Journalism, especially investigative journalism, has never been an easy task. However, in the age of disinformation, growing public distrust of the work of the press — fueled by the rise of the far right around the world — has contributed to the spread of attacks on journalists and media outlets. This is especially true during times when emotions are at their most heated, such as elections.

And 2024 was an especially challenging year for Portuguese-speaking journalists, with voters in three Portuguese-speaking countries across three continents — Portugal, Brazil, and Mozambique — going to the polls.

In Brazil, according to the Coalition in Defense of Journalism, which monitored social media during the country’s municipal elections, “the analyses reveal patterns of aggression that threaten the practice of journalism in the country and the fundamental role of the media as a watchdog of public power.” On X (formerly Twitter) alone, there were 35,876 attacks. Outside the digital environment, the report recorded 11 cases of physical or verbal violence against journalists.

In Portugal, which celebrated the 50th anniversary of the end of the military dictatorship this year, the rise of the far right risks reopening wounds. According to Reporters Without Borders, although Portugal rose two places in its World Press Freedom Index and is now the 7th-highest ranked country in the world, journalists have been threatened or attacked — physically or verbally — by people linked to the far-right Chega party, which came third in this year’s polls.

For our Portuguese Editor’s Pick this year, we chose pieces that stood out — whether for their innovative format, their reach and impact, or relevance to the public interest of the topic covered.

Brazil — Brazilian Institute Produced Poison for Chilean Dictatorship to Assassinate Opponents

In 2024, Brazil marked 60 years since the coup d’état that established the military dictatorship. To mark the milestone, GIJN member Agência Pública published a series of stories that “reveal how there is still much to be investigated about the long years in which the military and civilian alliance took away our democracy.” In one of the reports, the outlet detailed how one of the most renowned scientific institutes in Brazil — Butantan — was involved in the persecution of scientists considered “communists,” and uncovered the organization’s strong ties to Chile during the reign of dictator Augusto Pinochet. According to the investigation, which took six months, Butantan’s headquarters was once visited by a delegation of high-ranking officials linked to Pinochet and, in 2008, a scientist found boxes with vials of botulinum toxins from the Butantan Institute in the basement of the Chilean Public Health Institute — enough to “exterminate half of Santiago.” Agência Pública obtained previously unpublished documents and testimonies that indicate that the toxins produced in Brazil were used to poison political prisoners opposed to the Chilean dictator’s regime – and that the renowned poet and diplomat Pablo Neruda, winner of the 1971 Nobel Prize for Literature, may have been one of the victims.

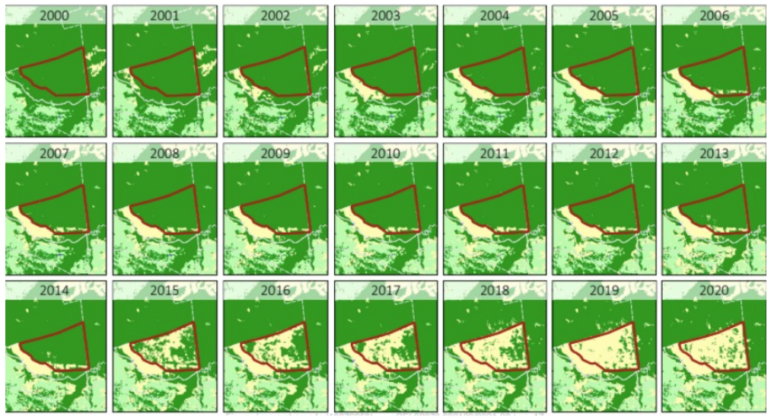

Brazil — Deforestation in Search of a Culprit

Deforestation in a country like Brazil, where the Amazon alone covers around half of the territory, is a serious concern. But how can the government combat environmental crime without knowing who is responsible? This report from piauí magazine dove into the problem and found that, even though the government has a mechanism to stop deforestation in problem areas by “embargoing” the zone, the rules are of limited effectiveness when the culprit remains unidentified. According to the report, almost 1,400 areas in Brazil have been embargoed for environmental violations since 2009 without the culprit being identified by the government — costing the state millions of dollars in lost revenues.

The embargo rules allow the government to curb abuse by forcing offenders to stop any activities causing deforestation, requiring the offenders to pay fines, and even limiting their bank credit. With the support of the Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA), piauí cross-referenced thousands of records from the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (or ICMBio, the agency responsible for managing and protecting federal conservation units) with different land databases, embargo maps, and documents obtained through right-to-information requests. The reporters also tracked down some of the landowners whose identities were supposedly unknown. In response to the investigation, ICMBio has committed to reviewing the cases.

Brazil — Army Spends Millions Every Year on Pensions for ‘Fictitious Dead’

Image: Screenshot, Folha de São Paulo

Folha de São Paulo revealed that the Brazilian Army spends more than R$20 million (approximately US$3.2 million) per year on pension payments for the families of the so-called “fictitious dead” — military personnel expelled from the force for having committed crimes or serious infractions. According to this investigation, there are currently 238 military personnel, including 38 officers, in this group. According to Brazilian law, despite their convictions, military personnel do not lose the right to a military pension. However, since they cannot receive these payments directly due to their circumstances, they are classified as “dead” administratively, to allow their pensions to be paid to family members. This is the first time that this data has been made public. It was obtained through the country’s Access to Information Law and provided to Folha by Fiquem Sabendo, a nonprofit and GIJN member that specializes in public transparency. Last year, the agency had collated data on the pensions of “fictitious dead” members of the Navy and Air Force.

