As extremism continues to spread across sub-Saharan Africa, journalists are increasingly challenged to track the networks and physical movement of these often violent groups.

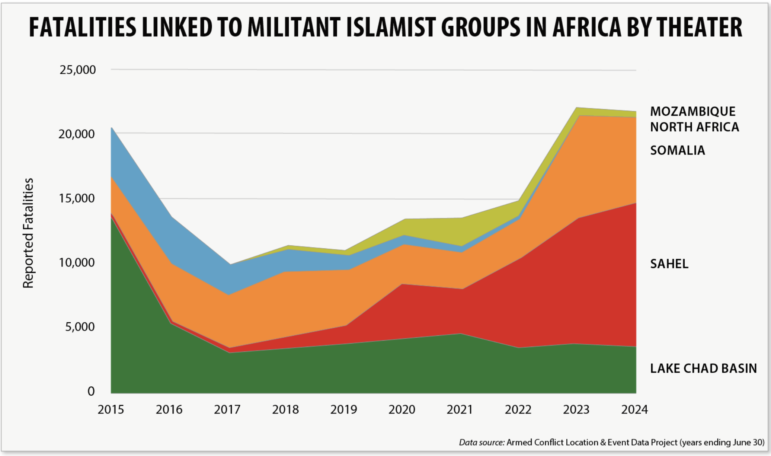

According to the reports from groups like the Africa Center for Strategic Studies and the Council on Foreign Relations’ 2024 Global Conflict Tracker, extremist groups like Islamic State-West Africa Province (ISWAP), Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), and Jama’at Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) have been expanding their influence in the region for the past decade, particularly in the Sahel. By exploiting weak governance, chaotic political leadership, economic decline, and the worsening effects of climate change, these groups have grown in strength, threatening to spread humanitarian crises and instability across Africa.

These organizations routinely operate in secrecy, spreading radical ideologies with limited external oversight. However, investigative journalists can leverage open source tools to uncover hidden networks, expose extremist activities, and challenge the groups’ propaganda efforts. By examining digital footprints, social media interactions, geospatial location, and encrypted communications, reporters can uncover how these organizations operate and spread influence.

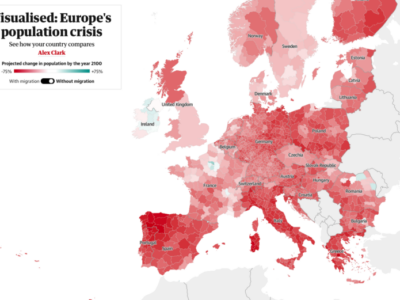

Using data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies has documented a marked increase in violence and fatalities in the past few years due to extremist groups in the Sahel. Image: Courtesy of Africa Center for Strategic Studies

Social Media as Investigative Environment

Aliyu Dahiru, head of HumAngle’s radicalism and extremism desk, routinely turns to open source intelligence (OSINT) resources to track these extremist groups, analyze their radicalization strategies, and expose how local groups expand into global networks.

In recent years, he has reported on the activities of these violent, non-state actors including the “soft-jihad” recruitment propaganda tactics of ISWAP and the Islamic State’s exploitation of social media to expand their areas of influence.

“Sometimes, I infiltrate jihadist groups using a sockpuppet account, an alias created specifically for investigation,” Dahiru says. Using a step-by-step process, he looks to gain access to one account of the extremist, then join another account and another to gather data for investigation. “They advertise their accounts in Telegram groups, making it possible to snowball and compile large pools of data over months.”

Dahiru notes that extremist propaganda in his region has increasingly migrated online to platforms like Telegram and TikTok, which have more lenient moderation than those of Facebook and Twitter/X. As a result, Dahiru adapted by developing strategies to scrape data and scrutinize their propaganda materials.

“Most of their communications are not in standard Arabic but in dialects, making it difficult for automated moderation tools to flag them,” he explains. But his understanding of both Arabic, which he studied formally, and the Hausa language popular in the region allowed him to interpret their messages.

For his 2023 investigation on The Dark World of Jihadist Propaganda Channels on Telegram, Dahiru spent months cross-referencing and tracking activities to be confident that he had found the official channels of Ansaru, an Al-Qaeda-affiliated terror group based in Nigeria. With a combination of behavioral analysis, linguistic expertise, and propaganda examination, Dahiru was able to follow the spread of Ansaru’s extremist ideology through educational materials and online discussions.

