funding cuts, Carvajal’s prediction is grim: “People are going to die.” Research suggests that more than 30 percent of women contemplate suicide after being raped and more than 10 percent attempt it. More than half of all suicides involve a firearm, and suicides by firearm are highest in states with the fewest gun laws, according to a KFF analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. For Carvajal, the work she and other advocates do is essential to reduce those statistics—but is only possible with adequate funding.

“If you pick up the phone and someone says, ‘I believe you,’” Carvajal said, “it can change your mindset from wanting to die to wanting to live.”

If you or someone you care about is experiencing or at risk of domestic violence, contact the National Domestic Violence Hotline by texting “start” to 88788, calling 800-799-SAFE (7233), or going to thehotline.org. The Department of Health and Human Services has also compiled a list of organizations by state.

If you or someone you care about may be at risk of suicide, contact the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988, or go to 988lifeline.org.