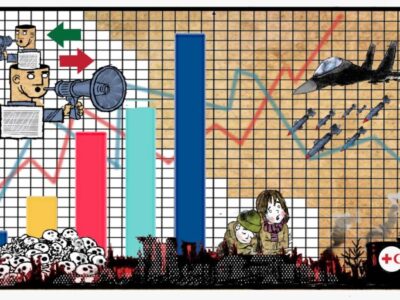

Reporting on Yemen has long been one of the most difficult and important tasks for investigative journalism. The years of conflict and political turmoil make it challenging but crucial to find accurate information and to properly represent its people.

This is where journalists like Nawal Al-Maghafi come in. Raised in Yemen, Maghafi has been presenting documentaries about Yemen and the broader region for years, joining BBC Newsnight as their international correspondent in 2023.

After completing her education at the University of Nottingham, Maghafi returned to Yemen in 2011, where she filmed videos of the Yemeni Revolution and even interviewed then-president Abdullah Saleh.

Throughout the years, Maghafi produced countless reports and documentaries for the BBC, where she focused on salient issues like Yemen’s humanitarian crisis, the infamous Sanaa funeral bombing, political developments with the Houthis, as well as the Yemeni government’s efforts to cover up COVID-19 cases.

Maghafi was nominated for the Royal Television Society’s Young Talent of the Year award in 2018, and her 2019 documentary titled “Iraq’s Secret Sex Trade” won two News and Documentary Emmy Awards. She then received the same award for her reporting on the coronavirus pandemic in Yemen.

In this Q & A, part of GIJN’s ongoing interview series with leading investigative journalists, Maghafi shares with us her greatest struggles and advice she would give to any journalists entering this field.

GIJN: Of all the investigations you’ve worked on, which has been your favorite and why?

Nawal Al-Maghafi: I don’t think I can pinpoint one investigation as my favorite. Each one has taken me to fascinating places, introduced me to incredible people, and shaped the way I see the world in different ways. Every investigation has taught me something new.

That said, the ones I’m most proud of are the ones that have led to real change and impact. For example, our investigation into the sexual exploitation of young girls in Iraq by senior clerics stands out. Shortly after it was released, one of Shia Islam’s most influential clerics issued a new ruling banning temporary marriages to young girls.

Another is Starving Yemen. Returning home and seeing my country torn apart by war was incredibly difficult, but that film led to £40 million (US$51 million) being raised by the Disasters Emergency Committee for Yemen. On my next trip, I was able to meet the same people from the film and see firsthand how that aid had helped them. It’s that kind of impact that keeps me going.

Following the release of the BBC investigation into the sexual exploitation of young girls in Iraq by senior clerics — through a controversial practice called ‘pleasure marriage’ — an influential cleric issued a ruling banning temporary marriages to young girls. Image: Screenshot, BBC

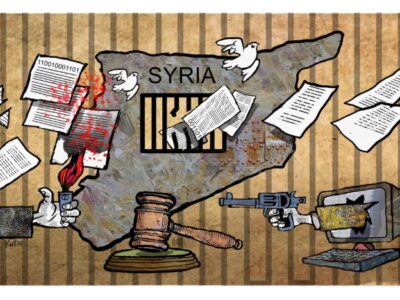

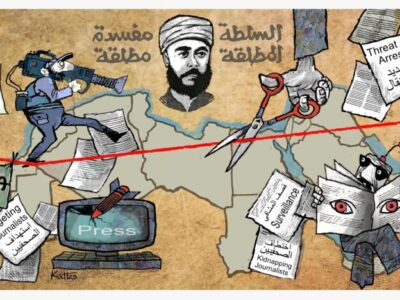

GIJN: What are the biggest challenges in terms of investigative reporting in your country/region?

NAM: Reporting on your own country is incredibly difficult because there’s no separation between the work and your personal life — there’s no real escape once the investigation is over.

For me, one of the hardest aspects is the impact on my family. I chose to be a journalist, and I accept the risks that come with every investigation I take on. But when a story is published and my parents or family members face online harassment or other consequences because of my work, that’s much harder to accept.

I’m incredibly lucky to have supportive parents and family members, but I still feel guilty when they’re negatively affected by something I’ve reported. That’s the part of investigative journalism that never gets easier.

