At the end of 2021, months before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began, Russia started to gather troops and military equipment at the border.

At Texty, an award-winning Ukrainian data journalism organization, the team knew this was no exercise — the Kremlin had almost certainly decided to strike.

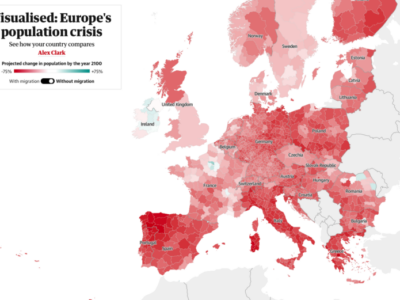

Clues were scattered across the data. Their examination of Moscow’s propaganda had revealed leading Russian websites were suddenly using the word ‘invasion’ much more often in news items about Ukraine. Fearing what might happen next, the team created an interactive map enabling readers to monitor Russian military bases and shared another to help residents locate the nearest underground shelters in the capital Kyiv.

Still, the attack in February 2022 came as a shock. “It was hard to believe,” says Yevhenia Drozdova, Texty’s head of data journalism who leads the team’s effort to visualize and make sense of the ongoing war.

In the three years since, the team has been doing their part to investigate the impact of the war on Ukraine and to counter the Kremlin’s propaganda machine.

Combating false and misleading narratives has become an integral part of Texty’s work. In 2020, the outlet won the Sigma award for an innovative platform tracking Moscow’s large-scale disinformation operations. In a previous project, Texty untangled a complex network of pro-Kremlin trolls on Facebook that were amplifying conspiracy theories. These days, they have entire verticals dedicated to #Infowar and #Disinformation.

These are the types of stories that illustrate the outlet’s mission, says Texty’s editor-in-chief, Roman Kulchynsky, who co-founded the publication with his colleague Anatoliy Bondarenko.

“We don’t publish quick news. We try to understand and analyze what happened in reality,” he says. “To make difficult things clear.”

Peacetime Concept Becomes a Voice of Defiance

It was 15 years ago that the co-founders realized the potential of data-driven reporting, and the power of merging traditional and digital journalism.

Texty — official name Texty.org.ua — slowly evolved from Ukraine’s first center for data journalism into an internationally renowned media outlet. Today its team is made up of a dozen full-time staff members and three interns. It was accepted as a GIJN member in 2017.

Bondarenko, whose programming skills helped spark a new approach to news coverage, left to join the Ukrainian army soon after Russia invaded. But between the sounds of air raid sirens, recurring blackouts, and the constant threat of drones and missiles, his former colleagues continue to work in extraordinary circumstances.

“Three years in a row, we don’t sleep properly. Most of the night, you’re staring at your smartphone,” always assessing if your city, or district, could come under Russian attack, Drozdova says. “[The fact] that we’re tired and exhausted doesn’t mean we want to put our hands down and raise white flags.”

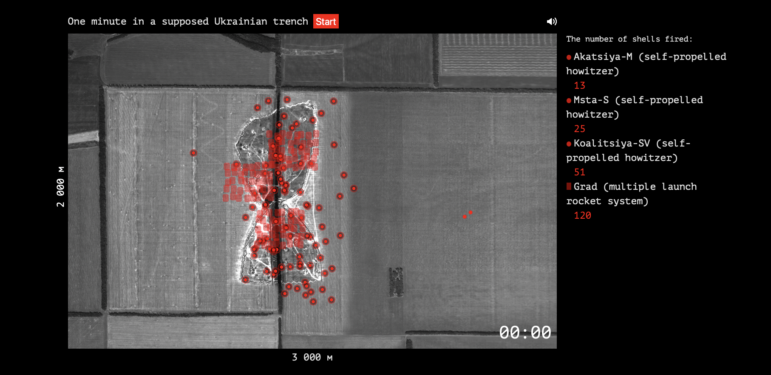

Wartime journalism has presented Texty with unforeseen challenges, but also invaluable opportunities to push the boundaries of data visualization. A game released a week before the invasion helped readers learn to distinguish Ukrainian from Russian tanks. Satellite images, human stories, and manually collected information also enabled the team to paint a complex picture of the war’s impact and a soldier’s life in the trenches.

