Recent reports suggest roughly one million people have been killed since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. At least 107 of them were current or former media workers, 18 of whom were killed while reporting, according to the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues to present unprecedented challenges for Ukrainian journalists and media. In addition to being at constant risk of physical danger from Russian air raids, one-third of Ukrainian journalists have reported facing pressure and threats — in particular from the Ukrainian government institutions — according to the Media Development Foundation’s annual survey. These threats include surveillance by law enforcement agencies, online harassment campaigns, offline intimidation, and an attempt to deliver a military summons to a journalist in retaliation for exposing corrupt officials.

Add to these challenges severe economic difficulties; staff shortages as many journalists have been mobilized or have volunteered to fight; war-related power and internet outages; restricted access to public information; and difficulty getting responses to FOIA requests as officials cite martial law. Despite these threats and challenges, Ukrainian journalists continue to uncover corruption and other misdeeds, potential war crimes, and even attacks against themselves and their newsrooms.

‘We Found Them’

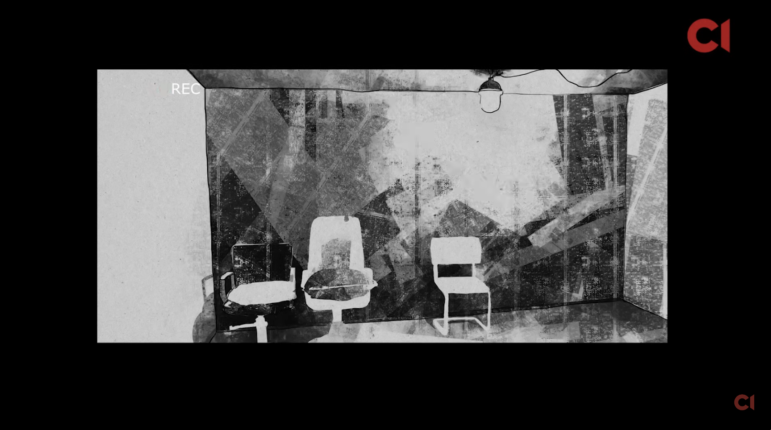

After broadcasting a series of investigative reports uncovering high-level corruption in government contracts for reconstruction in Ukraine, journalists from GIJN member Bihus.Info became the target of an online campaign seeking to discredit their team. Compromising information, including phone call records and video footage from hidden cameras, appeared on a little-known website called Narodna Pravda — where staff portraits of its purported editors and journalists were AI-generated. After analyzing excerpts of published phone conversations and videos, Bihus.Info journalists discovered that they had been followed and surveilled for roughly a year — and that hidden cameras had been installed at a hotel where they held training sessions and a New Year’s Eve celebration. Using videos from outdoor surveillance cameras in that hotel, a facial recognition service, crowdsourcing by readers, and an application with caller ID features, Bihus.Info journalists identified 30 secret service agents who may have spied on journalists and installed hidden cameras in their bedrooms and saunas.

How Poland Trades with Russia via Belarus

Ukrainska Pravda’s (UP) investigative journalist Mykhailo Tkach revealed how thousands of Polish trucks hauling Russian agricultural products entered Poland through Belarus — avoiding sanctions — while Poland had prohibited imports of the same products from Ukraine after mass protests by Polish farmers objecting to cheap grain imports from Ukraine blocked the Ukrainian-Polish border.

UP journalists inspected both borders, talked to Polish experts and colleagues, verified information from sources with the Import Genius and ComTrade databases, and identified at least three Polish companies that may have been increasing trade with Russia. For additional verification, journalists placed phone calls to companies to offer Russian products on behalf of a real Belarusian company. The UP journalists reported that during this investigation, Polish police detained and searched them for several hours on the street, without an interpreter present or being allowed to call lawyers. According to UP’s statement, police also confiscated the journalists’ camera memory cards.

In late November, UP’s Tkach published another investigation on bypassing sanctions, in which he showed how a shadow fleet helps Russia sell oil. He not only tracked ships using Marine Traffic but also filmed them with a drone, and he divulged how the tankers registered in offshore jurisdictions ship Russian oil off the coast of Bulgaria and Romania, and how this oil has been then unloaded at the governmental oil refinery terminal in Bulgaria. (The video is available with English subtitles.)

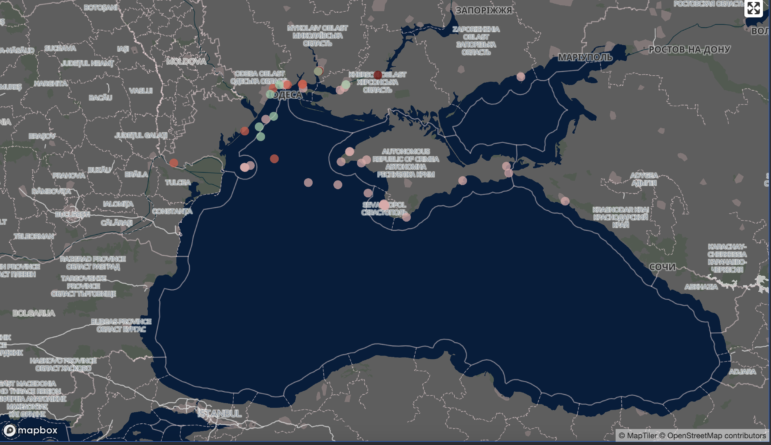

Damage to the Black Sea Caused by War

As part of a cross-border project with journalists from Bulgaria, Georgia, Moldova, Romania, and Turkey, Nikcenter — located in Mykolaiv in southern Ukraine — documented the environmental consequences of Russia’s war in Ukraine, particularly the hostilities’ effects on the ecology of the Black Sea. With the help of satellite images, open data, scientists’ research, and testimonies of local residents, journalists reported on the death of fish and dolphins, numerous fires on the Kinburn Spit (part of the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve and where Russian ammunition depots are located), oil spills, the destruction of dams, and the chemical and organic pollution of water and shores. Nikcenter notes that researchers are documenting what Ukrainian environmental scientists have termed “ecocide” — intentional damage to the natural environment — to use as evidence, potentially in future international court proceedings, that Russia was deliberately causing ecological disasters as a weapon of war.