GIJN: What’s been the greatest hurdle/challenge that you’ve faced in your time as an investigative journalist?

NAM: Investigative journalism comes with many challenges, but one of the greatest hurdles I’ve faced is ensuring the safety of sources and colleagues, especially in high-risk environments. Whether it’s dealing with censorship, threats, or the logistical difficulties of verifying information in conflict zones, the responsibility of protecting those who trust you with their stories is immense. There have been times when I’ve had to weigh the risks of publishing certain investigations, knowing that exposure could put people in danger. It’s a constant ethical balancing act — pushing for accountability while ensuring that no one is harmed in the process.

GIJN: What is your best tip or trick for interviewing?

NAM: If I had to give one tip for interviewing, it would be to embrace silence. Ask your question, allow your contributor to answer, and then wait. In difficult, emotional interviews, those moments of silence can be more powerful than words, giving space for raw emotions to surface. In accountability interviews, silence can be revealing — it forces the interviewee to sit with the question, and their facial expressions, body language, or hesitation often tell you more than their actual response. It might feel awkward, but it’s worth it. And in the worst case, you can always edit the silence out later.

GIJN: What is a favorite reporting tool, database, or app that you use in your investigations?

NAM: Honestly, LinkedIn has been one of the most valuable resources for my investigations. While there are more advanced open source tools available, I always go back to the basics. LinkedIn has helped me track down crucial sources, verify employment histories, and connect dots in ways that other databases sometimes can’t. That being said, I do think every journalist should explore open source intelligence tools — platforms like Google Earth and social media platforms like Snapchat, Instagram, and even Telegram channels can be invaluable depending on the investigation.

GIJN: What’s the best advice you’ve gotten in your career, and what advice would you give to aspiring investigative journalists?

NAM: The best advice I’ve received is that you can never stop learning. No matter how many investigations I’ve worked on, each new story feels like starting from scratch. Every investigation requires different tools, skill sets, and approaches, and there’s always something new to uncover. For aspiring investigative journalists, I’d say: stay curious, be persistent, and never be afraid to ask for help. Build strong relationships with colleagues, editors, and mentors — investigative journalism is rarely a solo effort, and having the right people around you makes all the difference.

GIJN: Who is a journalist you admire, and why?

NAM: There are so many journalists I admire, but right now, I have immense respect for the local journalists working in Gaza. They have continued reporting under the most horrific circumstances, often risking their lives to inform the world about what’s happening. This has been one of the deadliest conflicts for journalists in our lifetime, yet they wake up every day and keep going. Their bravery, resilience, and dedication to the truth are incredibly inspiring.

GIJN: What is the greatest mistake you’ve made, and what lessons did you learn?

NAM: Thankfully, I haven’t made any major mistakes, and I believe that’s largely because I’ve had the privilege of working with incredible teams who have guided and supported me. Investigative journalism is a collaborative effort, and having colleagues to challenge your thinking, fact-check your work, and offer a second opinion is crucial. That being said, I’ve learned the importance of double-checking everything, no matter how small. One overlooked detail can change the entire framing of a story, so I’ve developed a habit of questioning every fact, assumption, and source until I’m certain.

GIJN: How do you avoid burnout in your line of work?

NAM: I try to be intentional about disconnecting when I’m with my children. When I’m not working, I make a conscious effort to put my phone and laptop aside and be fully present with them. In this line of work, it’s easy for a story to consume you — you’re constantly thinking about it, making connections, and speaking with sources who may be sharing the most harrowing moments of their lives. Often, these conversations don’t fit into a neat nine-to-five schedule, and I find myself maintaining relationships with sources long after an investigation has aired. But even with that, I make sure to carve out time — at least a few hours a week — where I completely disconnect. It’s not always easy, but it’s necessary.

GIJN: What about investigative journalism do you find frustrating, or what do you hope will change in the future?

NAM: One of the biggest frustrations is the ethical dilemma around keeping local journalists safe. Most investigations would be impossible without the deep knowledge and access that local reporters provide, yet there are times when broadcasting an undercover investigation or publishing certain details would put them at risk. When that happens, their safety has to come first — even if it means shelving a story. I hope that in the future, more resources will be dedicated to protecting local journalists, whether through legal protections, emergency funds, or relocation programs. Their work is invaluable, and they deserve the same level of security and support as international journalists.