“Data alone usually doesn’t work well. You also need to explain to the reader what the data means,” says Alberto Cairo, the Knight Chair in Data Visualization at the University of Miami and a leading expert on data journalism, who wrote a chapter about Bondarenko in one of his books.

He says Texty – like organizations such as ProPublica in the US and Agência Lupa in Brazil — found its strength in a form of investigative reporting “from a principled stance.”

“I sympathize and empathize with the struggles and the pain sometimes, the amount of time and effort that projects may take. And the drive to put them out no matter what. That’s what a true journalist does,” he adds.

But the stakes of truth-telling can also be deeply personal. Kulchynsky understands that better than anyone. He lost his best friend Oleh Sikalo on the battlefield.

“Someone from our mutual friends told me that ‘Oleh went missing.’ I contacted his wife, who said there was almost no chance he had survived,” recalls Kulchynsky.

A journalist to the core, in the face of tragedy he tried to find out what happened by investigating the case, reconstructing Sikalo’s last moments before he was declared missing. “Thanks to his wife, we managed to find eyewitnesses who agreed to speak. It’s very sad but a fairly typical story in this war,” he says.

Backlash and Smear Campaigns

When US President Donald Trump was sworn in for the second time in January, Kulchynsky and his colleagues had an ominous feeling of inevitability. A major shift in global politics was about to happen — but this time, Texty found itself at the center of the storm.

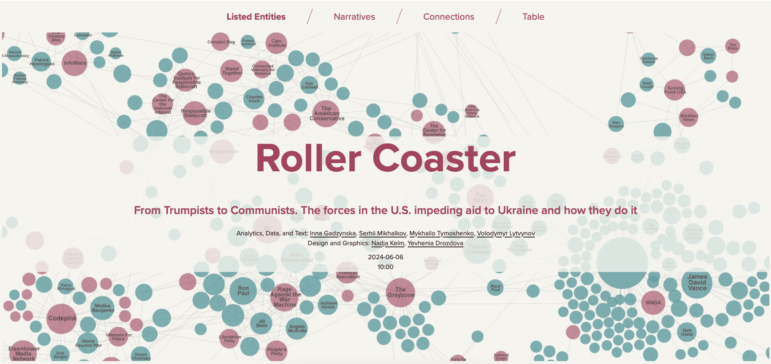

In June 2024, months before Trump had won reelection, Texty published a deep dive on the US lawmakers, journalists, and think-tanks advocating for the US to stop supporting Ukraine’s defense efforts, highlighting the “prominent individuals and common arguments [they use] that often mirror Kremlin propaganda.” The investigation examined the connections between various opponents of US aid to Ukraine, a motley crew that included everyone from Trump supporters to “communists.”

Before Trump was elected, the team at Texty dived into the people publicly pronouncing scepticism regarding aid to Ukraine. They found people across the political spectrum. Image: Screenshot, Texty

After publishing the story, Texty faced a series of withering attacks and threats, and an immense backlash from US conservative outlets, the ultra-right, and left-wing activists. The outlet was falsely accused of creating a “hate list” of US citizens. Twitter/X-owner Elon Musk, who was donating hundreds of millions of dollars to Trump’s campaign and is now an unofficial White House senior advisor, echoed calls to strip Texty of any US donor support and declare the website a terrorist organization. The team refuted the claims, calling them “an attack on freedom of speech,” but the controversy left a lasting impact on its operations.

“One of our donors, who operated with US budget funds, delayed the already-approved grant extension and later canceled it altogether,” Kulchynsky says. “All negotiations for new grants from organizations managing US budget funds came to a halt. We faced the risk of being left without any funding and having to radically downsize our team. This had a demoralizing effect on our staff, and several people resigned.”

