Editor’s note: One year after the slaughter of more than 1,200 people in Israel and taking of 254 hostages by Hamas on October 7, 2023—and the commencement of retaliatory strikes and invasions by Israel—the situation remains fraught. Gaza lies in rubble. The Gazan health ministry reports that Israel’s military activities have killed more than 42,000 Palestinians to date, including more than 11,000 children, and have wounded nearly 100,000. The true toll, when uncounted and indirect deaths are factored in, is likely far greater. Some 1.9 million people—about 90 percent of Gaza’s population—are displaced, and relatively few have made it out of the territory. This is the story of one family that did. The events described took place in February 2024. Owing to the uncertain legal status of the family members, who remain in Egypt, the names herein, and that of the author, are pseudonyms.

It’s nearing 9 p.m. by the time we finally agree on Papa John’s. Six pizzas for the 12 of us. Youssef calls in the order. At 16, he’s shed the sweet voice I remember from our calls to Gaza over the years. The total will be $16 at Cairo’s black market exchange rates. The manager calls back a minute later. For such a large amount, they will send someone to take a deposit. Youssef relays the message and someone translates. We laugh at the concept of a down payment on pizza.

My brother-in-law Kamal, Youssef’s father, walks in, and another plastic chair appears as we readjust our circle to accommodate him. My husband, Samer, and I have traveled halfway across the globe from California to help 10 family members—relatives I’m finally meeting in person after 25 years of marriage—settle temporarily in Egypt after escaping the devastation in Gaza.

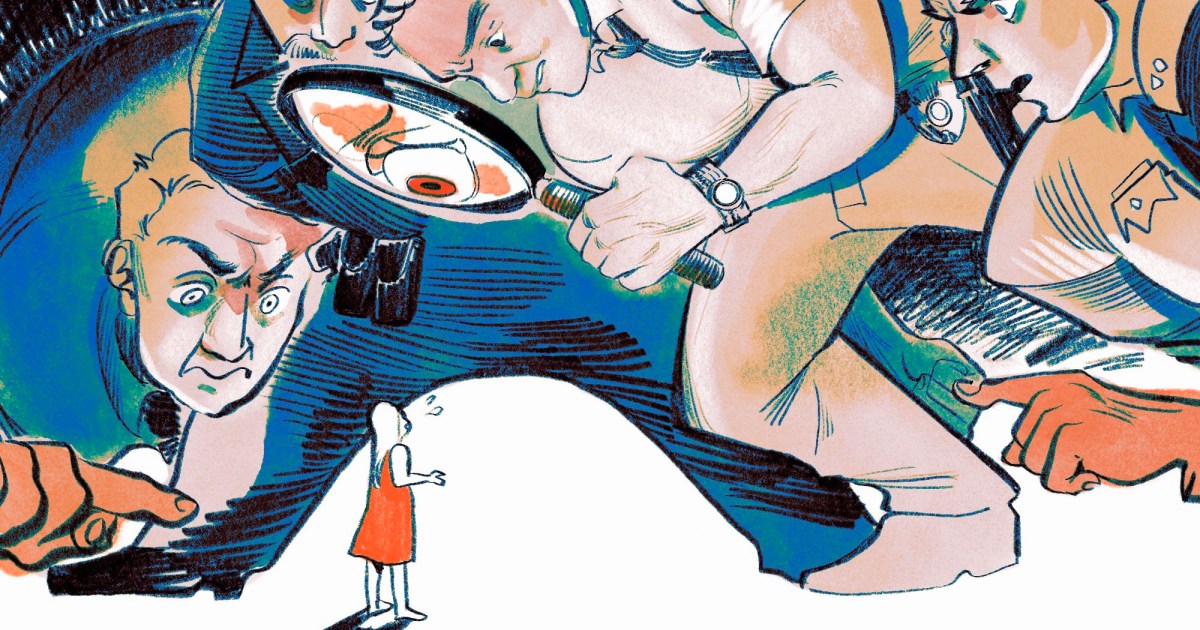

They are here under precarious conditions—some of the more than 115,000 displaced Gazans in Egypt, many of whom managed to wrangle (and overstay) a 45-day tourist visa before Israel shut down the border. But despite their good fortune in escaping the war zone, they have no status outside of it. Neither refugee nor resident, they exist in a legal no-man’s land that prevents any of them from enrolling in school, getting a job, or securing health coverage.

