Moroccan journalist Soulaimane Raissouni was arrested outside his home in Rabat, Morocco’s capital city, in May 2020. The editor-in-chief of the newspaper Akhbar Al Yaoum had long been a thorn in the side of the Moroccan authorities, publishing investigations into corruption and state repression — such as a salary bonuses scandal involving the country’s finance minister and the treasurer general.

After being held for a year without trial, Raissouni was sentenced to five years in prison on unproven sexual assault charges decried by human rights and press freedom organizations as politically motivated — and which authorities also used to detain and convict investigative journalist Omar Radi. “They don’t just punish journalists,” Raissouni said before his sentencing. “They go after their private lives to break them.”

His case reflects the broader struggle of investigative journalists in North Africa, where press freedom is in rapid decline and speaking truth to power comes at an ever higher cost.

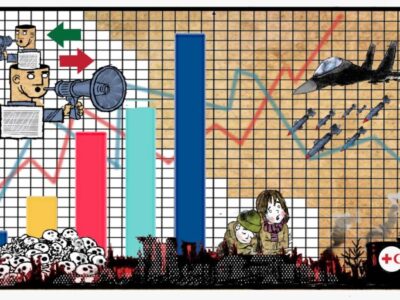

Press Freedom Under Siege

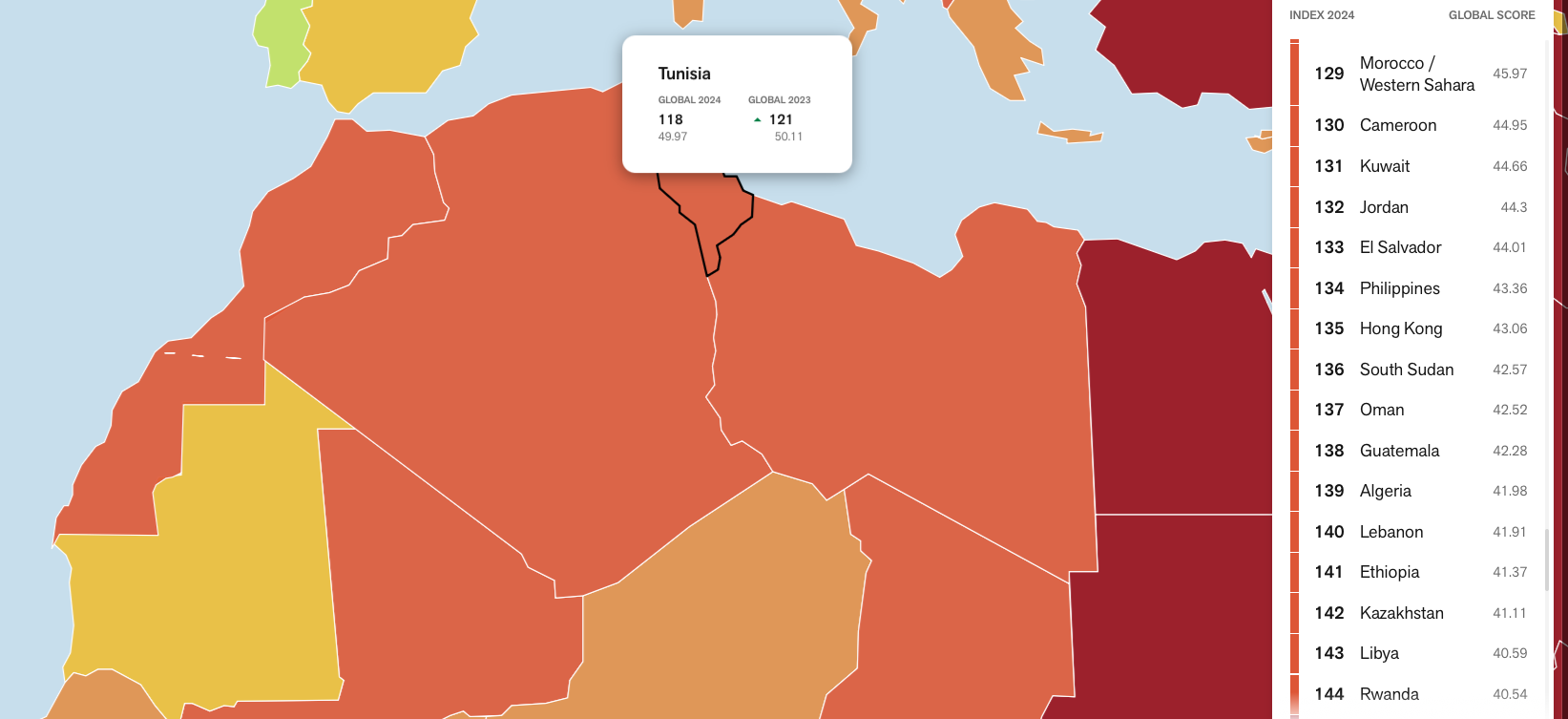

The Maghreb, once a beacon of post-Arab Spring optimism, now ranks among the world’s most hostile environments for journalists. According to Reporters Without Borders’ 2024 World Press Freedom Index, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region remains the worst globally for press freedom, with nearly half of its countries in a “very serious” situation. Tunisia, once lauded as a democratic success story, has plummeted from “free” to “partly free” after President Kais Saied’s 2019 power grab, while Libya (143rd), Algeria (139th), and Morocco (129th) languish near the bottom of the rankings.

