In September 2024, an investigation by the UK-based i-paper revealed that a particular model of a US-made “precision” bomb was used in Israeli strikes on schools and tented camps in Gaza, killing scores of civilians. The site also presented evidence suggesting that a preference for the use of this GBU-39 urban warfare bomb among Israel’s allies had encouraged more bombing by Israel in civilian environments, and, paradoxically, led to potentially more civilian casualties.

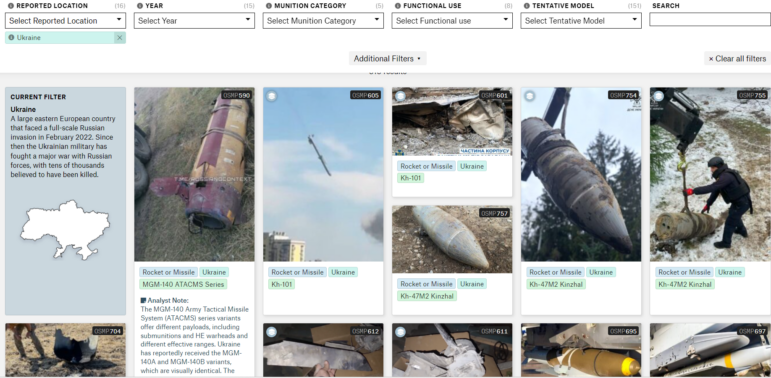

The reporter, Taz Ali, relied on an innovative new database called the Open Source Munitions Portal (OSMP), which identifies and shows remnants of explosive devices in conflict zones, along with linked descriptions and some reports of civilian harm.

There are other excellent and more detailed resources for journalists to research munitions, including the comprehensive CAT-UXO unexploded ordnance database. However, what makes OSMP so useful for investigative reporters is that it helps identify weapons systems the way journalists and, more importantly, victims and media sources typically encounter them: as steel fin blades or blackened wiring or charred cylinders scattered near bomb craters.

OSMP is a project jointly created by the UK-based nonprofit civilian harm watchdog group Airwars and the technical intelligence consultancy Armament Research Services (ARES). In addition to photos from NGOs and direct contributions via an email account, [email protected], many of the OSMP’s images are collected via searches on, particularly, Arabic and Ukrainian-language social media, and then reviewed by munitions experts through several verification rounds. The tool’s early library includes almost 600 images of munition types after their use in current conflict zones, and the project ultimately hopes to feature thousands more, as well as 3-D renderings of the original missiles and bombs so reporters can visualize the origin of discovered parts on the ground.

Independent outlet Danwatch has previously shown that F-35 fighter jets conducting airstrikes in Gaza were using Danish military equipment, but it conceded in its reporting that it was not able to document the aircraft’s participation in a specific attack. However, it was able to do so for the first time in a report on September 1, thanks partly to OSMP evidence, and expert analysis from ARES – showing Denmark’s links to the use of 2,000-pound bombs on the Mawasi “safe zone” in Gaza on July 13.

Danwatch reporter Charlotte Aagaard tells GIJN: “The OSMP presented me with a key piece of evidence for my story on Danish-equipped F-35s being involved in an airstrike that might constitute a war crime. The piece of munition proved that the IDF had used very large munitions which, according to the UN, should not be used in densely populated areas.”

Building a Database of Deadly Pieces of Steel

In an interview with GIJN, Joe Dyke, head of investigations at Airwars and co-creator of OSMP, says the portal was created not only to help reporters use spent munition pieces as evidence for accountability stories, but also to educate journalists in a generally inaccessible technical field.

“The vast majority of journalists don’t have munitions experts as contacts, and so we came up with this idea that, while you still need an expert to 100% verify a munition, we could raise every reporter’s knowledge a little in this area with an accessible portal, and link it to real-world cases,” Dyke recalls. “It’s bringing together our focus on accountability and accessibility, and ARES expertise on identifying spent munitions.”

He adds that it was important to create a real-world, visual database of what munitions look like on the ground, after they’ve been used. “As journalists, we’re always at the other end of the periscope – we’re not dealing with munitions in their complete state,” he points out. “We don’t want [items in the tool] to be hypothetical, so, where possible, we want them to be linked to specific incidents, and especially civilian harm incidents.”

