In early 2024, the Nairobi-based data studio Odipo Dev partnered with the data journalism collective Africa Data Hub to understand an ongoing epidemic of femicides inside Kenya. For the project, called Silencing Women, the two groups created a historical database that compiled the names and death circumstances of the more than 500 women who had been killed as a result of domestic violence across the country between 2016 and 2023.

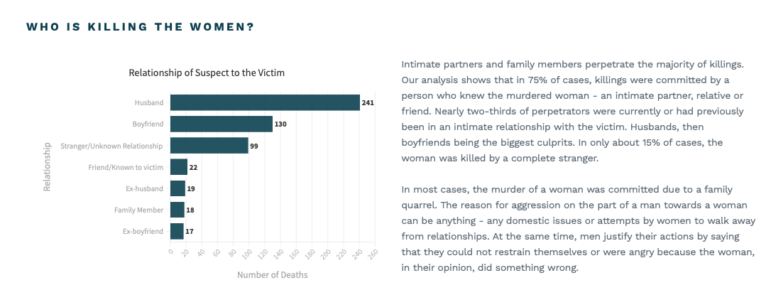

“When we put out the database, we saw our findings demystifying many things people are saying about [those] women,” says Felix Kiprono, head of media at Odipo Dev. The data, he explains, was the first statistical evidence disproving the assumption that the victims were often putting themselves in dangerous situations. “We found that 75% [of the 500 cases] of women are getting killed by a husband or boyfriend.”

The project’s work had an almost immediate impact on the country’s judicial system. Just months after the project was launched, a Kenyan presiding judge cited the Silencing Women database during her sentencing of a man found guilty of the murder of a businesswoman who was killed in her home in 2018.

For Kiprono, this is just one of their many efforts to hold leaders accountable in Kenya. “Data opens up a lot of things,” he says. “It helps you to understand that story more clearly. It provides a reference point. When you put all that together, there’s something that happens. You begin to see the big picture of things.”

The Silencing Women project is by no means a singular phenomenon. Across the continent, data journalism is experiencing numerous successes, rapidly becoming a powerful tool for transparency, accountability, and social impact. But data journalism in Africa still faces numerous obstacles, including a lack of access to reliable information, particularly from repressive governments, a need for more training to increase the knowledge base among the current and next generation of reporters, and a dearth of financial support to grow the field.

The Silencing Women data project was the first to comprehensively study the data on femicide in Africa, and its information has since been used to inform prison sentences for those convicted of killing women. Image: Screenshot, Africa Data Hub

How COVID-19 Changed Data Journalism in Africa

The COVID-19 pandemic was a turning point for many data journalism platforms across Africa. For The Outlier, a South Africa-based site, it marked the start of their data-driven reporting. “We had nothing else to do,” recalls Alastair Otter, co-founder of the project. So, he says they started creating dashboards to track the pandemic’s impact.

These dashboards became a crucial source of information for South Africans, providing weekly newsletters that contextualized the government’s figures, showing trends in hospitalizations, deaths, and vaccinations. They collected and interpreted data to show trends and patterns, as well as monitor government responses and implementations of relief programs.

This information was then made available freely for other news media to use in telling stories. Otter said they had about 40 charts covering the whole of South Africa at a national and provincial level and the team raised around 120,000 rand (US$6,700) in donations that covered the cost of storage. (The Outlier stopped updating the dashboard in 2022, but published a summary of two years of COVID-19 data visualizations in their article Two Years of Coronavirus in South Africa.)

“Data is a very empowering thing,” Otter says. “I’m not saying the data never lies, because data can be twisted, but data done well and responsibly can empower people to move things forward.” (Otter formerly worked for GIJN from 2018 to 2022.)

While the pandemic was the start for The Outlier, other data platforms across Africa were already using their ability to handle large data sets to help others make sense of their new world. In Nigeria, Datapyhte monitored relief funds and the distribution of relief materials across the country; Nukta Africa monitored the impact of the pandemic across sectors and how Tanzanians were responding to their changing reality; and through the Open Cities Lab, Africa Data Hub countered misinformation using data and developed tools to track cases and vaccination rates.

The Africa Women Journalism Project (AWJP), a women-led data journalism platform that reports issues across the continent, investigated COVID-19 public spending in Kenya, Uganda, and Nigeria. The project uncovered mismanagement of funds meant for health services. This data-driven reporting led to public outcry and discussions about how to improve transparency in government spending.

One of AWJP’s reports examined Kenyan counties’ preparedness to handle the virus as casualties climbed and the second wave hit Kenya. The report, published in partnership with The Star, a news website in Kenya, found that county governments were underprepared to deal with a resurgence of COVID-19 patients. The report interrogated data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) to draw projections and reconstruct scenarios at the county level.

Data Journalism as ‘Decision Science’

There remains a big gap between raw data and digestible, actionable information that can shape opinions and inform decisions. In Nigeria, Dataphyte, a data hub founded by Joshua Olufemi, seeks to translate complex data into easily understandable stories, enabling Nigerians to make informed decisions. “Traditional journalism often fails to make complex issues accessible,” Olufemi said, adding that Dataphyte is changing that by using data as a communication tool, rather than as an afterthought.

This approach allows the organization to shape conversations and provide its audience with valuable data that can inform not just civic engagement, but also personal views. This was evident when the team used historical data to provide key insights about the outcome of the 2023 elections in Nigeria. Olufemi said the project was a response to the propaganda and manipulated polls used by politicians to sway people’s opinions ahead of the election.

“We’re not just telling stories; we’re creating evidence that can be used to demand accountability from those in power,” he says. “So decision science for us is a micro-level benefit that goes to our audience in making those livelihood, lifestyle, and living decisions.”

