Reporters can now access and download satellite images good enough to see individual buildings at almost every location on Earth — in minutes, with no special skills, and entirely for free.

Of course, there are still no guarantees that the images you want will be from the exact date you may need, or that they are not obscured by clouds.

But experts say the fact that any reporter, anywhere, can easily grab an image of any place via open source platforms for ever-more story topics represents a game-changer for watchdog journalists, including those in less-resourced newsrooms.

This was one key takeaway from a recent GIJN webinar on “How to Acquire Free Satellite Imagery for Your Investigations,” featuring three expert speakers: Carl Churchill, graphics reporter at The Wall Street Journal, Yao-Hua Law, an award-winning environmental journalist from Malaysia, and Laura Kurtzberg, data visualization specialist and a former applications engineer at a commercial satellite company, Descartes Labs. The webinar itself reflected a vast appetite for satellite access tips among journalists, attracting 616 attendees from 114 countries, making it one of the most popular webinars in GIJN history.

To sum up this new reality, Churchill told attendees: “Most satellite data is free, open, and global.” But a second major takeaway for reporters was the fact that otherwise expensive, extremely high-resolution satellite images produced by commercial providers — those good enough to distinguish an individual car — can also be obtained for free, if you know how to ask.

Experts say there is a misperception among many under-resourced newsrooms that this kind of forensic evidence is limited by exclusivity deals or advanced open source data skills, and that private satellite vendors don’t welcome requests for free data from outlets they don’t know.

“Being with a large US newsroom, people may assume we have a lot of secret, expensive tools to access satellite imagery, but we really don’t,” Churchill explained. “Most of what we use are the exact same tools available to anyone.”

While there are several other good public portals such as NASA WorldView and EO Browser, Kurtzberg explained that just two easy-to-use open source tools — Google Earth Pro and, especially, the recently-launched Copernicus Browser — are all reporters need for most sat image use-cases. (For those familiar with EO Browser, see how it differs from the newer Copernicus Browser at this link.)

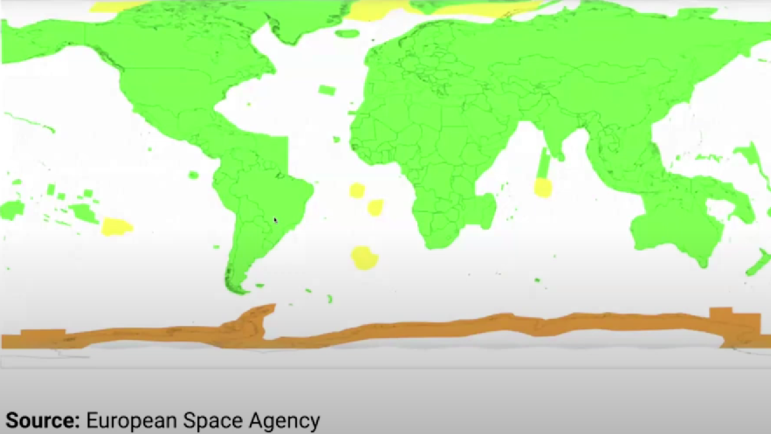

In a map that reveals the global reach of free satellite data, the areas in green (above) are those imaged by the medium to high-resolution Sentinel 2 satellite constellation every five to six days. Image: European Space Agency

Churchill noted that the processed mosaics provided by Google Earth often include very high-resolution imagery that can help reporters understand detailed ground features and changes over time, but that it does not allow direct reporter control over single images.

His presentation focused on the European Space Agency’s Copernicus tool, partly because — unlike Google Earth — Copernicus allows users to download single images.

Using the case study of a shuttered gold mine on the Senegal-Mali border, he showed attendees how:

- Copernicus defaults to the excellent Sentinel 2 satellite constellation, which shows medium-high, 10-meter resolution images, and revisits the same spots — mostly in the local time mornings — every week. You likely won’t need an alternate resource, or any technical knowledge of different satellite capabilities. “Anything at or above 10 meters per pixel is likely to be available for free,” Churchill noted. “That is more than enough quality to distinguish individual buildings and easily enough to look at land development trends.”