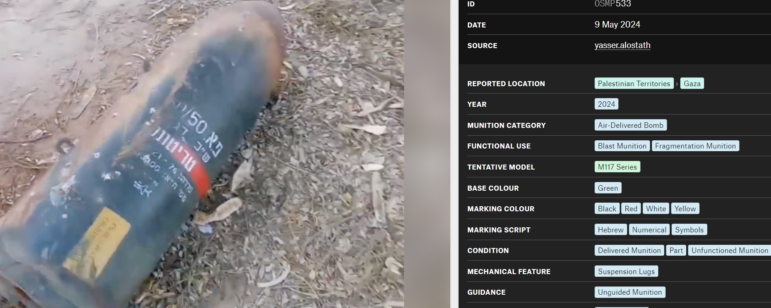

Found in the Palestinian Territories this year, this Korean War-era “demolition bomb” is the kind of high-explosive “dumb” munition that could provoke critical questions about military bombing strategy and potential war crimes. Image: Screenshot, OSMP

Despite years of experience covering conflict as a correspondent for AFP in places like Beirut, Ramallah, and Jerusalem, Dyke realized that he lacked sufficient knowledge to distinguish between, say, spent mortar shells and artillery shells and that there were few accessible resources for reporters.

“If you had a hunch that some remnant on social media may be from, say, a Hellfire missile, you could click on ‘Hellfire’ in OSMP, and see all of our munitions remnants for Hellfire that we have [documented] already,” he explains. “We have 31 images just of GBU-39 remnants, mostly from the last few months in Gaza, and some also from Ukraine.”

He adds: “We are now going to build a 3-D model of this weapon model for the page, so if you hover over the fin, it will pop up images of the fin as it appears in conflict zones.”

Advanced filters include basic visual characteristics that can serve as leads — such as “base color” and “marking script” (say, Cyrillic or Chinese or numeric script) — and primary searches can be filtered for munition type or location.

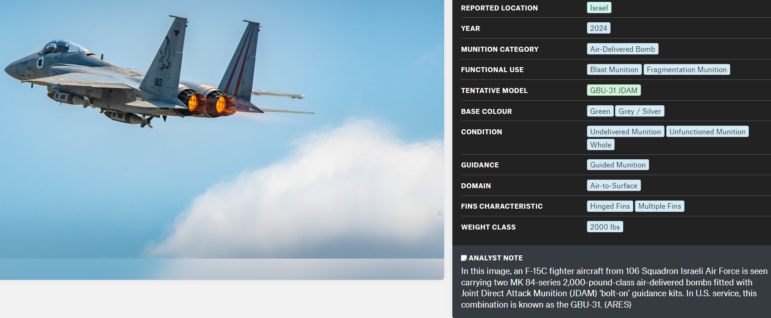

An OSMP image and accompanying description of an Israeli F-15 jet carrying MK84 bombs fitted with JDAM guidance kits. Image: Screenshot, OSMP

Using OSMP and Airwars Together

Airwars has already generated numerous investigative impacts with its two primary functions: a database of 73,000 fully verified civilian non-combatant deaths over the past decade from airstrikes and artillery in eight Middle East conflicts, as well as initial civilian harm investigations on major incidents in which they partner with major media sites.

“Airwars was originally a documentation organization,” Dyke explains. “So if you as a reporter want to know how many civilians were killed by Russian airstrikes in Syria between X date and Y date, we can pull that data for you from our civilian harm database. But, in 2020, we set up an investigations unit in addition, because we found that documentation alone was not leading to all the impacts because journalists are busy with multiple beats, and we often need to also find them the story to get them invested. We kind of take stories to media partners at an early stage and they drive it forward from there.”

One tip Dyke suggests: reporters can generate story ideas by browsing the Citations pages on Airwars. Another suggestion is that reporters can use OSMP and Airwars civilian harm incident reports in conjunction, as Taz Ali did in combining GBU-39 remnant evidence from OSMP with an Airwars case study of an August 10 airstrike on the al-Tabi’een school in Gaza’s al-Daraj neighborhood. In its incident report, Airwars identified 89 individuals by name who were casualties in this airstrike. The i-paper story confirmed a recent ramp-up in the use of the bomb indicated by OSMP data with sources at Janes, a defense intelligence firm.

Danwatch’s Aagaard says the websites and social media accounts of defense departments and weapons manufacturers are also surprisingly helpful in munitions investigations “as both tend to brag about their military achievements or tenders won, or the technical advantages of their products.”

Aagaard concedes there remain several investigative challenges to airstrike accountability stories. “One is to be sure that the open source videos or photos are properly geolocated and can be attributed without a doubt to a particular attack,” she explains. “Another is to know exactly which aircraft, or type of aircraft, has delivered this particular munition. One way is photos or video of munition remnants combined with documentation that this type of munition is generally used, or could be carried by, this particular type of aircraft. Another way is to document that this particular type of aircraft was in the air at the time of the attack.”

