CONTENT WARNING: The following article includes mentions of physical violence, including torture, war, and forced disappearances, which some readers may find disturbing.

Over three mild, but chilly nights in early December 2024, as I and hundreds of journalists from all over the world attended the annual Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) Annual Forum in Jordan, two significant events in my life were also unfolding: one public, one personal.

I was about to start covering Syria as an investigative journalist at Reuters — just as the brutal Assad regime that had ruled Syria for more than five decades collapsed dramatically in a battle that lasted a mere 11 days, after more than five decades of iron-fisted rule first by Hafel al-Assad and then his son and successor, Bashar al-Assad, and almost 14 years of civil war.

As these public and private milestones converged, I and dozens of fellow Syrian journalists attending ARIJ scattered to hotel rooms and lobby corners — laptops open, phones in hand — following the events that for so many years had seemed unthinkable.

On the morning of December 8, opposition forces — united under the leadership of the hardline Islamist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) — entered Damascus following a major offensive against regime forces. As videos showing thousands of Syrian fighters and civilians storming the presidential palace, looting its contents, and confirming Bashar al-Assad’s escape to Russia began to circulate, I celebrated the moment with colleagues as I also stood at a pivotal point in my career.

Information Through Conventional Means

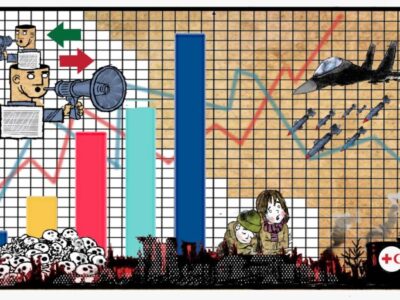

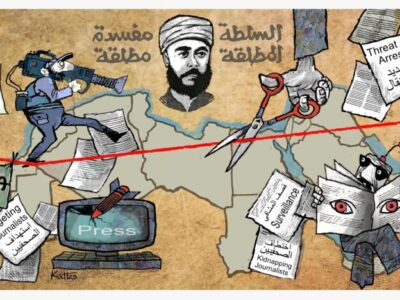

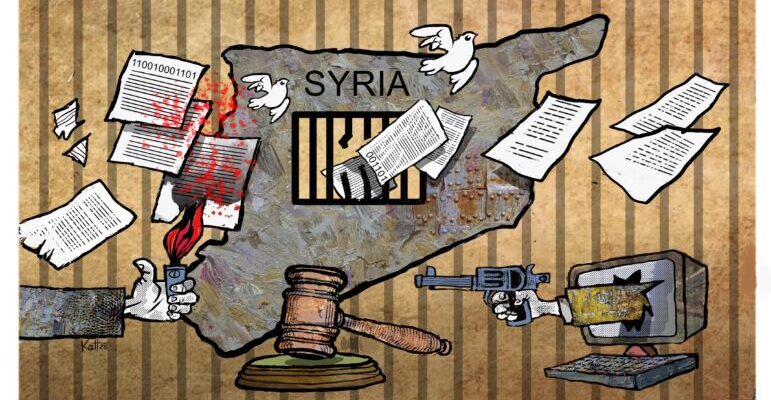

In the last few years, I have focused on investigative journalism because of the Assad regime. Given the difficulty of obtaining information through conventional means in Syria — with the security apparatus controlling all print and broadcast content, the closure of all foreign media offices since 2011, and Syria’s consistent ranking among the bottom five countries in press freedom indices such as Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and Freedom House — it seemed to me the only path forward.

However, after December 8, investigative work has been nothing like it was before. In the past, we built our investigations from a single document leaked to journalists by an insider in state institutions or security agencies. Sometimes, we had to spend extra money through a chain of intermediaries — for precautionary measures like secure transportation or software subscriptions — to protect sources and information. Those who leaked were at risk of being charged with “collaboration with foreign entities,” a crime punishable by death under Syria’s 2012 law.

Talking to sources was no less risky. A single conversation required extensive digital literacy training and was conducted secretly, attempting to evade surveillance systems embedded within the telecommunications network. Later, by examining documents from the notorious Air Force Intelligence branch, we discovered that these systems could record and monitor even the most trivial personal calls between citizens.

