It started with a grieving mother’s story. Near the town of Matsapha in central Eswatini, the small southern African kingdom formerly known as Swaziland, Zodwa Nkambule’s daughter was attacked and raped so violently that she had been left unable to walk and required frequent hospital visits, and later died. The man accused of the crime was arrested, but then released, and died without facing charges.

This is just one of many tragic stories. An investigation into systemic violence against women in Eswatini by the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ), titled Without Justice: How Eswatini’s System Is Failing Victims of Gender-Based Violence, observes that — in a six-month period — “[T]he word ‘rape’ appear[ed] in the Times of Eswatini almost every week” and that rates of rape incidents in the country are above the international average — and yet still underreported.

Nkambule’s account was the initial spark for what later became a large-scale investigation that — instead of reporting on individual incidents or perpetrators — focused on the systemic factors and institutions that enable sexual assault and violence against women in Eswatini, and how the justice system fails victims. By finding, collecting, and analyzing court data, reporters turned a single personal story into an evidence-based investigation for a systematic problem that had long been discussed, but the true extent of which had remained opaque.

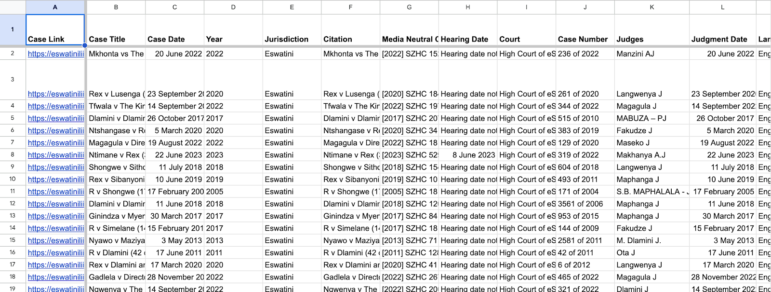

A team from the CCIJ — which supports investigative reporting around the world through mentorship and editorial resources — reviewed patterns of crime reporting in the Times of Eswatini; interviewed activists campaigning for change and a woman affected directly by such crimes; examined three years of data collected by the nonprofit Swaziland Action Group Against Abuse (SWAGAA); and analyzed more than 4,600 high court cases from 1977 to the present, finding more than 330 cases relating to crimes connected with gender-based violence, of which 253 were rape charges.

“Our investigation reveals a series of gaps where victims fall through the cracks during the accountability process,” they write — a pattern they say indicates a justice system “overwhelmed by the volume of cases under the new law,” referring to the Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence Act (SODV) adopted in 2018 to crack down on the prevalence of such crimes.

These gaps include:

- Victims are too afraid to report their experiences or pressured to withdraw their accounts.

- Cases disappearing from court rosters or being dismissed for procedural errors.

- Judges misapply the law or cases drag on for years.

Below, then-CCIJ series editor Carolyn Thompson and data editor Sotiris Sideris share a 10-step guide to understanding how their team found the right data, established a methodology for interpreting it, and was able to expose a systematic failure of justice.

CCIJ series editor Carolyn Thompson (center) with data editor Sotiris Sideris (right) and CCIJ Africa Editor Ajibola Amzat at iMEdDIJF24. Image: Courtesy of Thompson

1. Start with a Focused Hypothesis

The investigation started with a simple assumption: “We like to use the framing: ‘Someone is doing something for a reason,’” Thompson explains. In their case, they hypothesized that the Eswatini government neglected to prevent cases of sexual violence by failing to enforce relevant laws, including SODV, and by not making the population aware of the issue. To prove this assumption, they needed to identify points to prove it.

2. Gather information: What Do You Know So Far?

At the start of an investigation, gather all the pieces of evidence that you already know and collect them in a guiding document. According to NGOs such as Human Rights Watch and UNFPA, more than one-third of women in Eswatini will have experienced some form of sexual violence before turning 18. The CCIJ team then considered what information they needed to prove this, and why cases might not result in successful convictions.

3. Build an Information Map

To find the most useful information for your investigation, you need to figure out where to look. “Think about the hypothesis,” Thompson advises. “Where would information be gathered, and where would it live?”

Information connected to crimes of sexual violence, for example, could be medical records, police reports, mental health support data, or even social media, where people might share their experiences. However, it’s important to select the sources of information that have been collected wisely. “Our goal isn’t to then go gather everything on the list,” Thompson adds. “Our goal is to think through the many places where potential data might exist, and then decide what could help contextualize the report.”

4. Find Data Sources

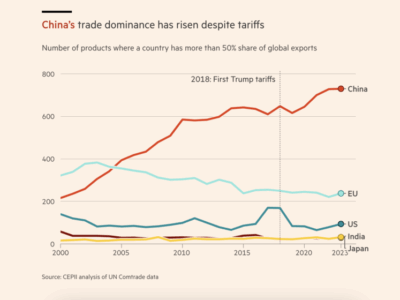

There are several methods to find the data sources you need. The simplest way is to search for information online. In this case, the team uses a simple tailored online search looking for the file type (PDF) and “eswatini” as well as the word “court.”

“We were lucky because we found a public database of the Swatini supreme court,” Sideris says. However, this might not always be the case. Other ways of finding a data source could be web scraping for public data, accessing closed data by paying for it, gathering information and creating your own data, filing a FOIA request, or simply talking to experts to request the information.