Portugal — The Big ‘Family’ of Chega

“The people are in charge, not the elites that govern us”: this is one of the mantras that has served Portugal’s far-right Chega party since it was formed in 2019. But according to this investigation from Público, the party has seen its support surge across social strata, and even counts members of the “elite” among its backers.

The report is an unprecedented portrait of a party that achieved the third-largest number of parliamentary seats in the country’s legislative elections in 2024. The report showed how the populist radical right has attracted the sympathy of various layers of society, presenting the stories of dozens of donors. The panorama is of a party that is managing to appeal to a diverse mix: business people related to the real estate sector or the sale of weapons and military equipment, members of the nation’s aristocracy; and those who sympathized with Portugal’s former dictator, including one person implicated in an attempted coup. At the other end of the spectrum are people who donated a few hundred euros, such as market vendors, car washers, and even Brazilian immigrants and people with left-wing family heritage. All were contacted by the reporter and many gave their versions of why they identify with the party’s cause — the vast majority cited the “fight against socialism” and a wish for stricter immigration laws.

Brazil — Investigating How a Court Verdict Impacted Neighborhoods ‘Sinking’ in Maceió

Since 2018, thousands of residents have had to leave their homes in Maceió, the capital of the northeastern Brazilian state of Alagoas, as parts of the city started to sink. The problem — which has led to five neighborhoods being completely evacuated — is attributed to the impact of four decades of mining for rock salt extraction, and the consequent collapse of the mines. In this report, The Intercept Brasil dives into how a 2019 court ruling favored the mining company, even after the sinking of the neighborhoods was confirmed.

The outlet accessed the full text from the presiding judge, and consulted a public defender in the case, who suggested public agencies “had to give in” to an agreement since a legal process of this magnitude could take many years and the families would remain in the area at risk. Although measures were taken to assist the victims, according to the report, the agreement did not recognize the company’s responsibility for the environmental disaster and even granted it possession of the properties of the compensated residents.

Brazil — Porto Alegre Did Not Invest in Flood Prevention in 2023

In Brazil’s southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul, the month of May saw heavy rains that caused widespread flooding and left hundreds of cities submerged — of the state’s 497 municipalities, 467 were affected, according to authorities. There were 183 deaths, 27 missing, and more than 500,000 people were left homeless. The region’s largest airport, in the state capital of Porto Alegre, only resumed full operations months later, in December. Rio Grande do Sul is no stranger to flooding, but according to this investigation by the news portal UOL, in 2023 the Porto Alegre city government did not invest any money at all in flood prevention. According to the report, the city’s budget has an item called “improvement in the flood prevention system,” which has seen sharp drops in funding in recent years before finally being zeroed out, even though the water and sewage division has significant reserves at its disposal. The data – taken from the city’s Transparency Portal – also revealed that staffing in the water and sewage team has been reduced by almost half since 2013.. When contacted, city officials did not deny that flood prevention improvements was left out of the 2023 budget, but stated that there were expenses in flood prevention in other areas, such as mapping risk areas, renovation of pump houses, and purchase of boats.

Brazil — The Evolution of Rural Militias in Southeastern Pará

Image: Shutterstock

A team from Repórter Brasil, a GIJN member, traveled more than 6,000 kilometers to investigate the connection between the violent land evictions and “Bolsonarism” — the right wing movement revolving around the country’s controversial former president. The resulting special report featured interviews and analysis of thousands of documents, in addition to a trip through the states of Pará and Mato Grosso. In one of the reports, the team explained how in the southern parts of Pará, settlers live in fear of illegal evictions carried out by landowners and backed by heavily armed militias. According to the team, the government of former President Jair Bolsonaro made it easier to carry and own weapons — with a 212% increase in firearm registration between 2017 and 2022 in Pará alone. Together with his aides and supporters, he also “encouraged rural violence” and openly criticized landless movements, the reporters said. Although Bolsonaro was defeated in the 2022 elections, the practice of hiring gunmen and forming militias to remove families remains, according to this report. But one thing has changed: the violent modus operandi. If before the leaders of landless rural workers were murdered, now, the strategy is to destroy everything, but without killing, so as not to leave martyrs.

Brazil — 61 Candidates Run for Election with Outstanding Arrest Warrants

This year, elections were held to elect mayors and city council members in thousands of cities in Brazil. But after one sharp-eyed reader reported a candidate was on the run for a rape allegation, two journalists from the G1 news portal decided to investigate whether there were other candidates with similarly troubling histories. They cross-referenced national data from more than 300,000 arrest warrants with the information on more than 460,000 candidate registrations — and discovered that 61 people running for office had outstanding arrest warrants. Most of the cases were for debts related to non-payment of alimony, but there were also more serious alleged offenses, such as robbery, theft, fraud, and even homicide. The reporters had the help of other journalists from G1, which has local teams spread throughout the country, to find and interview all the candidates and their parties. Brazilian law does not bar candidates who have outstanding arrest warrants from running, only those who have been definitively convicted. However, candidates could still be arrested during the campaign. In a remarkable sign of instant impact, according to the Federal Police, 36 of the fugitive candidates were quickly arrested.