Editor’s Note: In their responses, the Danish authorities pushed back on specific parts of our findings. Where relevant, their responses are reflected in the full text of the report.

For more than two years, Amnesty International’s Algorithmic Accountability Lab (AAL) has led a sweeping probe into Udbetaling Danmark (UDK), Denmark’s welfare agency. The findings reveal troubling patterns that echo broader concerns across Europe: discriminatory practices of states targeting people seeking benefits, casting a shadow over the very systems that are meant to protect them.

The investigation, Coded Injustice: Surveillance and Discrimination in Denmark’s Automated Welfare State, exposes yet another disturbing experiment by European governments in their relentless pursuit of a “data-driven” state. Across the region, through artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning systems, authorities tighten their grip on migration, enforce border policies, and seek to detect social benefits fraud. Ultimately, however, these systems expand a system of insidious surveillance that risks discriminating against people with disabilities, marginalized racial groups, migrants, and refugees alike.

Denmark is known for having a trustworthy and generous welfare system, with the government spending 26% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) on welfare. Little attention has been paid, however, to how the country’s push for digitization — particularly the implementation of algorithms and AI to purportedly identify social benefits fraud and flag people for further investigations — could lead to discriminatory outcomes, further marginalizing vulnerable groups.

Even less is understood about the harmful psychological toll on those wrongly accused or subjected to surveillance by these vast systems.

Those we interviewed, especially individuals with disabilities, emphasized that being subjected to relentless surveillance just to prove they deserve to receive their benefits is a deeply stressful experience that profoundly affects their mental health. The chairperson of the Social and Labor Market Policy Committee at Dansk Handicap Foundation highlighted that people with disabilities who are constantly interrogated by case workers often feel depressed, and say constant scrutiny is “eating” away at them.

Describing the terror of being investigated for benefits fraud, another interviewee told Amnesty International: “[It is like] sitting at the end of the gun. We are always afraid. [It is as] if the gun is [always] pointing at us.”

Yet this is just the tip of the iceberg of what we found.

Arbitrary Decisions

Denmark has several social security schemes, particularly related to pensions and childcare, which provide supplementary payments to people that are single. In the quest to identify social benefits fraud, the authorities deploy the Really Single algorithm in an attempt to predict a person’s family or relationship status.

One of the parameters employed by the Really Single fraud control algorithm includes “unusual” or “atypical” living patterns or family arrangements. The law, however, lacks clarity about how these terms are defined, leaving the door open for arbitrary decision-making. As a result, the algorithm risks disproportionately targeting beneficiaries whose circumstances diverge significantly from the prevailing norm in Danish society, such as those who have more than two children, live in a multi-generational household (a common arrangement among migrant communities), or older adults accompanied by others.

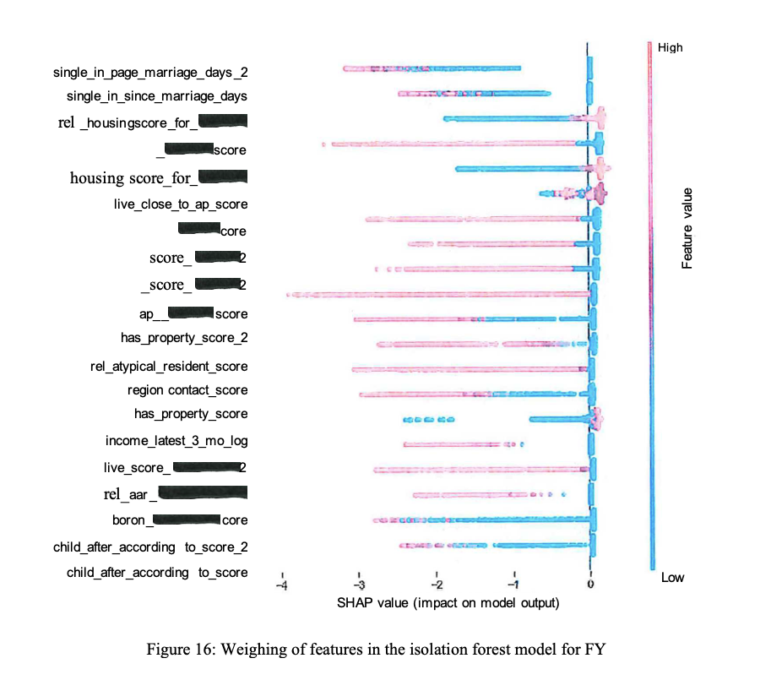

SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) values for the “Really Single” model. SHAP values were developed in AI research to improve the explainability of algorithmic outputs and provide an indication of the importance, or ‘weighting’, of each input to the model. Documentation shows that UDK generates multiple inputs related to housing and residency (for example “housing score” and “rel atypical resident score”), which are included in the algorithm and appear to be heavily weighted, significantly impacting the prediction. Image: Courtesy of Amnesty Tech

The parameter of “foreign affiliation” is also embedded in the architecture of UDK’s algorithms designed to detect social benefits fraud among people claiming pensions and child benefits. The algorithm known as Model Abroad generates a score reflecting a beneficiary’s “foreign affiliation” by assessing an individual’s ties to non-EEA countries. This approach, however, discriminates against people based on grounds such as national origin, as these parameters disproportionately target traits more prevalent amongst groups outside what the system defines as the Danish norm.

