Russian authorities continue to conceal the scale of their military losses in the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Only independent journalists and researchers attempt to count the dead.

On the third anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the independent exiled media outlet Important Stories (IStories) launched Charon — a database of Russian military casualties built using a custom AI trained by our newsroom.

This algorithm collects all publicly available reports about Russian soldiers killed or missing in action. We’re sharing this data with any journalist or researcher interested in the subject. Right now, the project is available only in Russian, but an English version is on the way.

Katya Bonch-Osmolovskaya, editor of IStories’ data department, explains how the AI was trained, what kind of data Charon can collect, and why journalists should start learning to work with neural networks.

How Journalists Track Russian Military Losses

Lack of official data was an issue in Russia for many years. The first big problem we, as journalists, faced during the COVID-19 pandemic: Russian authorities did not manage to track all the losses and provide real numbers. Independent journalists did it for them.

The next big issue came up when Putin started a full-scale invasion. From the start, the Russian government has been hiding real casualty numbers. So, independent journalists again started to do the job for them.

After three years of the full-scale war, we have found out three ways to give a perception of casualties. The data department of IStories is counting numbers using the excess mortality method of analysis, like we did during the pandemic. Meduza and Mediazona are using inheritance records. Also, Mediazona, BBC Russian Service, and volunteers are collecting obituaries from social media and local news, searching the data by hand.

Through its AI searching, IStoires was able to find the date of death or disappearance is known for 56,500 of the dead and 4,900 of the missing. Here, the deaths and missing are plotted over time, showing that the Russian forces suffered their heaviest losses in January 2023. Image: Screenshot, IStories

IStories began compiling data from social media on casualties at the very start of the invasion. We had a page on our website that was updated daily at first, then weekly. But as time went on, the number of obituaries grew overwhelming. We simply couldn’t keep up — even if our whole team focused solely on this, it wouldn’t have been enough.

At the same time, we understood how important it was to have a list of the dead, including details like their names, region, age, date of death, etc. Such a database is crucial for almost any research about the war.

While searching for a way to streamline the process, we decided to train our neural network. The project got the inside name Charon, after the figure from Greek mythology who ferried the souls of the dead across the river Styx. In the myths, every soul passed through Charon, just like our AI processes every public message about a Russian soldier killed or missing in the war in Ukraine.

Training the AI

We started by compiling a list of keywords the parser would use to search for posts about fallen soldiers, built through trial and error after reviewing hundreds of obituaries.

One of the first problems we faced was that we couldn’t filter just for posts that explicitly mentioned the war. People referred to it in all kinds of ways — “war,” “SVO,” “special military operation” — or using euphemisms like “died defending our homeland.”

So instead, we decided to gather all death announcements and train the neural network to distinguish between deaths related to the war and unrelated ones. Our data team manually reviewed hundreds of obituaries, tagging each as “war-related” or “not.” This labeled dataset became the basis for Charon’s training.

At the start, the AI had some spectacular mistakes: for example, Charon thought that actor Alan Rickman had died in the war in Ukraine.

In total, training took about a year. By fall 2024, we had finalized the current version of the algorithm.

Today, Charon can not only identify whether someone died in the war. It can distinguish between soldiers killed in combat and those who previously served in Ukraine but then later died in Russia under circumstances unrelated to the war.

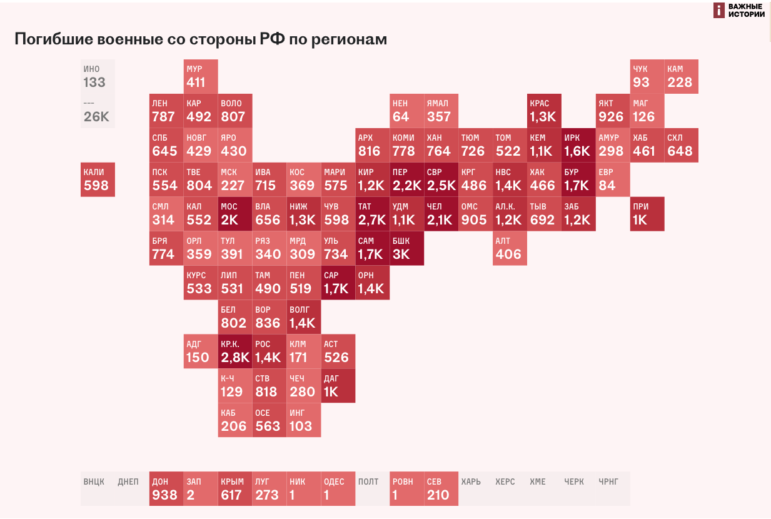

Using the AI Charon tool, IStories has mapped Russian war deaths across regions of the country. Image: Screenshot, IStories

How the AI Works

Charon searches through public death announcements, tagging each as “yes, war-related” or “no, not war-related.” For the “yes” entries, it extracts attributes from the text — age, deployment date, region, and so on. If a piece of information is missing, the corresponding field is left blank.