- If you click on Copernicus’ cloud icon on the main menu, you’ll find a Max Cloud Coverage slider bar that — remarkably — allows you to immediately see on which days Sentinel imaged that spot at the cloud cover level you prefer, via a digital calendar display. (You can try your luck for any clear days toward the left end of the slider.) You can then click the date and briefly wait for a downloadable image to load.

- Band frequency bars on the menu allow easy visualization options, such as false color.

- Having identified your location by coordinates or a place name, you can simply zoom in — and orient yourself by clicking overlay data such as roads or borders under the Labels tab at the top right.

- Click on the Download icon on Copernicus’ right-hand menu to download images as a JPG file, which will also load the time stamp, attribution, and any labels. Just don’t forget to publish the listed attribution. For a more advanced analysis option, Churchill noted that — provided you first create an account with Copernicus — you can also click the Analytical tab to create a data-rich TIFF file, which you can drop into data software such as QGIS.

Using Satellite Images as a Field Reporting Strategy Tool

While news consumers are used to seeing satellite images most often in stories about war and deforestation, Law emphasised that free satellite imagery offers many other applications for undercovered topics and even reporting strategies.

For instance: reporters headed for unfamiliar locations can easily scout the trip on the Copernicus browser before leaving the office, noting obstacles, field conditions, and unexpected story opportunities, or travel options and potential evacuation routes.

Law offered one example of a forested area he visited in Malaysia that was blank on Google Maps, but that a search using Copernicus revealed pathways, obstacles, and precise distances on satellite.

“I told my local guide: ‘This is what we’ll encounter,’ [during the journey] and he was very surprised that I knew this,” he recalled. “This is very handy for me. If I’m going to some place I’m not familiar with, I will definitely check it out on the satellite image first.”

Other creative applications include:

- Verification of claims. “When a company claims they’ve done something on the ground in a remote area, we can use these images to check if that’s true,” Law explained.

- Measuring slopes on the ground. Copernicus includes a remarkable Elevation Profile feature, where you can draw a line on the image, and it will generate a side-on graph of the terrain slopes along that line. This can also help with topographical analysis, confirming a feature is a sand dune, for instance, rather than a crater.

- Visual tours of large sites. Law used Google Earth and bright hand-drawn lines to show the vast array of businesses and infrastructure that would be affected by a government proposal to create a nature reserve extending 50 meters into either side of a river.

- Tracking land use changes over time. Attendees saw how a 2024 image overlaid on a 2017 image revealed a 15-meter retreat in one Malaysian shoreline, due to coastal erosion.

The Copernicus imagery tool utilizes imagery from the ESA’s Sentinel 2 satellite. Image: Screenshot, ESA

How to Pitch Requests to Commercial Providers

In the rare cases that your investigation needs an image from a specific moment in time, or a clear view of a vehicle-sized object, you’ll likely need a one-meter-or-less resolution photo that typically involves paying a fee. Besides military satellites, those hi-res images are only gathered by commercial vendors like Planet Labs, Maxar Technologies, Airbus Earth Observation, and BlackSky.

In the case of certain major global incidents, however, some firms will voluntarily send journalists their initial batch of free-to-use high-res images of the event. But reporters do need to sign up to those companies’ press lists to receive those image dumps.

In other cases, you’ll need to ask a marketing or communications professional at those firms for a free image – and, having previously held one of those jobs, Kurtzberg urged attendees: “Definitely reach out!”

“It’s worth sending out an email or filling out their contact form, because a lot of the time, companies are very interested in having journalists from small, local, global organizations use their imagery,” she explained. “It helps them get their name out there and look good.”

Kurtzberg recommended that reporters try not to include deeply technical details in their initial requests, such as precise resolution levels or cloud coverage ratios.

“Be polite; describe what you’re hoping to do with that imagery; describe your organization and the amazing project you’ll create; and keep your email short,” she advised. “It’s okay not to be familiar with the technical details. A lot of times the scientists at these organizations will help with that, and with your analysis.”

For more on this topic, see our detailed tips on corporate image requests from Kurtzberg and Washington Post reporter Daniel Wolfe — including useful email addresses and satellite “tasking” — under the “Dealing with Commercial Providers” section in GIJN’s “Tipsheet for Acquiring Free Satellite Images.”

To learn more, you can watch the full GIJN webinar on How to Acquire Free Satellite Imagery for Your Investigations below.