Google search for filetype:pdf, Eswatini, and court. Image: Screenshot, Courtesy of CCIJ

5. Analyze, Sort, and Extract the Data

After finding a public database with millions of entries, the reporters needed to find a way to analyze which data contained the most useful information for their investigation. They decided to filter the data based on keywords such as “rape” or “sexual assault” and used web-scraping to get access to the data. However, Sideris advises against this manual selection process “because we found out later there was an API we could have asked for.”

Instead, look for any kind of program or AI that can help scrape the data. After scraping, the team created a spreadsheet adding some relevant information, such as the date of the case. For inaccessible files, the team used Amazon Textract to be able to add document text to their dataset.

Scraping the data, Image: Screenshot, Courtesy of CCIJ

6. Assess the Data

To be able to assess the data without getting lost, you need to go back to the hypothesis and think about what you are trying to prove. What is your hypothesis, and in what way can the data help answer these questions?

“Identify the data to be collected and build a methodology to be consistent,” says Sideris. The team did so by combining simple data points with interpretative assessment, such as whether the case is a sentencing or not. “The ideal way is to build clear data and add a layer of interpretation to it by combining the results, with the aim of answering your investigative questions,” Thompson adds. You can do this automatically in the spreadsheet if the data is simple (such as using the date format), manually if the data is interpretative or use AI, which is much faster, if the data is semi-interpretative.

7. Build a Methodology

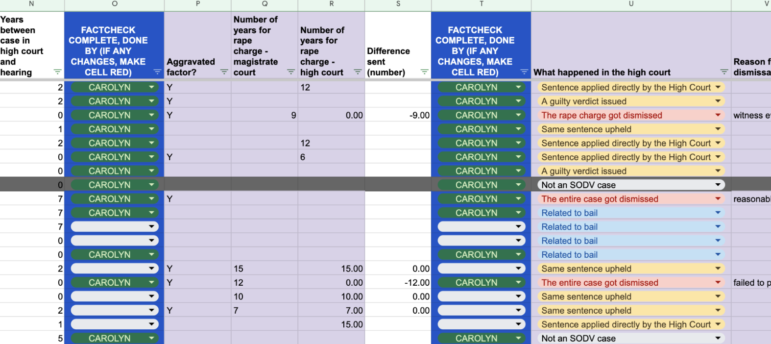

The team decided to use Chat GPT-4 to interpret the data. To do so, they needed to write a detailed prompt that gave clear instructions on what the AI should do.

“A methodology helps in three ways,” Sideris explains. “It means everyone is aligned so all data is filled in the same way, it can be published so others can review your methods and choices and it can be fed into an AI tool to ensure it understands what you want.” But he also stresses that the thought process should still be made by the journalist: “Use AI and automation as a research tool or filter, not for interpretation.”

Chat GPT-4 prompt and methodology details in the gallery below.

8. Check Your Methods with Experts During Reporting — And Prior to Publication

Remember, we are journalists, not data scientists. It’s always useful to work with an expert to double-check your methodology. As Thompson notes, these experts will know important context you might miss, whether similar research exists, be able to spot patterns, and — most importantly — be able to tell if you are oversimplifying or misinterpreting any data.

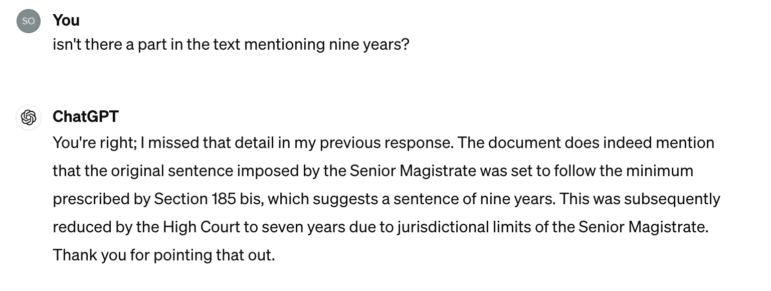

9. Manually Check the Data

“If you use automation or AI, never publish results without manual confirmation,” warns Thompson. Journalists should never fully trust AI, and always double-check for any mistakes or missed data points. “If you use an AI tool, ask it to prove what it found to facilitate your fact-checking,” Thompson says. “Sometimes manual fact-checking is the best way.” In their investigation, they found several details Chat-GPT4 had missed. None of them changed their findings, but identifying the AI errors helped to make their story stronger. “Chat-GPT4 is just a tool,” Sideris adds. “And it will hallucinate [generate a false or misleading response] , miss things, or lack context.”

Double checking Chat GPT-4. Image: Screenshot, Courtesy of CCIJ

Manual checks of data. Image: Screenshot, Courtesy of CCIJ

10. Identify the Story

After you’ve analyzed the data and checked for errors, you can search for the stories your data can tell you. However, you should always self-reflect, and interrogate your own potential biases in interpreting the data, Thompson notes: “Often, your assumptions based on one anecdote are not accurate when you see the pattern.” You can use tags as a filter to understand the data — and, again, ask an expert to help you understand your findings and provide context you might be missing.

In this investigation, the CCIJ team was able to prove how Eswatini courts are systematically failing to deliver justice to victims of sexual violence. The journalists also used a similar methodology to report on stories from Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Ethiopia, where they investigated discrimination against people with dreadlocks, the connection between child marriages and religious affiliation, and cases of weaponized rape involving military cooperation.

A final piece of advice Sideris gives to fellow reporters is to “publish your methods and findings for transparency.” This way, others can use the dataset for further research and cross-check and learn from your investigative techniques.

Editor’s Note: You can find the full dataset here, and digitized court records from several other African countries here.