Many munitions in the OSMP tool are directly linked to Airwars incident reports on mass civilian casualties that include geolocation data and social media sources, which offer user “unblur” options for graphic content.

Tips for Using OSMP Data

- Find more images via the “Research organization” filter. Reporters can discover additional independent weapons investigations by organizations such as the open source research group Bellingcat via this filter, as well as many more images of missile and bomb parts in situ. For instance, you can find rare images of parts of the secretive RX9 kinetic missile — which does not explode, but rather uses lethal blades — by first using the portal filter, and then clicking into the Bellingcat report.

- Discover telltale features to look for. The portal includes resource pages that show what parts to look for on the ground for each munition type: the distinctive parts most likely to survive detonation. For instance, it explains that tail assemblies and the suspension ‘lugs’ used to attach bombs to aircraft are prime candidates for discovery after aerial bombing. “These pages offer a visual guide to what is an air-delivered bomb or an artillery projectile, and it will also tell you which parts are most likely to survive contact after exploding,” Dyke explains. “So, with mortars, you’re looking for the tail fins, etcetera.”

- Use visual evidence to prompt further investigative questions. For instance, some 2,000-pound MK84 “megabombs” are fitted with Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) kits which allow them to be guided to their target after release. So if the telltale “strakes” from these kits are discovered near a destroyed hospital or school, one question might be: does the presence of JDAM mean the building was deliberately targeted?

- Find linked investigations for accountability leads. The portal includes External Research sidebars, which offer leads on parties culpable in harm via linked investigations — such as this CNN article showing the use of a US-made munition in a civilian area.

- Beware alternate names for munitions. As the portal’s analysts note, reporters should be aware that militaries and weapons manufacturers assign different names to the same bomb or missile. For instance, the US Air Force and some allied militaries use “GBU-39,” while its manufacturer uses “Small Diameter Bomb” or “SDB.”

- Counter misinformation and propaganda claims with analyst notes. Many items in the OSMP include extra details and explanations from ARES experts that can be used to counter erroneous claims and common misconceptions. Referring to an image of a small, heavily riveted nosecone found in Israel in July, Dyke notes how the tool and its date of inclusion in the OSMP database help to establish where it came from and avoid misinterpreting the situation on the ground. “For instance, if you found that on the ground in Israel right now, you’d probably assume it was something fired by Hezbollah,” Dyke says. “I personally would have thought that was the front of some kind of inbound rocket, and you often see people posting these kinds of images as evidence of attacks on neighborhoods. But this was actually from an air defense missile launched by the [Israel Defense Forces].” The attached analyst note states: “This image shows the nosecone from an Israeli Tamir surface-to-air missile. This component is often found as a remnant after the functioning of the missile.”

- Use OSMP in combination with crowdsourced mapping tools. Reporters can cross-reference airstrike incidents in remote places with searches on crowdsourced portals such as Liveuamap (Live Universal Awareness Map), as well as with expert databases such as CAT-UXO.

- Use analyst notations as a fact-checking guide. OSMP’s library can help editors and fact checkers verify initial claims about weapons used, since even official sources on the ground can easily mistake, say, a tank round for an artillery round. However, note that OSMP’s remnant identifications are also not definitive, and are always described as “tentative” identifications by experts; a point reporters should note to audiences for transparency.

- Use OSMP as an orientation and learning tool. Simply browsing images and analysis of spent munitions can prepare journalists for new visual evidence. While he stresses that reporters do not need to be experts in munitions, Dyke says journalists investigating conflict should ideally use tools like OSMP to develop a basic understanding of ordnance categories — like those shown in the visual catalog below.

A visual catalog of different types of munitions. Image: Screenshot, OSMP

Both the OSMP library and the Airwars investigations speak to an important investigative principle that was echoed in a recent GIJN story on dishonest officials in the US elections: to not allow stories to be delayed, or “stuck,” by a perceived need to be comprehensive. Instead, as Dyke says: go with what you’ve got, but also be transparent to audiences about limitations, and build and update after initial publication.

“As our director [Emily Tripp] always points out, what we are not claiming is that X is the definitive set of information about an incident,” Dyke says. “If, months later, someone comes with evidence that, actually, three more civilians were killed in that earlier incident — or some of those we recorded were actually militants — we’ll update our data. Nor do we make legal judgements or call something a war crime: we are not a legal organization. Rather, we document and verify, and our incident reports are jumping off points for other investigators to use.”