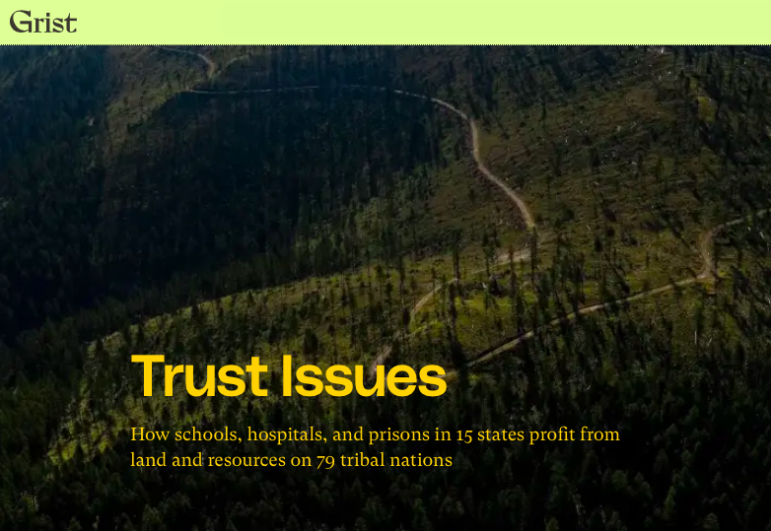

Overlooking St. Mary’s Lake on the Flathead Reservation, in western Montana, the mountainous terrain is interrupted by a clearing of trees from state-managed logging. The 640-acre cut of land contrasts starkly to the neighboring forests, where tribally managed timber operations hold fidelity to the ecological landscape, mimicking fire scars or the natural contours of watershed divides.

This is state trust land, granted to the states by the US Congress upon joining the Union. However, it is rooted in a controversial history of land dispossession where the US came to agreements with Indigenous nations to carve chunks of reservation land for generating revenue. More than 100 million acres of which historically belonged to Native American tribes.

State trust land like this is used by the federal government to generate income to fund schools, jails, and other public institutions, and this parcel is just one small piece of more than 100,000 acres of state trust land across the Flathead Indian Reservation.

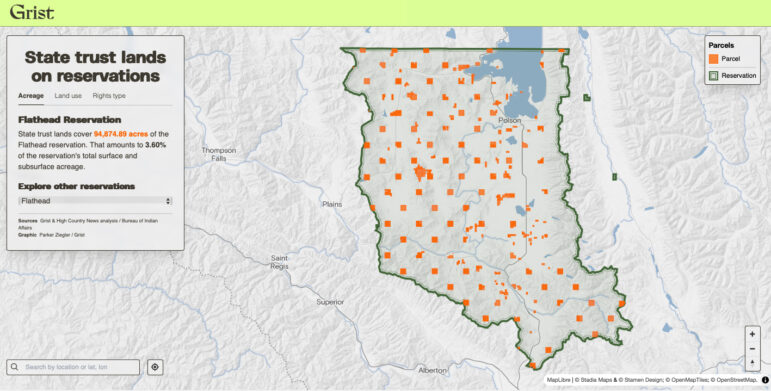

A recent investigation by Grist, a nonprofit independent media outlet, and High Country News, a news organization covering the western US, uncovered the extent of state trust land on Indigenous reservations. A team of reporters and data and visualization journalists spent seven months exploring trust lands data and original treaties in tribal areas to map the historic land grab that has occurred at the behest of the federal government.

The investigation found two million acres across 79 reservations in 15 states are now state trust land. These lands, often leased for oil and gas extraction, timber harvesting, and grazing, underscore a troubling reality: Indigenous lands have long funded non-Indigenous public institutions.

Historical Roots of State Trust Land

Allotment policies in the 19th and 20th centuries saw a checkerboard pattern of land ownership on reservations, with land divvied up among individual tribal members, non-Indigenous owners, and the federal government.

In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act, or so-called Dawes Act, which mandated the distribution of reservation land to individual owners, in an attempt to encourage the adoption of “western” farming practices among Indigenous tribes. Through this process, roughly 90 million acres of Indigenous land was transitioned into non-Indigenous hands.

Now, millions of acres of land — both surface and subsurface — remain under state control, creating a checkerboard of parcels within Indigenous reservation boundaries. The social and economic consequences of this arrangement continue to this day, with tribes vying for sovereignty over their lands.

Tristan Ahtone, editor at large at Grist, told GIJN that he hopes the investigation will give tribes the information they need to regain sovereignty over their ancestral lands.

“I come from a tradition of people who have not been a part of the United States, have resisted the United States, have been enemies or arrested or imprisoned by the United States. So I don’t think my reason for doing journalism or doing this kind of work is for a stronger American democracy. It’s working to serve Indigenous self-determination and sovereignty. This is information and data that tribal nations can use — look at the map and do what they need to do right now,” Ahtone explains.

