At Infobae, an online Argentinian newsroom established in 2002, a quiet revolution has taken place: the data team established by veteran data journalist Sandra Crucianelli is now made up entirely of women.

When she started hiring her data team seven years ago, she was not looking to hire women in particular, that was just a happy coincidence. “I did not look for members based on their gender. I only focused on looking for the best [candidate] for each task,” she says.

But it’s a far cry from the landscape she encountered when she first started working back in the 1980s. At that time, the industry, at least in Argentina, where she is based, was dominated by men, and data journalism was a niche field.

“Back then, what is known today as data journalism did not exist. We did investigative journalism using spreadsheets but in a very exceptional way,” she says.

Her journey from biochemistry to the trenches of data journalism has been one of persistence and passion, but her experiences have also mirrored a shift in the industry landscape.

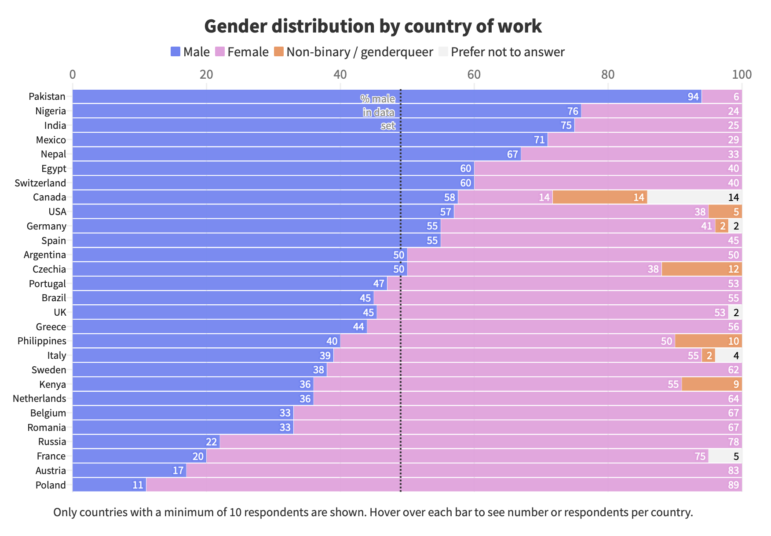

In the demographics section of the 2023 State of Data Journalism survey — carried out by the European Journalism Centre but looking at the global panorama — 49% of respondents identified as men, 48% as women, 1% as non-binary / genderqueer. The near parity between men and women, the authors wrote, showed “a significant shift” from 2022 when 58% of the respondents were male and 40% identified as women.

The global breakdown of gender distribution, however, reveals some stark differences: in Pakistan, for example, 94% of people responding to the survey identified as male, in Nigeria the figure was 76%, and in Mexico 71%. While this is just one survey, and reflects those who chose to contribute, it suggests there are places where women still face obstacles and data journalism is a male-dominated field.

The latest State of Data Journalism survey from 2023 explored the industry’s demographics, looking at the gender breakdown in different countries. Image: Screenshot, European Journalism Centre

For International Women’s Day this year, GIJN decided to speak to women from different parts of the world about their journeys in data journalism, how they got into the field, what their experiences have been, and to find out if there are still structural barriers or challenges holding them back.

Getting Started in Data Journalism

For Crucianelli, becoming a data journalist was a gradual process. A scientist by training, she found herself drawn to the unfiltered truth hidden within data. “My academic background does not come from journalism, but from science. I studied biochemistry for several years at university and although I did not graduate, I did study mathematics, so numbers always caught my attention.”

The first step was to immerse herself in investigative journalism. It was the rise of computer assisted reporting in the 1990s that led her to data journalism, and eventually to Infobae where she established her own team. She and her colleagues have won prizes and plaudits for their work on the FinCEN Files, the secret decrees of Argentina’s military dictatorship, and the Panama Papers.

A number of women told us their first forays into data journalism were driven by a desire to tell stories and make sense of the world around them — for which numbers and data offered a pathway.

E’thar AlAzem, executive editor at Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, loved numbers and puzzles even as a child and this, years later, led her to data journalism. “I’m constantly driven by the quest for evidence, and data journalism fulfills this passion,” she says.

Savia Hasanova, a data analyst based in Kyrgyzstan, who transitioned to the field from policy research, found herself drawn to the power of numbers to illuminate social issues. “I realized that I could bring new insights and knowledge to a broader audience and use my analytical background to become a data journalist,” she explains.

For Hasanova, data journalism isn’t just about numbers, it’s about giving voice to the marginalized. “We use data to report on domestic violence, violations of women’s and girls’ rights, and the discrimination we face,” she says, emphasizing the ability to “reshape narratives and amplify voices that have long been ignored.”