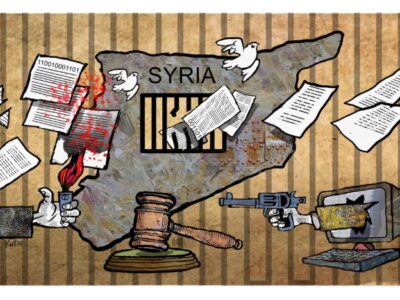

In Tunisia, Decree-Law 54, ostensibly targeting cybercrime and “false information and rumors,” has become — thanks to vague wording and harsh sentences — a weapon to silence critics. Walid Mejri, editor-in-chief of GIJN member Alqatiba, warns of the chilling effect the decree has had on investigative reporting: “Sources are now afraid to speak. This fear is killing investigative journalism from within.” Mejri explains that under Saied’s rule, journalists covering corruption or human rights violations face intimidation and legal threats. “Before, people would speak off the record,” he says. “Now, even that is dangerous.”

The backsliding in press freedom in Tunisia compounds challenges for the country’s women reporters, notes Hanna Zbiss, an independent investigative journalist. “Being a female journalist in Tunisia in the context of the return of the dictatorship is not easy, especially if you are an investigative journalist… We are harassed on social media and [are targets for aggression] for revealing corruption and criticizing the political regime,” she says. “The virtual attacks affect your reputation and personal life, to silence you and even minimize your presence in public spaces.” She adds that while more than half of journalists in Tunisia are women, only a few have access to leadership positions and are underpaid compared to their male counterparts.

Much of North Africa languishes at the bottom of RSF’s 2024 World Press Freedom Index. Image: Screenshot, RSF

Tools of Repression: From Pegasus to Prison

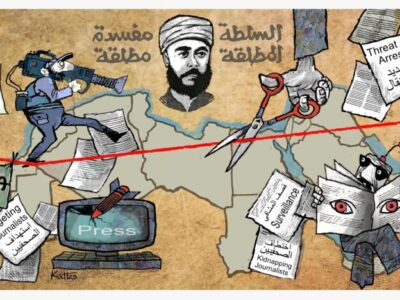

In Morocco, the state has turned to digital surveillance to muzzle the press. For The Pegasus Project, Amnesty International, Forbidden Stories, and 17 partner outlets worldwide documented the use of Pegasus spyware to monitor journalists — which has enabled authorities to gather personal information to use in politically motivated prosecutions. The reporting was underpinned by a leak of more than 50,000 records of phone numbers chosen for surveillance. Before their arrests, Raissouni and fellow journalist Radi were among around 180 journalists targeted.

In Algeria, the repression of investigative journalism has reached alarming levels. “Since [President] Tebboune’s arrival, no major investigations have been published,” says Ali Boukhlef, an independent journalist. “Journalists like Rabah Karèche and Belkacem Houam have been jailed simply for doing their jobs,” he adds. Karèche, a correspondent for the newspaper Liberté, had been arrested after reporting on land-use protests by members of the Tuareg tribe; Houam was jailed for reporting that 3,000 tons of exported Algerian dates were returned from France because they contained harmful chemicals.

The dissolution of the Algerian League for the Defense of Human Rights (LADDH) in 2022 further illustrates the government’s tightening grip on civil liberties. “There is no space left for investigative journalism inside Algeria,” Boukhlef adds. “The only option is exile.”

In Libya, journalists navigate an even more treacherous landscape. With no central authority to protect press freedom, armed militias exert control over media outlets. “Journalists here align with armed factions to survive,” says a Libyan journalist, who requested to remain anonymous given the dangerous conditions for reporters working in the country. “It’s not about freedom of the press — it’s about survival.”

The journalist highlights a recent case that underscores the dangers investigative journalists face — the 2024 detention and subsequent release of journalist Ahmed Al-Sanussi from Libya. Al-Sanussi, the owner of Sada newspaper, was arrested by the security agency shortly after returning to Tripoli from Tunisia. His detention followed the arrest of several journalists from his outlet after they published leaked documents obtained from Libya’s anti-corruption authority that exposed government corruption — including embezzlement of tens of thousands of dollars related to transactions for the supply of COVID-19 vaccines.

With access to sensitive financial leaks and a track record of uncovering high-level corruption, Al-Sanussi was perceived as a threat to those in power — ultimately forcing him to flee the country.