These algorithmic models are powered by UDK’s extensive collection and integration of large amounts of personal data from public databases. This data includes details that could serve as proxies for an individual’s race, ethnicity, health, disabilities, or sexual orientation. Data from social media activity is also used in fraud investigations concerning social benefits, further encroaching on personal privacy.

The Danish government has delegated the distribution of benefits to ATP, Denmark’s largest pension and processing company. ATP is responsible for designing the fraud control components of UDK’s Joint Data Unit. In developing its algorithmic models, ATP has partnered with multinational corporations including NNIT, which develops fraud control algorithms based on ATP’s specifications. We reached out to NNIT, but the company did not provide further information about its contractual arrangements with UDK and ATP, citing confidentiality obligations. NNIT also did not disclose information about any human rights due diligence it conducted before entering into its agreement with UDK and ATP.

Three Stages of Research

In our research, we took a socio-technical approach to analyzing Denmark’s welfare systems, carried out in three stages between May 2022 and April 2024. The research also draws on existing published reports about UDK’s fraud control algorithms by various organizations, including the Danish Institute for Human Rights, GIJN member Lighthouse Reports, and Algorithm Watch.

During the first stage, between May 2022 and April 2023, Amnesty International conducted desk-based research to investigate whether the fraud control practices at the Danish welfare agency raised important human rights concerns. We reviewed relevant secondary literature, including reports, articles, and documents detailing the laws governing the UDK and social benefits in Denmark. We reviewed documents on the agency’s fraud control algorithms provided to us by Lighthouse Reports.

During this period and beyond, we met with journalists from Lighthouse Reports and Politiken, both of whom had previously investigated UDK’s data and fraud control practices.

We also conducted searches on the Danish Business Authority’s website to gather information on private sector companies collaborating with the welfare agency to distribute benefits and design its fraud control algorithms. We conducted detailed searches on ATP, the company that manages UDK’s operations and oversees the development of its fraud control algorithms, as well as NNIT.

Extensive Interviews

From September 2023 to January 2024, we entered the second stage of our investigation. During this time, we conducted a total of 34 interviews, both online and in-person, with Danish government officials, parliamentarians, academics, journalists, and impacted individuals, and groups. Additionally, we reviewed a presentation on the UDK system during an in-person interview with the project team at their office in January 2024.

We also held two focus group discussions with impacted groups, comprising individuals living in Copenhagen, Syddanmark, and Jutland. These discussions were carried out in partnership with the Dansk Handicap Foundation.

Additionally, we interviewed six women who receive benefits that originally arrived in Denmark as refugees but are now either registered citizens or hold residency cards. Of these women, two are originally from Syria, three are from Iraq, and one is from Lebanon. Three of the women are over 50 years old while the other three are between 35 to 45 years of age. We recruited these participants in partnership with Mino Danmark. We also interviewed community leaders from local and on-the-ground civil society groups.

Freedom of Information Requests

The third stage involved building a holistic understanding of the UDK system’s inner workings, including its technical makeup, governance framework, the rationale behind its algorithms, and the key actors involved. To achieve this, we filed numerous freedom of information (FOI) requests with national and local employment and fraud control agencies.

Technical evaluations are essential for assessing algorithmic systems. Ideally, these analyses rely on full access to documentation, code, and data. Some level of scrutiny, however, can also be conducted with access to only one or two of these elements.

UDK provided Amnesty International with redacted documentation on the design of certain algorithmic systems, but consistently rejected our requests for a collaborative audit, refusing to provide full access to the code and data used in their fraud detection algorithms.

When questioned on the matter, UDK justified their lack of transparency by saying that the data we were asking for was too sensitive. They also argued that revealing information about the algorithmic models would give fraudsters too much insight into how UDK controls benefit distribution, potentially enabling them to exploit the system.

In addition, through further FOI requests, we asked UDK to provide demographic data and outcomes for people who have been subjected to their algorithmic models, in order to examine whether these systems, for which we had documentation, demonstrated either direct or indirect discrimination. UDK denied our request, saying they did not possess the demographic data requested, and that information on cases classified as high-risk is consistently overwritten, meaning no historical data is saved.

The Danish welfare agency also stated that they could not provide demographic data on the risk classifications assigned to people by the algorithms, asserting that it does not hold this data. While the requested data is highly sensitive, the lack of access to non-privacy-violating demographic statistics makes it extremely difficult to conduct essential bias and fairness testing.

Investigative Takeaways

Although we could not gain full access to technical documents, we have developed an understanding of UDK’s practices based on the evidence gathered. UDK’s failure to provide us with adequate documentation of its maternity, child, and pension models highlights the persistent challenges faced by human rights investigators and journalists working to ensure algorithmic accountability — particularly concerning fraud control systems used by public authorities.

Identifying individuals willing to share their experiences of UDK’s fraud investigations was difficult due to a widespread fear of reprisals from authorities for participating in the research. Nevertheless, this research was made possible due to the participation of numerous partners and collaborators willing to speak up about the Danish welfare agency’s systems.

Socio-technical investigations are essential for investigative journalists and human rights advocates working to uncover how AI systems, when deployed in the public sector, can entrench or exacerbate ongoing human rights abuses against groups that are already marginalized or dehumanized. Technology cannot be divorced from the institutions that produce and deploy it. In the case of Denmark, we prioritized the human experience and individual stories, which ensured that we captured the real impact felt by those who are constantly targeted.