Sexualized Violence as a Weapon of War

This Slidstvo.Info documentary tells the stories of four Ukrainian men who experienced sexual violence and torture when they were held in camps during Russia’s occupation of Kherson, a port city on the Black Sea. A priest, an IT specialist, a cafe owner, and a former policeman, what their stories have in common is their brutal treatment — various types of violence, in many cases sexualized, beatings, and torture with water and electric current. The Slidsvo.Info team collected victims’ statements and witness testimonies, and with open source tools tried to identify those involved in torturing the detainees.

Other investigative media have also investigated sexualized violence as a weapon of war. In their documentary “He Came Again”, the Kyiv Independent told the stories of victims and identified the potential perpetrators, and also tried to trace the commanders who potentially knew about the violence but did not stop it or punish those involved.

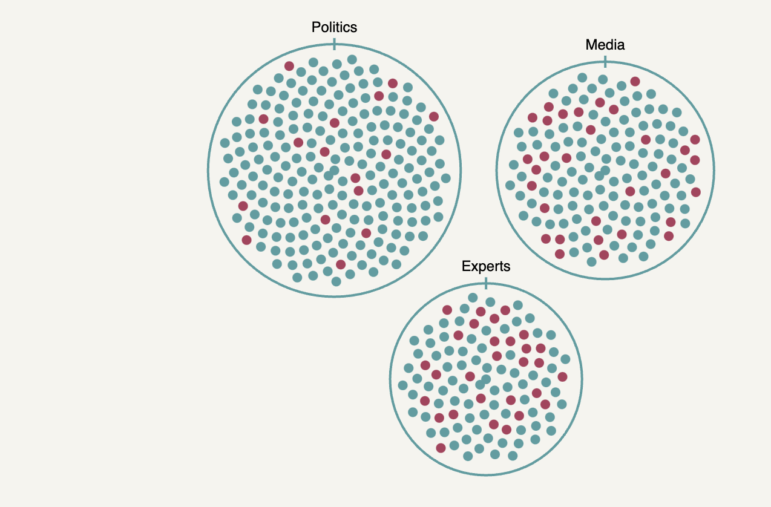

Roller Coaster: Analyzing US Support for Ukraine

Based on an analysis of several thousand pieces of content mentioning Ukraine in the US starting from February 24, 2022, data newsroom Texty compiled a list of organizations, influencers, and politicians who oppose support for Ukraine. The Texty team found that these individuals’ arguments often lined up with common narratives found in Russian disinformation and propaganda, including historical myths predating the war. After publishing the study, Texty reported that they faced pressure and threats of physical violence and a “wave of hate” on social media, including proposals to deprive them of funding and demands to add Texty to a list of “terrorist organizations.”

The Quality of Ukrainian Army Food

This investigation was sparked when a Ukrainian army officer told NGL.media about the poor food quality his battalion and other frontline units endure; journalists verified his claims by interviewing other military personnel, conducting experiments, and analyzing the contents of canned goods given to the armed forces. NGL.media concluded that at least one Ministry of Defense-related laboratory — tasked with checking food for compliance with state standards — approved the delivery of almost 11,000 cans of stewed pork unfit for consumption. According to the journalists, these cans contained tendons, skin, and fatty tissue instead of meat. The Ministry of Defense did not address or respond to the investigation. Still, nine days after it was published, the Ministry of Defense terminated a two billion hryvnias (US$48 million) contract with the food suppliers, increased fines for similar violations, and approved new inspection procedures.

Ukrainian Children Recruited to Set Fire to Armed Forces Vehicles

Schemes, the investigative program of Radio Free Europe’s Ukrainian service, analyzed call records and correspondence — obtained from sources — of Ukrainian teenagers who had been offered money to set fire to cars belonging to Ukrainian military personnel. The journalists interviewed many teenagers who had been detained for arson and wrote to several “recruiters’’ on Telegram — who were offering substantial sums for minors to set fire to soldiers’ cars and film it — and were able to trace how the recruiters were connected to Russia’s special services. The aim was to create a disinformation campaign, casting these arson incidents as evidence of a protest movement in Ukraine.

After the investigation was published, hundreds of organizations, including government buildings, schools, business centers, hotels, newsrooms, and embassies throughout Ukraine received threatening letters stating that mines had been placed in their offices, prompting large evacuations. The letters also falsely claimed that the RFE/RL journalists who worked on the car arson investigation were responsible for mining the buildings.

Shadows Across the River

Reporters from the English-language Ukrainian outlet Kyiv Independent looked into the experiences of civilians in the Russian-occupied left bank of Ukraine’s Kherson region, to uncover and document potential war crimes. With access to occupied territory nearly impossible for journalists, law enforcement, and agencies alike, the usual newsgathering and open source methods were ineffective, and the team had difficulty persuading witnesses to talk, as people in occupied territories avoid posting on social media or speaking publicly for fear of being prosecuted or punished. But after a trip to the frontline in southern Ukraine, the reporters managed to talk to dozens of people who had fled from the occupied region and establish the names of several victims who were tortured or killed for pro-Ukrainian views. They were also able to identify Russian police officers and other persons allegedly involved in committing crimes.