Syrian opposition forces and civilians take control of Aleppo citadel, December 2, 2024. Image: Shutterstock, Mohammad Bash

Reporting on Syria, Post-Assad

I re-entered Syria through the Jordanian border just three days after the regime’s dramatic collapse. There were no border stamps or customs offices — just a few employees who took a picture of my passport and waved me through. This was the same border crossing that, just weeks earlier, had been clogged with long lines of vehicles, thanks to stringent security measures to curb the smuggling of the amphetimine-like drug, Captagon.

That evening, I met with my Reuters colleagues at the five-star Cham Palace Hotel in central Damascus — a scene that brought to mind the Palestine International Hotel in Baghdad after the US-led invasion of Iraq, which became the hub and residence for international journalists reporting on the country. The streets of Damascus were dark, military factions’ mud-coated pickup trucks still roamed the city, shock was etched on people’s faces — but the sounds we heard were pens scratching against paper as hundreds of foreign journalists at the hotel made plans for coverage.

Syria, in those moments, seemed like a black box forced open after it had been sealed shut for 54 years — an experience as overwhelming as it was exhilarating. Previously, we had to piece together investigations from mere drips of information. Now, we had access to millions of documents and hundreds of sites that had once been too dangerous even to mention publicly.

For Hala Nouhad Nasreddine, head of investigations for Daraj Media, and who has worked for years on collaborative investigations on financial corruption in Syria with organizations such as ICIJ and OCCRP, it was a surreal experience: “Every time I remember this moment I ask myself: Did we really enter Syria and work from within security branches?”

“Syria at that moment was a huge container of information within our hands,” she adds. “We used to build investigations on leaked documents or information provided by parties from other countries, like in the Dubai Unlocked project, but it was the tip of the iceberg. Now we have it all, and that’s a once-in-a-lifetime event.”

Our plan at Reuters, though, was to gather as much information as possible because we knew this window of access wouldn’t remain open for long, and would perhaps slam shut before the chaos subsided. (Read Feras Dalatey’s reporting for Reuters on the fall of Assad and Syria’s sectarian violence.)

We began our visits with the General Intelligence Directorate in Damascus. We bypassed the reinforced concrete barriers that once surrounded the security branch, but what was most chilling was the sight of the large, torn portrait of Bashar al-Assad hanging above the entrance — a portrait that had, just days before, instilled fear in anyone who looked at it. Beneath it was a shattered image of his father, Hafez al-Assad, who ruled the country with an iron fist for three decades.

Mohammad Bassiki, co-founder of Syrian Investigative Reporters for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ), explains that he didn’t come to Syria with a clear investigative idea. In fact, several investigations his team was working on were canceled as the situation in Syria changed, but the new reality opened up other kinds of investigations. “Being on the ground gave me a huge advantage over being a journalist working abroad — sometimes under pseudonyms — who goes through a long process to protect sources. I was able to dig up information myself from the piles instead of searching open sources,” Bassiki explains.

Syrians exploring the abandoned Presidential Palace in Damascus on December 9, 2024. Image: Shutterstock, Mohammad Bash

The Challenge of Preserving Documents and Sites

Unfortunately, due to the lack of security controls in those early days, some individuals handled the documents recklessly. Reporters from a major Arab news channel tampered with the documents, filmed them, and then abandoned them in the courtyard of one of the security branches, where they were soaked by rain the following night. A volunteer group painted over the walls of underground cells in another branch — walls that held the memories of disappeared detainees. But the most disappointing incident involved a fixer journalist accompanying a global newspaper team who stole several hard drives from another security facility.

The unrestricted access to these highly classified sites created what could be described as security tourism — allowing untrained individuals to enter these places and repeat such incidents. However, handling these sites requires far more caution than merely taking photos. According to the London-based Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), more than 100,000 people remain disappeared in Assad’s prisons. Their deaths have not been officially recorded, nor were they released when the prisons were opened during the fall of Assad.

This was a historic opportunity to uncover the fate of thousands who had disappeared in Assad’s prisons. The world had long known that the Damascus Military Police headquarters served was the hub from which the bodies of tortured victims were secretly removed, after military defector Colonel Farid al-Madhhan — who was known for years as “Caesar” — fled Syria in 2013 while leaking thousands of photos of torture victims.

