When Match.com launched in 1995 in the pre-app era of chat rooms and dial-up internet, it was the first online dating site. Since then, its parent company, Match Group, has grown into an $8.5 billion global conglomerate that controls half of the global online dating market, which has millions of users worldwide swiping in pursuit of romance on its platforms, which include Tinder, Bumble, Hinge, PlentyofFish, and OKCupid.

The Match Group claims that their apps have been downloaded 750 million times, and its Ipsos-led Relationship Report claims that 40% of all relationships in the US start online. These numbers raise concerns about the long-term implications of having a significant proportion of human connections mediated by digital screens on profit-driven platforms. One principal and immediate concern is user safety — particularly for apps designed to facilitate offline connections.

The UN warned this year that online attacks against women are getting worse and that this trend can influence offline interactions. In 2022, researchers at Brigham Young University published an analysis of more than 3,000 sexual assault cases and observed that “dating-app-facilitated sexual assault” happened faster and was more violent than when the perpetrator met the victim elsewhere.

“It’s a really scary study,” says Emily Elena Dugdale, a Pulitzer Center AI Accountability Fellow and lead reporter for The Dating Apps Reporting Project. Dugdale says that BYU’s research sparked their 18-month investigation into how the Match Group was addressing privacy and security issues and upholding its pledge to “make dating safer.”

In January, Dugdale, who is based in Los Angeles, and Bay Area-based Poynter Fellow Hanisha Harjani published Rape Under Wraps: How Tinder, Hinge and Their Corporate Owner Chose Profits over Safety. This exposé, co-published by the Guardian and The 19th, examined shortcomings in the Match Trust and Safety department’s response to reports of sexually violent users. Journalist Aaron Glantz and Sisi Wei from the nonprofit newsroom The Markup edited the investigation.

“If you are someone who digs into companies and institutions of power, you will probably have a very healthy level of skepticism in general about anything that promises you that you are going to be fine using it or doing things,” says Dugdale. “If you’ve been online for decades, you know that regulating online spaces is not easy.”

Hanisha Harjani (left) and Emily Elena Dugdale (center) investigated failures in the privacy and security protocols on Match’s dating apps, which they found enabled systemic abuse. Aaron Glantz helped edit the exposé. Image: Courtesy of the authors

‘There Is No Real Bouncer’

The investigation reported that, according to internal documents, the company had known since at least 2016 about abusive users on its dating apps but chose to ”leave millions of people in the dark,” despite mounting pressure within and outside the company — including from lawmakers — to address and release accurate information on the problem.

Their investigation opens with the case of Denver-based cardiologist Stephen Matthews, who was convicted in October 2024 and sentenced to 158 years to life in prison for rape, assault, and drugging multiple women he connected with on Hinge. The pair’s reporting found that Match’s overwhelmed rape reporting system enabled Matthews to return to the app and commit further assaults, despite multiple women reporting him. Even after someone filed a police report, they write, the only thing that got him off the company’s dating apps was his arrest.

“If you’re in a bar, and someone’s being creepy to you, you’re going to tell the bartender or the bouncer and that guy is going to get kicked out,” explains Dugdale. “With these apps, the bouncer didn’t work. There is no real bouncer. These people can come back.”

Match Group’s safety policy states that when a user is reported for assault, all accounts associated with that user will be banned from their platforms. Safety measures they list include automatic scans of profiles for “red-flag” language or images, ongoing scans for fraudulent profiles, and manual reviews of suspicious profiles and user-generated reports.

Users can use in-app tools to file reports. The investigation notes that since 2019 users reported for rape and assault on any of its apps are recorded in a central database. According to company sources, by 2022, the system — named Sentinel — was collecting hundreds of incidents every week. A slide from an internal 2021 presentation shown to employees and external safety experts and obtained by the Dating App Reporting Project indicates that the company was unsure just how much to reveal to users.

To find out what the company was doing about reported assaults, the team reviewed hundreds of pages of internal company documents and court records. Because Match Group is a public company, they also had access to SEC filings and investment reports. They also held dozens of interviews with current and former employees and survivors of sexual violence.

The investigation ran parallel to coverage of the Matthews case, which involved locating multiple women he had preyed on and reporting on an ongoing case in Colorado. While these women ultimately declined interviews, a decision the investigative team respected, details from court hearings reported with the assistance of Colorado-based stringer Stephanie Wolf were incorporated.

“It was really important for me not to focus so much on gratuitous descriptions of the actual assaults and the crime. I did not want that to be the focus of the story,” says Dugdale, who collaborated with Harjani to tell the stories of targeted women using court reports, avoiding a sensationalistic approach.

“I wanted readers to have enough information to understand how easy it is for something like this to happen, to understand the fear that people felt, knowing that they couldn’t remember these things that happened to them because they were drugged. There was physical evidence on their bodies that underscores the severity of the abuse.” Attorneys representing the women stated that much of the violence Matthews inflicted could have been avoided.

