Independent nonprofit media around the globe suddenly find themselves at the center of a perfect storm of at least four new existential threats.

- The sudden, technically illegal hold on USAID foreign assistance funding by the US Trump administration has frozen an estimated $268 million in agreed grants for independent media and the free flow of information in more than 30 countries, including several under repressive regimes — and much more lost for the future — throwing much of the nonprofit watchdog sector into crisis, and potentially leaving numerous reporters, contractors, and accountability projects without pay in the weeks ahead. This is in addition to devastating cuts to the agency’s public health and humanitarian programs around the world. Despite ongoing confusion and many legal challenges, several media grantees and experts told GIJN they regard this important funding as dead.

- The ransacking of USAID systems by unaccountable private sector agents poses an urgent data security threat to journalists, according to development experts. They have warned that contact details of thousands of human rights defenders, media support actors, and journalists involved in US-funded projects in the past decades, as well as information on what they do and how they work, has fallen into hostile hands.

- The USAID freeze and accompanying US administration social media attacks on officials and beneficiaries has fueled new threats and proposed criminal investigations by enemies of independent media in repressive nations. It has also amplified public smears against courageous networks holding bad actors accountable in the public interest.

- The freeze further disrupts an already fractured sustainability environment in which some funders have slowly exited the sector, and in which policy changes at major social media and tech companies have suppressed distribution, promoted misinformation, and enabled harassment of independent media and its sources. The risk of self-censorship to lure future funding is yet another allied threat in this bully landscape.

Some of the gravest immediate threats are being faced by exiled outlets and independent media in places such as Ukraine, Cameroon, and throughout Central America.

For example, Ukraine’s Slidstvo.info, an award-winning independent investigative agency, lost 80% of its funding in a single day in January, as its two respected intermediary funders reportedly confessed their own shock, and reluctantly but firmly warned the organization to immediately halt operations on the USAID money they disburse — including any use of grant money already in the outlet’s account.

“It is a nightmare for us,” says Anna Babinets, director and editor-in-chief of Slidstvo. “The funding was running till the middle of next year, and it stopped just in one day.” She revealed that the outlet would nevertheless continue to produce current investigations in the weeks ahead — including a major war crimes exposé and a real estate corruption scoop — and use modest savings to cover essential costs for the next two months, while seeking emergency alternate funding daily and cutting all travel costs by reporters, except for frontline war reporting.

The independent Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) was likewise forced to lay off 43 valued reporters and staff, according to its co-founder, Drew Sullivan, after losing 29% of its USAID-sourced funding overnight. “We are determined to stay in the fight and keep reporting on organized crime and the corrupt who enable and benefit from it. But it’s getting harder and we need help,” Sullivan wrote on LinkedIn.

The abrupt nature of the funding shutdown also put reporters’ safety in jeopardy. “This was without any warning, so people working in difficult environments like Ecuador — people with teams and families, who are risking their lives to uncover money laundering, human trafficking; illegal exports — all of a sudden they have no funding,” explains Maria Teresa Ronderos, co-founder of the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (El CLIP).

“The worst thing for my friends and partners is that this has given a lot of force to the local enemies of media, whether government or organized crime,” she adds, pointing to heightened risks in countries such as El Salvador and Guatemala. “Some countries are proposing to investigate the media who were receiving money from USAID, because [they say] ‘even the US government is saying they are propagandists or spies or terrorists.’”

In addition, some media grantee organizations have reported receiving letters from the US government that justify individual grant suspensions because of their “diversity, equity, and inclusion” practices.

Community Rallies with Solidarity and Hope

While various legal challenges in the US could succeed in unfreezing some USAID grants — and many other non-US government funders remain interested in supporting independent journalism and the democratic societies they preserve — the sustainability and security situation is undeniably urgent. However, emergency meetings and actions in recent days have revealed powerful bonds within the community, as well as useful tips and resources, and striking claims that the crisis itself could prove to be the ultimate rallying point for solutions for vulnerable business models. As Brant Houston, chair of GIJN’s Board of Directors, points out: “One of our best arguments for alternative funding is this attack on what we do.”

GIJN noted in a formal statement by its Board of Directors: “The attack on these newsrooms and USAID funding by autocrats and oligarchs demonstrates how effective the newsrooms have been in their coverage. … To cut off these funds means investigative newsrooms, such as those in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and the Pacific Islands will be stymied or completely unable to continue this invaluable reporting.”

The board also emphasized that “our member organizations have shown repeatedly that their reporting has been independent and has come under no pressure from USAID officials or staff — and the results of their investigations show that they report without fear or favor.”

In a survey of reactions and sustainability ideas from key members of the investigative community this week, GIJN has heard uniform voices of solidarity, and numerous creative strategies that offer pathways of hope to survive this crisis.