In Tanzania, Nukta Africa has also embraced data-driven storytelling. The platform, led by Nuzulack Dausen, uses data visualizations and infographics to make complex issues, such as public health and education, more accessible to Swahili-speaking communities.

“We wanted to create that society that would make decisions based on data,” Dausen explains. “Sometimes we design icons from scratch to help simplify data visualization in a way that our people will better understand. There are times when the icons available do not depict our realities either. We design our icons to show those realities.”

In other situations, data journalism sites in Africa are creating structures for ongoing accountability.

For example, Africa Data Hub has created a Chrome extension that highlights names linked to corruption scandals whenever they appear in news stories or web searches. Users can click on these names to access the corruption allegations against them, bolstering efforts to promote transparency.

The Outlier has done something similar around the long-running health problem of pit latrines in South Africa. After several high-profile deaths of children in these outdoor toilets, President Cyril Ramaphosa called for the phasing out of pit latrines in schools. The Ministry of Education was given three months to develop a plan, but the government’s response lagged behind its promises. By 2021, a South African court ordered the government to remove all pit toilets and replace them with modern facilities, with biannual progress reports required.

Using government data combined with fieldwork, The Outlier monitors the government’s progress in upgrading sanitation and other school infrastructure. Their findings are also used by Section27, a human rights law firm, as part of the necessary evidence to verify the government’s reports in court.

Challenges for Data Journalism Remain

Despite these successes, data journalism in Africa still faces difficult obstacles. Access to reliable data is among the biggest challenges. “Governments often restrict access to data, making it difficult for journalists to get the information they need,” Olufemi explains. This lack of transparency is a common issue across the continent, where data is either unavailable, difficult to obtain, or lacking local integrity.

There is also the technical skills gap. Many journalists lack the training needed to analyze and interpret complex data sets. “We don’t have enough skilled data journalists,” Dausen says. “Sometimes we have to bring in contractors to help us with data analysis because the skills just aren’t there.”

Catherine Gicheru, director of AWJP, said government restrictions and a lack of technical skills make it difficult for journalists to tell data-driven stories. “Many women journalists simply don’t have the training or data literacy required to dive deep into analysis and make sense of the numbers,” she notes.

To overcome these barriers, AWJP — like many other data journalism platforms across Africa — incorporates training and mentorship as services besides just storytelling and news reporting. AWJP equips women journalists with the skills they need to analyze data, create visualizations, and tell compelling stories through workshops and one-on-one mentorship. In instances where data is difficult to access, AWJP journalists use alternative strategies, such as crowdsourcing data or gathering first-hand accounts from communities.

One example of this is the AWJP’s work on gender-based violence in Nigeria, where journalists faced difficulties accessing official data on reported cases, Gicheru says. Instead, they turned to grassroots efforts, collecting testimonies from women and crowdsourcing data to fill in the gaps left by government records.

“There are always creative ways to gather and use information,” she adds.

There are similar challenges in Francophone African countries, despite the “evolution of civic space,” explains Paul-Joël Kamtchang, publishing director of the new GIJN member Data Cameroon.

“Access to information and the opening up of data remain major challenges,” Kamtchang says. He notes that, as of 2024, eight of the 29 African countries with access to information laws on the books are French-speaking. “However, these laws have not adapted to the challenges of open data,” he notes.

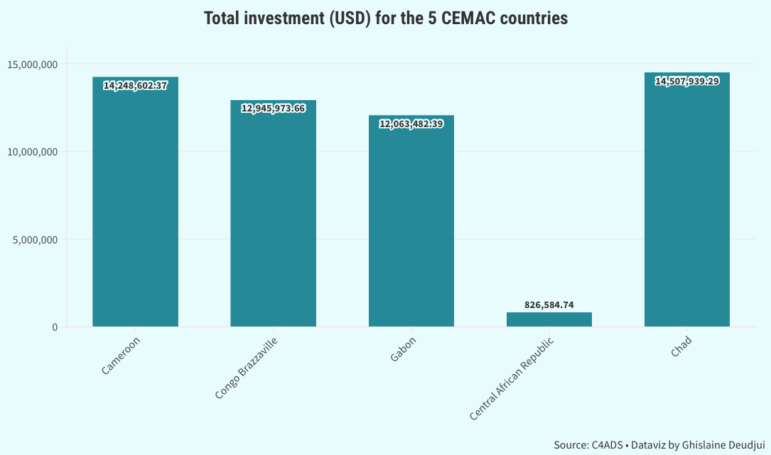

As a result, data journalism is not yet flourishing in Francophone Africa. But Data Cameroon is persevering. They regularly organize scholarships for data journalism academies with the support of partners such as the Washington, DC-based Center for Advanced Defence Studies (C4ADS), a nonprofit focused on illicit global networks.

“We bring in C4ADS data analysts to build capacity at the start of the fellowship, and support our fellows in data collection and analysis,” Kamtchang explains. Stories that developed from these training initiatives include revealing the millions of dollars that Central African businessmen and politicians have invested in Dubai properties and tracing Boko Haram and other non-state armed groups’ involvement in the kidnapping business in the Lake Chad Basin.

Partnering with the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, Data Cameroon used data analysis to reveal the financial stakes of Central African businessmen in properties in Dubai. Image: Screenshot, Data Cameroon

Perhaps the biggest challenge data journalism newsrooms face is funding. While this is a common problem across the journalism industry, it is particularly difficult for data-focused outlets. Dataphyte’s Olufemi warns that there is not enough funding for data-driven stories.

Funding is always a persistent challenge, The Outlier’s Otter said, agreeing. Data journalism is resource-intensive, requiring expensive tools, software, and training. Data journalists rely heavily on grants and external funding to stay afloat.

“It’s not an easy business,” Otter said. “We have to find creative ways to generate revenue, whether through training, events, or collaborations with NGOs.”