Resilience Amid Repression

Journalists in North Africa continue to resist, finding ways to report the truth despite the dangers they face. In Tunisia, Alqatiba editor-in-chief Walid Mejri explains how investigative journalists have been forced to adapt. “The traditional media landscape is collapsing, and independent journalism is struggling to survive,” he says. “But we refuse to stop. We’re exploring alternative models of funding, leveraging digital platforms, and working collaboratively to ensure critical stories reach the public, such as working under organizations like ARIJ or Article 19 to expand our reach and impact.”

Mejri adds that while censorship and legal threats have increased, journalists are shifting towards innovative methods to expose corruption and misconduct. “We have learned to be strategic — some stories are too dangerous to publish locally, so we find international platforms to amplify them.”

Alqatiba — forming part of a large collaboration with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and more than 70 other outlets globally — uncovered a network of Tunisian business leaders, former sports officials, and members of a former president’s family who owned luxury properties in Dubai without declaring them to Tunisian authorities. Journalists spent months verifying the identities of the people found in a trove of leaked data obtained by the nonprofit Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS) and confirming ownership status with official records, open source methods, and other leaked datasets. The revelations, part of the broader Dubai Unlocked investigation, led to arrests and prosecutions for tax evasion and money laundering.

Mejri underscored the significance of such reporting in an increasingly repressive climate: “We exposed financial mismanagement and forced the government to act. They cannot silence every voice, even if they try.”

Other standout Alqatiba work includes an investigation into a suspected conman, which resulted in the Central Bank of Tunisia freezing his funds and opening a new criminal investigation; their coverage of the failures of the Tunisian economy prompted a public reaction from the Tunisian president. Recent investigations include the bankruptcy and mismanagement of a Tunisian airline and the crisis in Tunisia’s crucial but beleaguered olive oil industry.

In 2024, the independent Tunisia-based outlet Inkyfada worked on a year-long investigation with Lighthouse Reports, Le Monde, The Washington Post, and other partners to uncover racial profiling and deportation practices targeting migrants and refugees in Morocco, Mauritania, and Tunisia — and the role of EU funding in the name of “migration management.” The team of journalists interviewed more than 50 survivors and analyzed dozens of photographs, videos, and testimonials to document and geolocate incidents of people being rounded up in cities or ports in Tunisia. In a joint investigation with the Italian outlet Internazionale, Inkyfada exposed how Tunisian migrants are deported from Italy in secret and without scrutiny, and how airlines colluded in the process.

The Libyan journalist describes how investigative journalists operate under extreme pressure, relying on secure communication channels and anonymous sources to conduct their work.

“We share information through encrypted apps, collaborate with reporters outside the country, and release reports under pseudonyms when necessary,” the journalist explains. “Every investigation we publish is a calculated risk.” The reporter cited an exposé on arms trafficking that was widely shared online despite government and militia efforts to suppress it. “The truth finds a way,” the journalist insists. “Even in the darkest places, people still seek it.” One such investigation, The Kornet Journey, uncovered how advanced anti-tank missiles looted from Libyan stockpiles ended up in ISIS’s hands in Sinai. The report traced their smuggling routes and highlighted their use in major attacks, including the destruction of an Egyptian naval vessel.

In Morocco, Soulaimane Raissouni’s imprisonment has become a symbol of the state’s tightening grip on the press. His case has had a chilling effect on Moroccan investigative journalists, many of whom now avoid sensitive topics like corruption or surveillance. “It’s not just about prison,” he once wrote. “It’s about making sure no one dares to take our place.”

A Path Forward

The future of investigative journalism in North Africa hinges on several critical factors. The most urgent among them is legal reform. Repealing draconian laws such as Tunisia’s Decree-Law 54 and Morocco’s broad defamation statutes is imperative to safeguard journalistic integrity and freedom. Without systemic legal changes, journalists will continue to work in fear, navigating a legal minefield that punishes truth-telling.

International pressure is another vital mechanism for change. The global community must hold governments accountable, imposing sanctions on states that weaponize surveillance technology against journalists. Trade agreements should be conditioned on adherence to press freedom standards, ensuring that economic partnerships do not come at the cost of silencing dissent.

Investigative journalism in North Africa is at a crossroads. The forces working against it are powerful, but the resilience of its practitioners is undeniable. The question is not whether journalism will survive, but whether the world will stand with those who risk everything to tell the truth. As Mejri says: “We are under attack, but we are not defeated. Journalism is evolving, and we will find ways to keep telling the stories that matter.”

On a recent bright afternoon in Rabat, Soulaimane Raissouni — who was pardoned and released in 2024 after his arrest in 2020 — sat at his laptop, sipping an espresso as he typed a column critiquing the misconduct of Morocco’s security apparatus. “I write because I have to,” he said. “If we stop, they will only intensify their authoritarianism and arbitrariness.”