Three family members remain trapped in Rafah—two of my husband’s brothers and one of their daughters. They are everyone’s priority right now. Our seats spill out of the cramped living room into the hall, entranceway, and kitchen of the basic, hastily rented apartment. It doesn’t compare to the three high-rise units in Gaza City the families had to flee, but it is worlds better than their other stops along the refugee railway—sleeping on the floor of their pharmacy supply business, which the Israelis later blew up, and then at the house of a cousin in Rafah shared with 40 others.

Everyone is acutely aware of the hour as we chat about our day, cellphones heavy in our hands. Papa John’s calls back to apologize. It won’t require a deposit after all. The rules always seem to be shifting here. Indeed, why one child was denied exit while six others were not is yet another nonsensical piece of a broader, even more nonsensical puzzle.

My husband and I came to Egypt to do whatever we can to help. And tonight, like so many families in Gaza or Cairo, across Europe and the United States, we are awaiting the Daily List. Thousands of families are trying desperately to get loved ones out of Gaza, though relatively few are successful. The list of people approved for exit by the Egyptian border authority—no more than 250 names a day, a mere trickle—appears on Rafah News, a privately maintained Facebook page that is updated nightly. The family members in Rafah await our call. With no reliable internet, they depend on the diaspora for news of their fate.

All at once, everyone’s phones start pinging with alerts from their social networks, and all heads bow to scour the list. Our Egyptian fixer has assured us that the names will be on it tonight, “100 percent.” This is the sixth day of such assurances, for which my husband and I have paid $21,000. That would buy 7,894 Papa John’s pizzas in Cairo.

Mona, 17, flicks her index finger on her screen, seeking the names of her father, sister, and uncle. She was with them a month ago when her own name appeared on the list. From the comfort of our home in San Francisco, my husband—as the eldest, the de facto patriarch—made the decision on his brother’s behalf: She would be safer risking the journey alone than staying in Gaza. And so Mona was sent by herself across the border, across the Sinai Peninsula.

Tonight, from the group’s downcast eyes, the huddle of their shoulders, no translation is needed. The names are not there.

I had tried to convince my husband that I wasn’t needed on this trip. I don’t speak Arabic and I’d never met his Gazan family. I’d be a woman in Egypt, with little to offer but my patently American optimism. But Samer insisted I was needed for “moral support.”

In Cairo, he assigns me “aunt duty.” My job is to spend time with our nieces, assess them for trauma, and begin to get to know them.

On a Monday, Yasmine, 19, is the first to arrive at our hotel for some one-on-one time. Her mother had said the teen was having trouble sleeping, so I decide yoga might help. I’m no guru, but I know my way around the yoga app on my iPad. One of the routines is set to the music of Queen, but Yasmine has never heard of the band—nor Taylor Swift. Little Mermaid yoga draws a blank, as do the Beatles, so I give up and select a classic rock theme. We find an open studio in the hotel fitness center and lock the door so she can remove her hijab.

I make small talk as I load the class onto my device, remarking how pretty Yasmine is and asking when she’ll get her braces off. She doesn’t know, she says. Her orthodontist is dead, she tells me. Her uncle, too. One day, her cousins, also still in Gaza, were parched, and their father had gone out looking for potable water—snipers shot him in the head. A week later, her grandfather died of a stroke because no hospital had the capacity to take him. I yearn to know more—about others she’s lost and what it’s like for someone so young to endure such brutal circumstances—but I refrain.

The next morning, Yasmine tells me she slept eight hours for the first time in months. I give her my favorite pen and tell her to keep writing in her journal.

Every day, I pluck one or two of my six nieces from their monotony and uncertainty to enjoy a day out with Aunt Allie. Today is Tuesday, and my task is to bring Samira to try a gym where we’ve offered to buy the girls a membership. They desperately need things to do. A month earlier, the last of Gaza’s 12 universities had been destroyed in what the UN has termed a “scholasticide.” Samira has been spending the days of what should be her sophomore year in Cairo, watching endless YouTube videos.

Samira is also 19, and her skittish persona emerges in nearly inaudible whispers. When she does volunteer conversation, her English is excruciatingly halting. Its very simplicity seems to evoke an almost savant-like deeper meaning: “Does Zane ask how we are?”