Pinar Dağ is a data journalist educator, judge for the Sigma Awards, and GIJN’s Turkish editor. Image: Courtesy of Dağ

Pinar Dağ is a data journalism educator and practitioner in Türkiye, a judge of the Sigma Awards for Data Journalism, and GIJN’s regional editor in Turkish. She was working as a journalist in London when the WikiLeaks story broke — and that got her interested in the systematic analysis of documents and data. She has now been teaching data journalism for 14 years, providing access to many other journalists who, like her, are interested in the power of data to tell investigative stories.

When asked what, if anything, women bring to the field that is different to their male colleagues, she highlights how some bring a “feminist” approach. “When you look at the diversity of data journalism topics, you can see that there is empathy, sensitivity, different and diverse perspectives, the details of human-centered stories are worked out very well, and gender-sensitive analyses are made,” she notes.

It is a point echoed by Hassel Fallas, the founder of Costa Rica-based La Data Cuenta. She emphasizes the importance of a gender perspective in data analysis which women often bring to newsrooms from lived experience, particularly in the age of AI. “Gender biases in data often obscure the specific challenges women face, making gender-conscious analysis essential for a more accurate and nuanced depiction of reality,” she says.

Helena Bengtsson, the data journalism editor at Gota Media, started out in the ‘90s and says she is generally “not very fond of gender generalizations.” But when asked what women bring to data journalism she says, “If there is anything, maybe attention to detail.”

“I think that is the most important trait in a data journalist,” she adds. “You can always learn the different programs and methods — but if you can’t pay attention to details and at the same time see the whole picture, you’re not a good data journalist.”

Kenyan data journalist Purity Mukami had a background in statistics when she started in journalism. She says her boss at the time — John Allan Namu, the CEO of Africa Uncensored — recognized her background could be useful for election reporting and from there, her path into data journalism was set.

Mukami points out the significant role mentors can play, and says that in newsrooms across the country she has constantly encountered women who would not be there had it not been for the intervention of veteran data journalist Catherine Gicheru. “She has done so much to strengthen and connect a lot of women data journalists, through the WanaData program,” Mukami says, about the Pan-African network of journalists, data scientists, and techies that gives women journalists the opportunity to collaborate and work on data journalism projects.

Gicheru, who led WanaData and is the director of Africa Women Journalism Project, says that a scarcity of training opportunities available for women when she was a reporter meant she had to learn on the job. But she saw in the field and in her newsroom how important it was to have women be a part of the conversation.

“One of the most eye-opening moments for me was when we worked on a story about maternal health. We had heard about women dying in childbirth, but when we analyzed hospital records and government data, the numbers were staggering — far worse than what individual stories suggested,” she recalls.

Gender Gap?

As for what’s next, Mukami, who now works for OCCRP, says that while her experience has been one of equality in the newsrooms she has worked in, more broadly there is still a sense that women don’t get promoted to senior or leadership positions as often as men. “I also believe women are stereotyped as being emotional and therefore rarely get managerial roles in this space. Finally, with the new tools and skills one needs to learn while being a wife and a mom in an African setting, [it] can be overwhelming,” notes Mukami.

Hassel Fallas, founder of the Costa Rican-based data journalism site La Data Cuenta. Image: Courtesy of Fallas

Fallas also pointed to this issue — saying that while the growing numbers of women in data journalism is great, what matters more is, “whether women have the same opportunities for leadership and professional growth.” She has noticed a persistent gender gap in journalism. “While women make up approximately 40% of the journalism workforce, they hold only 22% of leadership positions in media organizations,” she says, citing figures reflected in recent editions of the Reuters’ Institute’s report on women in the news.

“This disparity reflects structural barriers, including limited access to decision-making roles and the ongoing need to prove our expertise in male-dominated environment,” Fallas adds.

Gicheru also feels that gaps remain when it comes to fair representation of women leaders in the field. “In leadership, there are still fewer women, which means fewer role models and mentors for the next generation,” she explains. One of the reasons she feels there are less women in data journalism in some places is because, “it has long been seen as a ‘tech-heavy’ space, which meant that many women were discouraged from pursuing it.”

She also points to another reason there are fewer women in leadership positions — cultural barriers. “Many women journalists, especially those in smaller newsrooms, juggle multiple responsibilities — reporting, editing, and sometimes even administrative work — while their male counterparts focus solely on investigative work,” she points out.

Crucianelli says one way to overcome these systemic problems is to encourage more data journalism across the profession. “What is needed are more data units in newsrooms. There are important media [outlets] in several countries that do not even have one,” she notes.

Having women in data journalism will “challenge systems, expose inequalities, and push for change”, says Gicheru. For her, “data journalism is not just about numbers — it’s about power. It’s about shifting the narrative so that women and marginalized communities are not just footnotes in news stories but at the center of them.”