They also created an investigative data experiment to test whether the company banned users reported for sexual assault. Working with The Markup’s Natasha Uzcátegui-Liggett, they created more than 50 accounts across multiple platforms. They found that while accounts reported for assault were often banned within two days, it wasn’t difficult to create new accounts with the same information or with simple changes to biographical details. In the process, they consulted online guides on getting back on dating apps after a ban.

The investigation asserted that, while the company does have the resources, tools, and investigative procedures to make it harder for bad actors to return to apps, “internal documents show the company has resisted efforts to spread them across its apps, in part because safety protocols could stall corporate growth.”

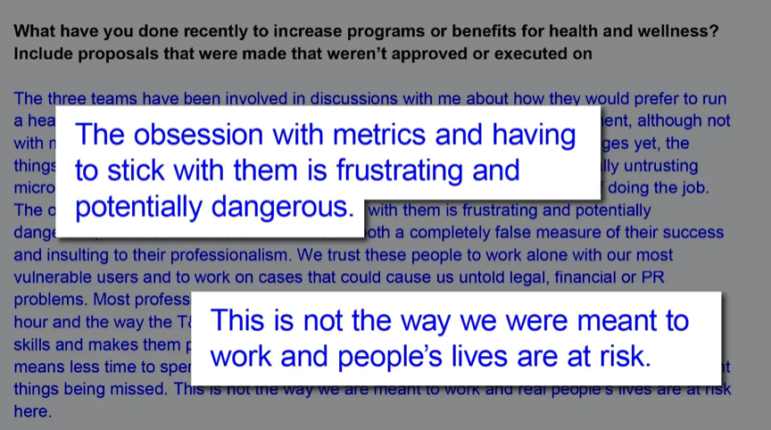

Multiple sources within Match Group revealed that the company’s “obsession with metrics and having to stick with them is frustrating and potentially dangerous.” One source specifically described Match Group’s ongoing pledges to invest in safety as “safety theater.”

The Dating Apps Reporting Project sent Match Group a letter detailing their findings, which issued a short statement in response — not disputing that they had documented harm without sharing the information with the public but defending their safety efforts: “We take every report of misconduct seriously, and vigilantly remove and block accounts that have violated our rules regarding this behavior” and that they are industry leaders in employing “harassment-preventing AI tools, ID verification for profiles and investments in communicating with law enforcement.”

The reporting team uncovered internal Match communications where staff expressed concerns about the company’s growth metrics and the impact that might have on jeopardizing user safety. Image: Screenshot, The Markup

How Safety Systems Are Failing Women

Dugdale’s background as a criminal justice beat reporter honed her investigative skills and informed a journalistic approach that avoided “true crime-like” narratives. She chose instead to demonstrate how systemic failures impacted individuals.

“I wanted to put the onus and focus on the companies that allow these men, primarily, [to harm]. Of course, there are people of all genders who are doing this,” Dugdale explains.

This approach was commended by Dr. Alessia Tranchese, a researcher at the University of Portsmouth who specializes in digital media and sexual violence against women. She praised how the article “starts off with an individual case, without over-sensationalising it to discuss a broader issue… It does not treat it as an isolated incident — which is so common in rape coverage — but looks at the broader structure that supports the violence of men against women.”

Dr. Tranchese told GIJN that “a crucial point for journalists is to see each case of sexual violence as part of a pattern of male abuse towards women, not as a specific case to be addressed, detached from the rest of society.”

Dr. Tong-jin Smith, a media research academic at Free University, Berlin and former journalist, agreed that the backlash against female empowerment as seen on social media is connected to how people interact on dating apps.

“Dating apps, in my mind, are the extension of social media. It comes from the same kind of thinking. Here it commodifies even more,” says Smith, who underscored the importance of investigative journalism in exposing the underlying mechanisms of the digital economy.

“It’s important that people are empowered. That they know what they are doing. That you realize that on the other end there is an actual human being, and that respect, and treating each other with respect is important,” Dr. Smith stated.

Dr. Smith advocates for media literacy training in schools, arguing it could equip young people to better navigate how platform economics, combined with the social pressures of our app-saturated world, can influence their perspectives and actions and make women vulnerable to violence. She emphasizes the crucial role of investigative journalists in covering this issue to explore solutions.

Having an impact that might protect dating app users was a key driver in the investigation. “I’m hopeful we’ll see some real, lasting change down the line,” says Dugdale, adding that she and her team were encouraged by positive feedback from employees at dating app companies and women victimized since the article’s publication. This feedback has re-engaged US lawmakers, raising hopes that increased pressure might influence Match Group’s priorities.

“The wheels of justice do take time,” she adds.