One of the leading environmental investigative journalists in Brazil is Hyury Potter, a freelance reporter who recently won the Pulitzer Center’s Breakthrough Journalism Award.

The prize recognized those who pursue investigative journalism and in-depth reporting on “often-overlooked topics in regions frequently neglected by mainstream media.”

Born and raised in the Amazon, Potter has spent his career covering illegal deforestation, mining, corporate misconduct on Indigenous lands, and human rights violations. A graduate of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), he has worked in the Deutsche Welle newsroom in the German city of Bonn, at newspapers in the Brazilian states of Santa Catarina and Pará, and has had work published by Repórter Brasil, BBC Brazil, NBC News, The Intercept, InfoAmazonia, and Mongabay.

Among his most impactful projects is Mined Amazon, a real-time map that continuously tracks illegal mining requests in Indigenous lands and conservation zones, shedding light on environmental threats in the region.

In this Q & A, part of GIJN’s ongoing interview series with leading investigative journalists, Potter shares his experiences of reporting in the Amazon, along with lessons and advice he has gathered throughout his career.

GIJN: Of all the investigations you’ve worked on, which has been your favorite and why?

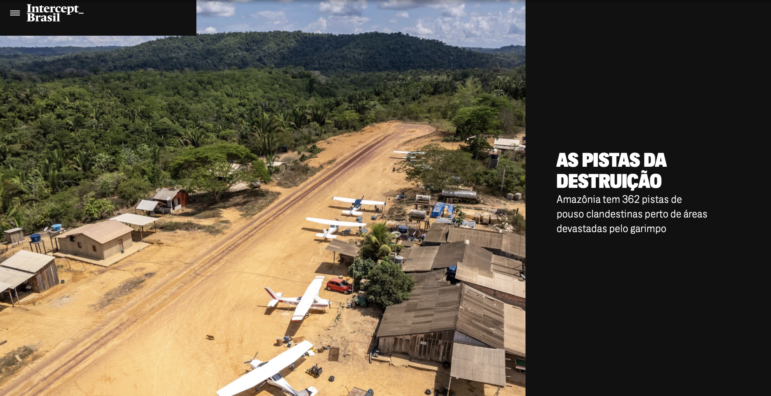

Hyury Potter: It’s a very cruel question, it’s hard to choose one. Thinking about the most recent stories, I like the Amazônia Minada — or Mined Amazon — project, a map I made with InfoAmazonia that detects, in real-time, mining operations affecting Indigenous lands and conservation areas in the Amazon. I also like the research I did during my first year as a fellow at the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network. In collaboration with Earth Genome NGO, we found 1,269 clandestine airstrips in the Brazilian Amazon, almost 400 of which were directly related to gold mines.

GIJN: What are the biggest challenges in terms of investigative reporting in the region you work in?

HP: Maybe the main challenge is still obtaining resources for safe field trips. Traveling in the Amazon is very expensive, and sometimes, it takes days just to get to the location where you’ll conduct the interviews.

GIJN: What’s been the greatest hurdle or challenge that you’ve faced in your time as an investigative journalist?

HP: When I investigated clandestine gold mining airstrips in the Amazon, on at least two occasions I had to talk to armed men during interviews. We were in remote areas, without any protection from the state, so this is something very dangerous. One thing to keep in mind is that when we talk about investigative journalism in the Amazon, the main thing is always to think first about the safety of the team and the people who we are going to interview.

GIJN: What is your best tip or trick for interviewing?

HP: Sometimes, the best thing to do is not interrupt the interviewee. In these situations, people often say more than they should.

GIJN: What is a favorite reporting tool, database, or app that you use in your investigations?

HP: I use QGIS a lot to analyze geo-referenced data with satellite images, and this can be very helpful in journalism investigations. For example, suppose you have information like the location of hotspots of deforestation and also of land and its owners; you can combine the data and identify the owners of the farms driving deforestation in the Amazon. In one of my investigations, I used it to find the possible owners of illegal airstrips connected to illegal gold mines in the Amazon.

GIJN: What’s the best advice you have received in your career, and what advice would you give an aspiring investigative journalist?

HP: Investigative journalism is never the work of just one person, so always try to work alongside other colleagues and collaborate with other media outlets. This will certainly improve your investigation.

Hyury Potter’s 2022 investigation for The Intercept Brasil found 362 clandestine landing strips near areas devastated by mining. Image: Screenshot

GIJN: Who is a journalist you admire, and why?

HP: I admire a lot of colleagues. One is the journalist Lúcio Flávio Pinto. He’s from my hometown, Belém. He won several international awards denouncing the irregularities of giant mining companies in the Amazon and was persecuted for years by people with great economic power, but he still continued his work. At the end of the 1980s, he even created his own newspaper to continue publishing his reports.

GIJN: What is the greatest mistake you’ve made, and what lessons did you learn?

HP: One of the first interviews I did, for a college assignment on the history of the press in my city, I interviewed Pinto. For some reason, I didn’t record that conversation and I regret it to this day. So I’ve always taken care to record big interviews ever since.

GIJN: How do you avoid burnout in your line of work?

HP: I try not to go on [too many] field trips in a row, it’s important to take some rest. When I’m at home, I run or go to the gym at least four times a week, it’s a good thing to do to avoid thinking about work. Sometimes I prefer to pursue stories with a positive message. I’ve dealt a lot with stories that denounce bad things, so it’s nice to see that some actions give a little hope.

For example, in November 2024, I spent a few days with the Parakanã Indigenous People, who are reclaiming their territory after the government expelled invading farmers. It was amazing to be a spectator of the historical moment when an Indigenous community recovered their territory. That was something I was very happy to witness.

GIJN: What about investigative journalism do you find frustrating, or do you hope will change in the future?

HP: Often, even if we publish a story showing something wrong — with several pieces of evidence — we don’t get the expected impact. Journalism alone can’t change anything, it needs the support of society for that to happen.