Earlier this month, Texty saw another online pile-on — this time in relation to an article the outlet published about elections in Romania. Once again, the outlet warned that the “attack has signs of coordinated actions that are part of a campaign against Ukraine.”

“It was incredibly bizarre… [However] It’s important to respond to every such case and not be afraid of being drowned out,” Kulchynsky says.

Surviving Funding Challenges

The co-founders in a previous donations drive, in which they pointed out that “high-quality journalism is one of the important institutions of the modern state.” Image: Screenshot, Texty

The 2024 controversy pushed Texty to rethink its funding strategy. The outlet had always relied on grants, but was suddenly forced to diversify its donors and also explore other opportunities.

“At the moment, about 70% of our budget is covered by a grant from one of the European foundations, and around 10% comes from reader donations,” Kulchynsky explains. In January, after the US State Department suspended its support for media organizations around the world, the team lost 20% of their budget, which had been covered by a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). “We are currently looking for a replacement,” he says. (In March, a US district court judge reversed the Trump administration’s NED cuts, and so far more than half of its Congressionally-appropriated funding has been restored — but the long-term status of NED grants remains unclear.)

Texty now needs to establish a new financial model to secure a more sustainable future and retain its journalists. According to Kulchynsky, the next year and a half will be crucial. Advertising revenue in Ukraine can’t cover the costs of high-quality data-driven reporting. And many professionals with specialized skills would prefer to work for IT companies, where salaries are generally higher.

But the team at Texty has another idea — using the organization’s trademark storytelling approach to generate additional profit.

“In this situation, the only viable alternative to donor funding is offering data analysis and interactive visualization services — our area of expertise — to other organizations. These products will be delivered to clients and not published on our website,” Kulchynsky explains, but adds that this approach has its risks.

“Working on such projects is often tedious, requiring extensive client coordination, which can demotivate our specialists, who would prefer to focus solely on journalism.”

Journalism in an Uncertain World

For most organizations, achieving financial security would be enough to keep the team together. But as the war goes on, Ukrainian news outlets are confronted with the most existential of questions — should journalists continue their work, or be involved in the physical fighting for the defense of Ukraine?

“I never thought about quitting journalism. But sometimes I’m forced to think there could come a time when I need to join the armed forces,” Drozdova says. “We won’t have data journalism in Ukraine if we don’t have Ukraine.”

A ceasefire deal between Kyiv and Moscow could bring the war closer to its end. But even if there is an end to the fighting, Ukraine will likely face years of vast rebuilding efforts and potential political instability.

With authoritarian leaders on the rise across the democratic world, peace alone doesn’t guarantee media outlets the freedom to hold power to account.

The team has also used data to explore the cultural impact of war. The Stolen Treasures report is a piece that explores the 110,000 Ukrainian artifacts found in two Russian museums. It was nominated for a 2024 European Press Prize in the innovation category. Image: Screenshot

Cairo praises journalists like those at Texty, and those working in other challenging situations, who are willing to risk everything to work in the public interest.

“I wish to believe that if I were in the same circumstances, I would do the same thing. But I don’t know whether I would have the courage,” he says. “Would I change the way that I do things under a different regime, under a different type of government? I wish to believe that I would keep doing what I do just because my personality is a little bit rebellious in that sense. But I don’t know whether I would do it. And so I admire that.”

In their efforts to document the war and investigate the fabric of Ukrainian society, Texty will continue experimenting with new tools and technologies, merging them with traditional journalism genres. Drozdova remains optimistic about the future as her outlet aims to stay at the forefront of ambitious data-driven reporting.

“I hope we will be the leaders in Ukraine in this sphere. We try to share our knowledge and our experience. And I dream of a data journalism conference in Ukraine, probably sometime after the war,” she says.