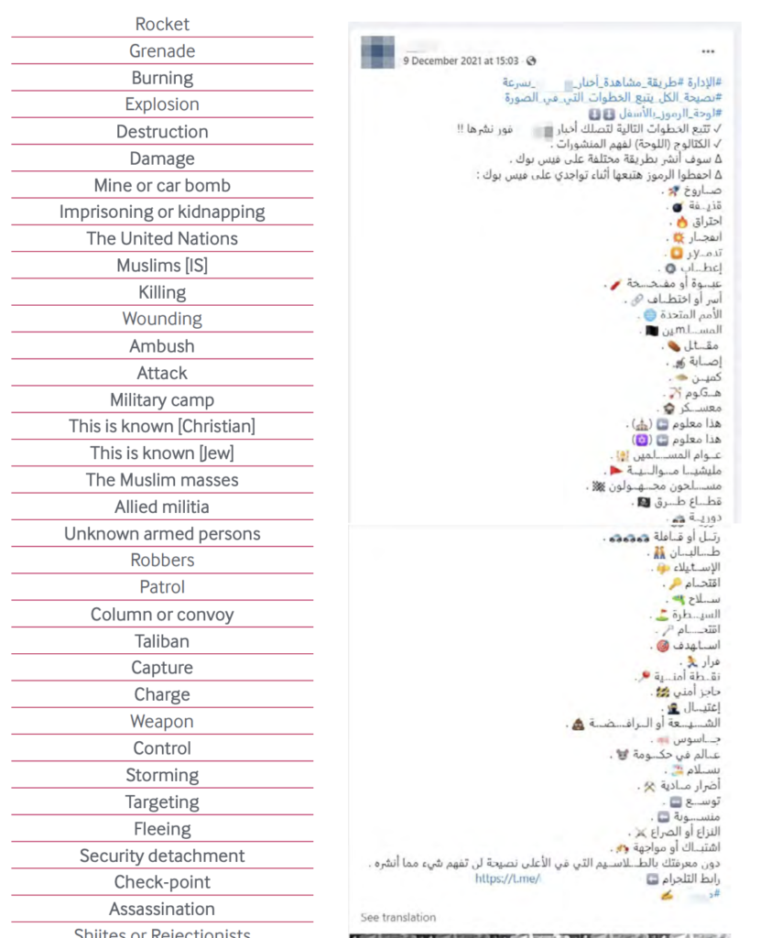

As part of his reporting, he learned an important bit of tradecraft: extremist groups often employ coded language online to evade detection and hide in plain sight when publicly discussing their plans or activities.

“For example, jihadist groups use emojis to signal their intentions,” he explains. “A bomb emoji may indicate an attack, while a certain animal or gesture could reference a specific target.” Understanding these subtleties required extensive monitoring and contextual analysis.

“Researching extremism and understanding their encryption is not something you learn overnight,” he points out. “It requires patience, familiarity, and time spent tracking how they encode their messages.”

Through digital tracking and interpretation, HumAngle reporter Aliyu Dahiru was able to build a spreadsheet of emojis that a terror group was using as code words to disguise online discussions of its plans. Image: Courtesy of HumAngle

Surveying the Battlefield Online

In his investigation into the ongoing war in Sudan between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Mike Yambo, an OSINT investigator with Kenya’s The Nation, relied on chronolocation techniques using Sentinel Hub and NASA FIRMS to uncover the extent of destruction, verify atrocities, track RSF activities, and expose human rights abuses.

Beyond satellite analysis, Yambo monitored the digital battlefield where both groups flooded platforms like Telegram and X (formerly Twitter) with propaganda and battlefield updates. Amidst grainy footage, shaky phone recordings, and blurred images circulating online, as well as analyzing social media posts from both official and unofficial accounts, he pieced together real-time developments, verified attack claims, and tracked the forces’ movements.

“Most videos and photos contained key identifiers, like landmarks and buildings, allowing me to geolocate the exact spots where they were filmed,” he explains. “By analyzing satellite imagery, I was able to confirm attack locations, document the destruction of cities, towns, and villages, and track shifting frontlines.”

However, satellite images alone weren’t enough. To establish the timeline of these atrocities, Yambo compared imagery over time. “Chronolocation helped determine when specific events occurred, adding a layer of verification to witness reports and social media claims,” Yambo adds.

Verifying Misinformation

In a conflict zone where misinformation spreads rapidly, journalists also face great challenges and difficulty in reporting. Violet Ikong, a conflict reporter and fact checker for The Cable, relies on a variety of OSINT tools to verify facts, counter misinformation, and ensure accuracy in reporting extremism.

While investigating the propaganda of Ambazonian a rebel group in Cameroon, she encountered social media misinformation about their alleged cross-border attacks on Nigerian communities.

“People share misleading videos and photos, sometimes events that happened 10 years ago, claiming they occurred this morning in a warring community,” she says. “I always rely on trusted tools, trusted platforms, like the Reverse Image Search, to establish where a particular picture was first shared. I then subject whatever information I get to verification to ensure it is accurate and factual.”

To verify claims of the purported attacks, she used the open source tool Who Posted What? to identify over 340 Facebook posts with keywords related to the group. Likewise, she turned to reverse image search tools like TinEye to trace the original source of the images and find any time stamps and additional context of the viral content. This helps uncover whether a photo or video was manipulated, outdated, or taken from a different country.