This cooperative spirit has included media networks and journalism support organizations rallying to provide vulnerable outlets with clarity on the wildly changing funding and legal situation, and emergency calls for civil society solidarity and support from donors.

GIJN has also heard from several outlets with modest budgets, such as El CLIP, stepping up to help partners and peer organizations affected by the USAID freeze with information, grant support, and minor costs assistance — and GIJN will continue its efforts to support investigative journalists around the world by providing training, sharing best practices and information, producing guides, and through the power of its community exchange knowledge around methods, tools, and technology to go after abuses of power and lack of accountability.

A press freedom protest in Istanbul, Turkey. Image: Shutterstock

Some of the emergency responses and resources for affected newsrooms include the actions below

- In addition to live GFMD resources on the crisis, GFMD has prepared a letter endorsed by 97 press freedom organizations with urgent calls for independent media support to donors and democratic governments in key areas. Newsrooms that would like to share this letter privately with potential donors may access it by writing to [email protected].

- One useful resource for tracking the legal challenges to those actions, including attacks on USAID, can be found at Just Security’s Litigation Tracker tool, which is constantly updated. In a briefing to GFMD members on February 7, one attorney revealed the ongoing legal confusion: “Two courts have ruled that the freezing of funding is illegal… the suspension of your grants seems to be nullified by these court rulings, and likely by the next ruling. But we can’t say that if this government has an order to resume funding that it will resume.”

- Some independent organizations mobilized reader support for smaller peer organizations, such as Kyiv Independent’s GoFundMe campaign to raise emergency cash for three affected Ukraine outlets. It raised $53,000 in the first week. Independent media seeking legal guidance on emergency sustainability options — such as joint ventures, bridge loans, understanding contract implications, or registering in alternative jurisdictions — can apply to be connected with pro bono legal assistance using the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s TrustLaw service.

- Survey data on remaining financial resources for affected nonprofits can be visualized via the Global Aid Freeze Tracker. A new resource from Davis Wright Tremaine LLP also offers advice for the most-affected newsrooms.

- If you feel secure, be very public and vocal about the value and impact of your independent journalism for your region and the world in social media and publications.

- Funding experts also noted that recent court decisions could theoretically cause the release of US media funding — adding that “nothing can be lost” in asking intermediaries to reopen grants – and offered the following “immediate action checklist” (while noting it was not legal advice:) Note all instructions and deadlines from any stop work orders carefully, and communicate promptly with the CO/AO; identify and explain essential costs; track and preserve records of all expenditures for potential reimbursement, including offline copies; provide clear communications on paused projects with staff and contractors; and build contingency plans, including sub-contract modifications and emergency alternate funding options. Experts noted that any proposals or reports to the US government featuring phrases such as “diversity, equity, and inclusion” would likely be immediately rejected.

Independent media in Ukraine and the Balkans have been among the hardest-hit, with several nonprofits forced to supplement their funding with reader donations, help from peer outlets, and even appeals for corporate donations, in the case of Bihus.info, which lost two-thirds of its funding in the freeze.

For Anna Babinets at Slidstvo, the immediate priority is to “find a small amount of money” to complete and publish several live investigations.

“We are soon to publish an important story about war crimes committed by Russians, where we obtained proof of those crimes; we also have corruption stories, involving wrongdoing by officials,” she said. “I can’t just stop them.”

Babinets said her team briefly considered switching to advertising revenue, but rejected that option as a potential future conflict of interest.

“We have some savings for maybe a couple of months, we have some monetization from our Youtube content, and we have some contributions from our audience,” she added.

While some outlets in Africa have been hard-hit, such as DataCameroon, Beauregard Tromp, convenor of the African Investigative Journalism Conference (AIJC), declared confidence that the sector on the continent, overall, would not only weather the storm, but continue to produce outstanding investigations that rival the quality of well-resourced projects in the West.

Tromp revealed that in-process USAID grants totaling US$28 million for the promotion of investigative journalism in Southern, East, and West Africa, respectively, had been frozen. He noted that another disappointing aspect of the USAID cuts was that its grant assessment processes in Africa had recently improved and grown more responsive to local needs.

“It’s a terrible shame what’s happened,” he says. “But one good thing about African media is we’ve had to survive under exceptionally trying conditions in the past, and we are used to struggling.”

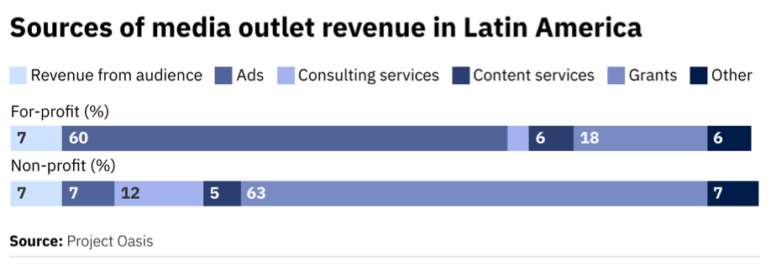

There are many other potential sources of funds for independent media, from high net-worth individuals to charitable foundations and multilateral institutions. In fact, a recent Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism report on 32 independent media outlets in 16 Latin American countries — one of the least diverse funding environments — found that 70 separate institutional donors supported those outlets. The report did stress the urgent need for further diversification of funding sources.