I did not miss the chance to go to the police headquarters. Fleeing soldiers had left behind some of their military uniforms and even personal weapons. Assad’s portrait remained intact, so I jokingly asked the guards at the entrance why it had survived. (They laughed.) Inside, I found thousands of personal identification cards, medical reports, and photographs of detainees at the Forensic Evidence Center. Most death certificates cited “heart attack” or “stroke” as the cause of death, despite the horrific signs of torture on the bodies. The most painful detail was that these victims did not have names in those reports — just five-digit numbers, reducing entire lives and stories to mere figures.

Sednaya Prison, north of Damascus, where thousands of Syrians were held and tortured, photographed on December 12, 2024. Image: Shutterstock, Mohammad Bash

It remains unclear why such detailed documentation of these crimes existed, but one way or another, it complicates the work of investigative journalists and researchers. One approach to uncovering victims’ identities involves cross-referencing ground-level reporting with open source investigations. We had the documents, but we also needed to speak with families and local communities in areas frequently mentioned in the records — places known for documented massacres, such as the Tadamun neighborhood in southern Damascus, where the Guardian revealed a gruesome massacre a few years ago. Additionally, satellite imagery could help identify anomalies in the landscape that might indicate mass graves.

However, this work can not be completed without some measure of cooperation from the government. Journalists are not judges or prosecutors; once they find stories or uncover evidence, the government, the judiciary, scientists, and other actors need to do their part in advancing the process. The current administration has yet to show the will for this kind of support. Tadamun, for instance, is a sea of rubble with thousands of human bones scattered across its surface. Bloodstains and brain matter still mark the remaining walls from field executions. Our investigation could identify victim counts, perpetrators, and some identities, but it would remain incomplete without systematic forensic DNA analysis — currently left vulnerable to being tampered with by passersby, despite the area being a fully fledged crime scene.

Assad’s men worked tirelessly to hide or destroy evidence — like the thousands of shredded papers I found outside the General Intelligence Directorate chief’s office or the archives reduced to ashes, collapsing into dust at the slightest breeze. But they could not erase the country itself, which bore witness to their atrocities at every corner.

Nasreddine explains that, after coming back to Lebanon from Syria, she had to take some time off before working on the documents they scanned: “We all knew how notorious the regime was, but it’s much heavier to see by yourself what was going on and hear directly from survivors… It’s beyond imagination.”

Fall of the ‘Giant Wall’

Despite the abundance of information that became available from administrative and military headquarters in the first weeks after the regime collapse, speaking to sources remains fraught with tension and discomfort for two reasons.

The first is the longstanding fear that the notorious security branches have instilled in Syrians about speaking or disclosing information, no matter what kind. This reminds me of the common expression “the walls have ears,” referring to the pervasive intelligence eavesdropping in all aspects of the country. This led one of my sources, despite knowing many useful details, to speak in generalities without mentioning specific names.

The second reason is a law passed by the new administration that makes it illegal to speak to “figures of the former regime,” without specifying who could be part of this group. This has caused many journalists to think twice before making contact. I struggled to convince a former minister to sit in a public place and talk about a topic related to espionage, only for him to come to me wearing a cap and sunglasses, then end the conversation and leave less than a half-hour later without providing any information.

The fall of the “giant wall” that the regime built around watchdog journalism gives SIRAJ co-founder Mohammed Bassiki hope that Syria can transform from a totalitarian state hostile to the press to a free and democratic country — and that journalism will play a crucial role in this next phase of the nation’s history by contributing to increased transparency, assisting in achieving transitional justice, and promoting freedom of information.

“All of this was not possible before the fall of this totalitarian regime, and this is an ambition that I and hundreds of other journalists share,” says Bassiki.

Although the new administration still shows some apprehension about cooperating with journalists, our duty as investigative reporters and watchdogs is to seize this moment to seek answers after years of asking questions.

“There are no direct restrictions yet of press freedom by the new authorities, but we [journalists] will not allow them to take this path again after the price we paid to gain this momentum,” Bassiki says.

I often recall it when I asked a newly appointed state media official about businessmen linked to Assad who were now discussing cooperation with the new leadership. His response was: ‘What business does a media outlet have with these names?’

We have every business with them.