The investigation ultimately found that numerous social media accounts linked to supporters of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), a Nigerian separatist group, were behind the misleading information about the supposed incursions by the Ambazonian rebels.

Geolocating Extremist Movements

To identify extremist locations, camps, logistics routes, and other zones of influence, journalists can utilize open source tools like Geographic Information Systems (GIS).

Mansir Muhammed, a GIS/OSINT specialist and colleague of Dahiru’s at Humangle Media, says that tracking the extremists starts with trying to understand the space that they operate, where have they been seen, and the paths they take, pieced together by using social media data and geospatial analysis.

One of Muhammed’s most significant investigations mapped the movement of Lakurawa insurgents in northwest Nigeria, an area with rising extremist activity. Lakurawa, a local terrorist group that has a clear structure, long-term goals, and coordinated strategies, has become a violent, destabilizing force as significant as Boko Haram.

“I started the investigation with intelligence gathering, analyzing reports from security sources, media coverage from the militant groups, and I also used on-the-ground sources,” Muhammed recalls. Social media also played a crucial role in his investigations, as extremists often post violent videos where they are executing their victims as well as propaganda films that aim to incite fear. When analyzed for metadata such as timestamps and geographic coordinates, these videos can reveal their locations.

“For instance, a TikTok video of armed militants in a rural area might give away their location if you analyze the shadows, vegetation, and terrain,” he explains.

To confirm the intelligence gathered, Muhammad turned to Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) records to cross-reference historical reports of non-state actors. The step is crucial in establishing a timeline of insurgent movements and validating key locations. Using ArcGIS, a platform used for mapping spatial analysis, and geographic modeling, Muhammed mapped the landscape and identified potential communities that may be affected by direct attacks, movement corridors, and hidden operational bases of the militants.

Uncovering Terrorist Funding

Kunle Adebajo, editor for the Africa Academy for Open Source Investigations, lauds OSINT as a key methodology for his investigations on the operations of extremists in Nigeria.

“The beautiful thing about open source intelligence is that the tools and resources have limitless potential,” he explains. “Even when a tool is created with one purpose in mind, it can serve many others. A journalist must learn the basics and constantly update their knowledge of existing technological possibilities that can aid their work.”

Kunle’s 2024 investigations revealed the funding mechanisms behind terrorist activities in southeastern Nigeria. The report focused on the Biafra Republic Government in Exile (BRGIE) and its alleged fundraising operations.

He used social media search engines to locate relevant conversations and live videos of the group’s meetings. “I downloaded the videos, extracted the necessary data, and analyzed them using Google Spreadsheet,” he says. He then employed a data scraping tool to collect and examine thousands of tweets from Simon Ekpa, the group’s leader on Twitter/X.

But identifying financial sources was only part of the puzzle. To establish a connection between these fundraising activities and acts of violence, Kunle also turned to the ACLED database. “By filtering the statistics, I was able to show a clear correlation between fundraising activities and violent incidents in the region,” he notes. To make the findings accessible, he visualized the data using interactive infographics using Flourish.

Challenges and Limitations of Open Source Tools

Ethiopian freelance journalist Ermias Mulugeta, who has investigated Al-Shabaab’s financing and arms smuggling to Somali youths, acknowledges the importance of having a wide range of OSINT skills and tools to investigate extremism.

However, investigating extremism in Africa, where it is mostly driven by ethnic and religious motivations, presents a complex and perplexing challenge. The difficulty of uncovering the truth increases in such cases, as OSINT sometimes only provides limited assistance. Mulugeta explains that this forces journalists to rely on their cognitive skills to adapt OSINT tools to their understanding of the issues.

“If the writers lack sufficient knowledge about the topic they are addressing, OSINT alone cannot offer significant help,” Mulugeta explains. The nature of extremism in the region is layered, and without a deep understanding of these dynamics, open source tools can only get reporters so far. A surface-level approach to OSINT cannot unravel the deeper motivations behind extremist actions, which requires additional information using real-world and on-the-ground reporting.

“I’ve personally encountered several instances where data collected through OSINT tools turned out to be unsubstantiated, forcing me to cross-check manually, which was incredibly time-consuming,” he notes.

Expanding Role of OSINT in Conflict Investigations

The process of OSINT investigations is both technical and adaptive. From using fact-checking tools like reverse image search to verifying old footage to employing geospatial data for location tracking, every case demands a unique set of methods. As these groups continue to exploit social media to spread propaganda and recruit new members, anyone tackling such groups must take into account their online activities.

Beyond monitoring social media, OSINT tools allow investigators to map out locations, identify group members, counter misinformation, and expose funding sources. These reporting tactics help to bring accountability to the actions of these extremist groups and will “weaken armed groups by exposing their sources of funding and limiting their access to victims, sympathizers, and potential recruits on the internet,” Kunle says.