Building on an Existing Database

The final investigation, Trust Issues, built upon existing data collection by Grist, whose previous collaborations with High Country News on so-called Land Grab Universities exposed how the Morrill Act of 1862 granted expropriated Indigenous land to states in order to fund universities.

For this latest exposé, the team went further, combining two datasets — one on state trust lands and the other on federal records of original treaty areas in tribal lands. Original treaty data provides a snapshot in time on how the US was mapping out particular areas during the treaty-making process in negotiations and/or warfare with tribes.

Ahtone told GIJN about the difficulties of attempting to map treaty areas with state trust land data given that treaty data came from federal, state, and tribal sources. However, their analysis found the data did not neatly line up with some ownership claims and borders, and so it is not entirely accurate.

“It’s sort of a nightmare to figure out who is who because those treaties are being made with only two or three groups at a time. But it does give us a stable dataset to understand at least how the United States was expanding treaty by treaty into the West. So we can use that to make those connections. So to some degree, that’s pretty easy and the federal government already has that digitized.”

“The issue was of adding another data level of the state trust lands data,” he adds.

Grist data reporter Maria Parazo Rose went to each state’s REST server to download and scrape data on all state trust lands. “As far as I understand, basically every single one of those datasets that we pulled down from all 15 states was in a different form. Maria pulled them all down and then more or less standardized all of them so that they could all sort of play together,” Ahtone explains.

Financial Binds of Leasing Tribal Lands

In some cases, tribes lease these state trust lands within their reservations — essentially paying to use what was once their own land.

An estimated 58,000 acres across several states are leased back to Indigenous tribes for agriculture, grazing, and other uses. The Ute Tribe, for instance, leases the highest acreage among tribes. For these tribes, the cost of leasing state trust land is often more feasible than attempting to go down the bureaucratic and legal avenues needed to secure ownership rights.

This financial challenge is compounded by issues of data transparency and accuracy. Many states don’t make lease information publicly available, leaving reporters and researchers with an incomplete picture of the true extent of trust lands within reservations. In some cases, outdated or inconsistent cartographic records show that parcels of land don’t always align with recognized reservation boundaries, creating an information gap and legal complications for tribes hoping to reclaim or manage these lands.

What Lies Beneath: Surface and Subsurface Rights

State trust lands often include subsurface rights, allowing states to retain ownership of underground resources even if or when surface land is transferred back to tribes.

As states aren’t legally required to consult with tribes about subsurface activities, oil, gas, and mineral extraction can occur with little regard for tribal interests or environmental protections. In the case of split ownership, where a tribe might hold surface rights but a state retains subsurface rights, subsurface activities such as fracking or drilling can proceed regardless of tribal consent, posing potential risks to water sources and soil health.

This split ownership situation complicates land management and tribal sovereignty. For example, the investigation found that, in Pavilion, Wyoming, residents were forced to live alongside heavily polluted water supplies due to fracking activities on subsurface lands they had no authority over.

Pathways Forward

Ahtone tells GIJN that continuing to investigate the topic of state trust lands paints a clearer picture of the impact the US federal government has had on Indigenous lands. In the states of Washington and North Dakota, legislative efforts are now underway to facilitate land exchanges that would return state-held lands on reservations in exchange for federal land elsewhere, as part of what’s known as the LandBack movement.

“Every time we do these stories there’s a lot of work to get them off the ground and they take large teams to sort of make happen,” Ahtone says.

“And especially in this last one, I think we highlight in the story that there is an old and racist idea that Indigenous peoples are living off the government or something like that and I think that our reporting continues to show that that isn’t the case. It’s, in fact, the other way around.”

For example, while revenue generated from state trust lands within reservations are often funding public schools, which are attended by Indigenous youth, the curriculum often falls short when it comes to teaching Indigenous history. As a result, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, who live on the Flathead Reservation in Montana, are suing the state over the failure to teach the mandated curriculum.

“Our sources have been quite clear that this is a very particular moral issue in the US when it comes to trust lands inside reservations,” Ahtone says. “But how do you have that conversation with individuals who don’t want to see their taxes go up to fund their children’s K-12 schools for instance, or hospitals, or universities?”

Sharing Data Resources to Fuel More Stories

Grist has been sharing the data it collects with newsrooms before publication, holding training sessions to show reporters how to use the information, and partnering with news organizations.

Ahtone said that data from its most recent investigation was used by Flatwater Free Press, a Nebraska-based independent nonprofit newsroom.

“They had taken the data and did a local version of the story and pushed a little further to figure out the tribe in question in Nebraska, Santee Sioux, who had trust lands on the reservation were also leasing it,” Ahtone explains. “That’s something that we couldn’t see in our story because they didn’t have lease information available. So that reporter pulled down the data, played with it, called up the tribe, and figured out that they were also leasing land… They just pulled it down and did their thing.”