Next comes manual verification. We check the AI’s entries and fill in any missing details, including data from leaks or additional sources.

Sure, mistakes still happen — sometimes a name or date is incorrect, or automation fails at some step. We’re aware of these limitations, and we encourage people to report errors so we can fix them.

Was it worth spending a year training the AI? Yes, because verifying and supplementing existing data is far faster than collecting it all manually.

For 11,000 Russian soldiers, IStories’ Charon was able to map the places of their death and disappearance on the territory of Ukraine, down to a specific region. Image: Screenshot, IStories

How Complete is the Data?

According to our colleagues, only 40–60% of death reports of Russian soldiers ever reach the public. We can’t change that. We can only work with what’s out there.

We believe that within this range, Charon is capturing a large share. It regularly finds people who were missed by other projects. Early in the training process, we’d find one new name for every 100 war deaths identified. Now it’s around 30 previously uncounted names per 100 unique finds.

What Kind of Data Do We Collect?

“Military losses” typically include those killed, missing, captured, severely wounded, or who deserted. But the last three are hard to estimate. Most open source tracking focuses on the dead.

Charon, however, allows us to track not only Russian soldiers, but also:

- Residents of occupied Ukrainian territories killed in the war, many of whom were forcibly mobilized after February 2022.

- The missing. This is harder due to the uncertainty. Is someone alive but imprisoned? Dead and unrecovered? Still, this category is key to understanding the full scale of Russian losses.Based on our estimates, about 20% of those listed as missing eventually end up confirmed dead. When that happens, we move them from the “missing” category to the “killed” category — meaning we’ve already accounted for the loss, and only their status changes.

- Foreign nationals who fought on Russia’s side.

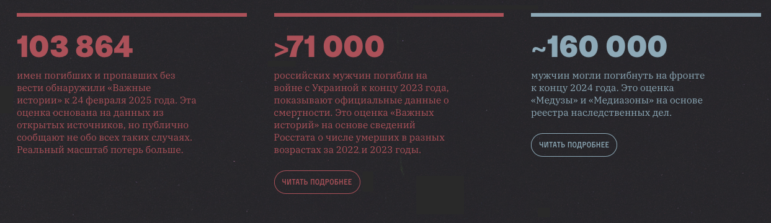

As of February 24, 2025, we’ve identified 103,864 killed or missing individuals by name. And we still have a massive backlog.

Thought the third anniversary of the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, IStories had identified 103,864 names of Russian military war dead and missing. But other estimates (right) from sites like Meduza and Mediazona, which included inheritance information, suggest the total figure could be almost 60,000 higher. Image: Screenshot, IStories

To give you a sense of scale: around 50,000 reports of missing persons and 10,000 reports of confirmed deaths still haven’t been reviewed. Plus, we haven’t even started analyzing the newest reports from recent weeks. These are messages, and some names may appear multiple times. But still, the unprocessed data is huge. We’ll continue updating the project page as we work through it.

Most importantly, we’re committed to sharing this database with other journalists and researchers.

Why We’re Sharing the Data

Given the scale of what Charon collects, this dataset is a goldmine for research. If we kept it to ourselves, we’d never be able to explore its full potential.

We believe that the more smart people dig into the data, the more we’ll learn about the war.

Right now, both the project site and the full dataset are in Russian only. But we’re working on an English version.

If you’d like access to the data, write to: [email protected]

IStories’ Takeaway on Working with AI

AI allowed us to build and maintain a database of Russian military losses without dedicating our entire newsroom to it full-time. For us, that makes the project a success.

I believe that right now is the time for newsrooms to — if not run headlong into AI — at least lie down in its general direction. Otherwise, there’s a real risk of being left behind.

Every newsroom has some repetitive tasks with a clear set of steps. It’s far more efficient to hand the technical parts over to AI and focus our time and brainpower on what matters.