Estrella Santos-Zacaría says there’s one thought that often terrifies her, whether she’s at home, at work or with her friends: being deported to her native country of Guatemala.

“I told my lawyer: ‘You know what I think most? I’d rather die than go back there. I don’t want to leave,’” the transgender woman said in an interview with Noticias Telemundo from Los Angeles, the city where she has lived for the last year and a half.

“In the place where I lived, they don’t accept me,” said Santos-Zacaría, 36.

Santos-Zacaría’s story gained media attention in 2023 when the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled in her favor, giving her another chance to argue that U.S. immigration officials were wrong in rejecting her bid to fight deportation on the grounds she’d face persecution in Guatemala.

Santos-Zacaría has testified in public legal documents that she was raped and threatened with death as a teenager in her native country.

“I was abused, I was raped, and I was only about 12 years old. I never told my family what happened to me, because if I spoke, that boy would kill me or someone in my family. The fear I had left me traumatized, and I said that the best thing to do was to leave,” Santos-Zacaría said.

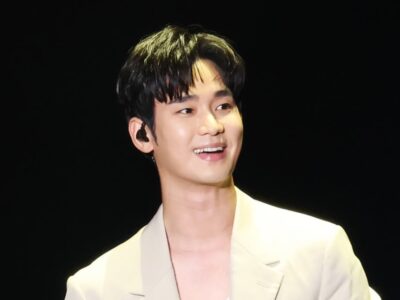

Estrella Santos-Zacaría at her home in Los Angeles on Feb. 13.Telemundo

Now, amid new Trump administration policies restricting immigration, amping up deportations and rescinding some legal pathways for immigrants and asylum-seekers to stay in the U.S., those arguing Santos-Zacaría’s case are worried.

“My fear is that with all the executive orders and political pressure, they will end up changing the asylum laws and measures such as the suspension of deportation, which is what we are fighting for,” said Benjamin Osorio, Santos-Zacaría’s attorney. “That would be terrible because they could expel her.”

Her attorney’s fears persist despite recent legal victories.

On Jan. 13, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that Santos-Zacaría can continue to challenge an order for her deportation, or removal, to Guatemala.

“We won the opportunity to continue fighting to keep her from being deported, but the case is going back to the appeals board and I think she will have to go back to immigration court,” Osorio said.

Despite the last ruling in her favor, President Donald Trump took office on Jan. 20 and his administration has issued a series of executive orders that, among other things, have suspended the government’s refugee program, mandated federal recognition of only two sexes (male and female) based on an “immutable biological classification,” and ended the CBP One application through which many people applied for asylum appointments before entering the U.S.

“It’s clear that their mission is to make it much more difficult to obtain protection,” said Aaron Morris, executive director of Immigration Equality, a nonprofit that advocates for and represents LGBTQ+ people in the immigration system. “And I think asylum, suspension of removal and protection under the Convention Against Torture fall into that agenda.”

Noticias Telemundo contacted U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services for comment on the effects of recent executive orders on immigration processes as well as on the situation for people requesting these protections, but has not received a response. The Executive Office for Immigration Review, the Justice Department office that conducts deportation proceedings, declined to offer comments or an interview on the subject.

After Santos-Zacaría left Guatemala, she fled to Mexico and then crossed into the U.S., but was deported in 2008. Ten years later, she returned to the U.S. — she has said she was attacked in Mexico — and was detained by immigration authorities. Since then, she’s been pleading her case to stay in the U.S., arguing she wouldn’t be safe if she’s deported.

Since Santos-Zacaría had already been deported from the U.S., she was unable to apply for asylum, but did apply for withholding of removal and protection under the Convention Against Torture, or CAT. In the recent Fifth Circuit ruling, the court granted Santos’ request to continue fighting for withholding of removal, though it denied CAT protection.

“It is common for the court not to approve everything while the process continues — the people who request the suspension can have a work permit and can stay in the country,” Osorio said.

“But what is happening now, as we have seen in the news, is that other countries want to accept migrants of other nationalities, and that can be a big problem for these people,” Osorio added, referring to the recent proposal by El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele to accept immigrants from other countries who are deported from the U.S.

Experts consulted by Noticias Telemundo agree that current laws contemplate deportations to third countries, including in cases of deportation suspension and CAT protection, meaning the U.S. government can expel beneficiaries of these measures to a country other than the one where they’re at risk.

In the case of Santos-Zacaría, this would suggest that even if she’s not sent back to Guatemala, she could be expelled to El Salvador or any other country that the authorities consider suitable.

“In general, we have not seen that happen,” said Adriel Orozco, a senior adviser at the American Immigration Council, a nonprofit advocacy organization and think tank. “However, there are always changes in immigration policy.”

The prospect of deportation to another country worries Santos-Zacaría, and several experts agree there is reason to worry.

“We know that Brazil is the No. 1 country in terms of violence against trans women and Mexico is the second-most violent country, but it is a problem throughout Latin America,” says Bamby Salcedo, president of the TransLatin@ Coalition, a nonprofit that focuses on the defense of trans people. “In our countries, our deaths go unpunished and we are not given justice. That is why we often flee our countries to try to save our lives.”

According to a report published last year by the organization Red sin Violencia (Network without Violence) that examined crimes against LGBTQ people in the Caribbean and Latin America, 39 LGBTQ+ people in Guatemala were murdered in 2023, which represents “a 34.5% increase in the number of cases and a 28.7% increase in the homicide rate compared to the previous year,” marking the most violent year on record against LGBTQ people in that country.

Guatemala has passed conservative measures including banning same-sex marriage and increasing abortion penalties.

Emile DuPuis Maurus, an attorney with Border Butterflies, a group that supports LGBTQ+ asylum-seekers, is in close contact with clients who are grappling with the repercussions of the Trump administration’s executive orders.

DuPuis Maurus, who is trans and lives in Tijuana, Mexico, said that after the suspension of the CBP One application, many people from the LGBTQ+ community who had appointments scheduled to present their asylum cases in the U.S. or requests for other protective measures, such as suspension of deportation and protection under the Convention against Torture, have been forced to remain in Mexico.

“All appointments were canceled, so there are a lot of people here who don’t know what to do,” he said.

In Los Angeles, Santos-Zacaría keeps busy working in a Mexican restaurant and living near family members. She’s hopeful she will be able to stay in the U.S.

“When I win the case, I will have a party to be happy again,” she said. “I think I will be born again.”

An earlier version of this story was published in Noticias Telemundo.