The 2024 Reuters Institute report ‘Safeguarding Independent Journalism in Latin America’ noted Project Oasis data, which found commercial digital outlets in Latin America rely mostly on advertising, while nonprofit independent media rely heavily on grants. Image: Graphic, Reuters Institute

Still, OCCRP’s Drew Sullivan underlined the importance of USAID funding to his organization’s network in his post: “This money did not only fund groundbreaking, prize-winning collaborative journalism but it also trained young investigative reporters to expose wrongdoing. It’s money that kept journalists safe from physical and digital attacks and supported those in exile who continued to report on crooks and dictators back in their home countries.”

Diversifying Funding and Pooling Resources

Going forward, the consistent message heard in the past few weeks was: pool your resources and diversity your funding sources.

Network leaders said it was still too early for many organizations to commit to new sustainability strategies, as they grappled with the legal implications of grants, employee contracts, and court challenges. Due to the sudden nature of the funding freeze, Ronderos says: “People are just starting to think about what other ways they can raise money.”

Funding experts also highlighted the fact that the current mature, collaborative watchdog journalism community represents a huge opportunity for foundations. Directly funding operations of these pre-existing accountability news outlets and networks can have immediate public interest benefits. For instance, AIJC’s Tromp notes that the International Fund for Public Interest Media created an innovative model that combines philanthropic, government and, yes, corporate funds, which are then independently disbursed to media outlets in a way that preserves their editorial independence.

However, veteran founders and editors suggested that many affected newsrooms should consider some of the following creative — and sometimes controversial — sustainability strategies:

- Try converting project grants into general funding. “Pick up the phone and ask your donors for flexibility… so you don’t have to use [funds] for a specific project, because you need it for salaries and general support to achieve any or all of your mutual goals,” Ronderos urges. “See if they are willing to give a little more money; maybe do a festival selling coffee: be creative about new ways of earning money for the emergency these next few months.” See GFMD’s fundraising guide, here, and GIJN’s recent guide, here.

- Seek free advice on bridge loans, or re-registering in funding-friendly jurisdictions. Independent media can seek free legal guidance on sustainability options by applying to the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s TrustLaw service.

- Consider merged newsrooms. “In many cases, there are 20 independent media outlets in one country. They really should consider joining forces and having one or two outlets that are stronger and can more easily get funding, and benefit from the economies of scale,” Ronderos advises. “This extreme attitude of ‘I will do my own thing because only I know how to cover this issue’: that position could be shaken right now. Look to team up and produce good journalism with different ideas; not the same idea.”

- Get wealthy Western donors to mobilize their Global South friends. “Rich guys in the US give money to the media because they know it’s important, and they have a bunch of rich friends from Brazil and Argentina and Colombia,” notes Ronderos. “They could do a lot, and say, ‘Guys, let’s come together, and let’s fund media left out of the USAID package together.’”

- Consider changes to your corporate funding policy. “There is a lot of corporate funding out there that is not necessarily unethical; not necessarily a conflict,” Ronderos explains. Echoing AIJC’s Tromp, Ronderos says the IFPIM model, which includes ethical corporate funding, was an important model for established journalism teams. “They created these amazing vehicles a few years ago — an initiative involving Luminate — so they would create a fund that could receive money from corporations or from whomever, and they would then fund media outlets all over the world without affecting their independence.”

Experts noted that some newsrooms had sought US government funding in recent years due to changes of direction in some foundations, and the closure of others, but that hope remained within the community that some of this older support might return to the sector, albeit in different forms. AIJC’s Tromp concludes: “Bottom line: outlets will just have to diversify their funding and income streams.”

Some members from the community also worry about new data security and harassment threats. One development expert says: “We’ve seen data about support projects being shared on Twitter; we’ve seen hit pieces on GFMD members and others, and we can only expect this to continue. We’ve seen Azerbaijan, Hungary, Belarus, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and others welcoming USAID’s disbanding, and the narratives around enemies of the state; traitors; spies raking in this money already in circulation. ” Still, Tromp noted that the information typically shared with state funders or nonprofit grantors is relatively benign, and not likely to present a safety risk if made public.

Despite these looming funding challenges, AIJC’s Tromp, like many others in the investigative journalism community interviewed for this story, remains focused on persevering through this crisis. “We’re journalists who have had to pivot like crazy before and we have to make it work,” he says. “We don’t have time for ‘Oh, woe is me’ — we don’t have time for that bullshit. We have abuses to investigate.”