Zane is my 19-year-old son, her elder cousin by a mere 41 days. The juxtaposition of her life of deprivation with his life of peace and abundance couldn’t be more striking. Samira has lived through four wars and the countless daily indignities Americans rarely hear about—like the Israeli blockades that result in shortages of basics such as clothing fabrics, pens, spices, and toothbrushes; the youth unemployment rate of up to 75 percent; and the throttled electricity, available only about 10 hours a day even prior to the hostilities.

“Does he know us?” Samira’s tone is meek, as though she’s talking to herself, but her persistence signals a certain determination: “Does he know my name?”

I realize she is only inquiring about her cousin, cocooned away at a small liberal arts college in New England, but something in her simple poetry evokes something broader: Despite Gaza’s moment as a global cause célèbre—the hastily produced kaffiyehs, protest encampments, and solidarity marches—much of the world exhibits little interest in learning what a typical childhood in Gaza is like. As Samira might put it, “Do they know about us?”

It was 2 a.m. in Rafah and Israeli bombs were falling. Tamir wanted his big brother on the line. I gripped Samer’s hand as we listened to sounds of destruction over his cellphone speaker.

My husband had warned me about the Islamic dress codes, but the lightest long pants I own—a pair of cargo tights—aren’t nearly light enough for the gym’s 80-degree heat. They do, however, have side pockets perfect for carrying the stacks of $100 bills we brought to Cairo, where everything revolves around wads of cash. In a dark parking lot, we swapped our Benjamins for a backpack full of Egyptian pounds, which we emptied at one point onto the apartment’s coffee table, bringing to mind Scrooge McDuck or a B-movie drug deal.

I dispatch some of the pounds on a personal training session for Samira and a short-sleeve shirt to replace her heavy sweatshirt. She’s never been on a treadmill. I recall her saying she missed Gaza’s beaches, so I ask the trainer to put on a beach-themed background video. The beaches aren’t the only thing she is missing. Her twin sister, Amal, is one of the three relatives who remains in Gaza. The sisters have been separated for over three months. How or why or who decides, we have no idea.

Later, after a shower, changing back into our street clothes, Samira realizes she’s forgotten her brush. She looks at me in utter confusion and asks what to do. I fish a ponytail holder out of my bag and hand it to her. In the few days I’ve known her, I’ve found her often in moments like this, lost and frozen, utterly overwhelmed—perplexed by her circumstances and, I suspect, all she has been through. She can’t grasp my suggestion of a quick finger brush. She asks if I will buy her a new one. I leave and return minutes later with a two-pack. “One is for Amal,” I tell her.

“I feel happy just hearing her name,” Samira says.

As we exit the gym, the shops in the adjacent mall are putting out special goods and decorations for Ramadan. I consider an advent-like calendar with flavored dates behind perforated cardboard doors. Twenty-four days until Ramadan. I wonder if Samira is counting them down.

A member of Israel’s war cabinet had promised that Rafah would be invaded if the remaining hostages weren’t freed by the start of the Muslim holy month. (The invasion ultimately would commence May 6, some two and a half months later.) Back in California, we’d had a preview of what that might look like. Tamir, one of my husband’s brothers, had called just as we were about to set out on a pretrip shopping expedition. It was 2 a.m. in Rafah and Israeli bombs were falling. Tamir wanted his big brother on the line. I gripped Samer’s hand as we listened to sounds of destruction coming over the cellphone speaker.

The dialogue was sparse: “Did you hear that?”

“Something has fallen in the yard in front of the house.”

“The windows have all shattered.”

At some point, Tamir said his throat was dry from the dust—and fear. “Can you stay on the line with Amal while I go look for a drink?” he said.

I was grateful the conversation was in Arabic, as I wouldn’t have known quite what to say to his teenage daughter. Samer kept asking her questions that felt absurd, given the situation: “How are you?” “Are you still there?” Amal replied she was “fine,” as though exchanging pleasantries with an acquaintance at the supermarket.

We had an oversized suitcase back at home waiting to be loaded with shoes, winter coats, and T-shirts with random slogans, so we took the call on the road. By the time we arrived at the store, the apocalyptic soundtrack had receded, and Tamir traded the comfort of our voices for an attempt at sleep.

Back in Cairo, after our workout, Samira and I join the other nieces for lunch. I suggest McDonald’s, which doesn’t exist in Gaza—a golden arches meal is practically a bucket-list item for kids there. I realize I’m being provocative. Given the US military support for Israel, some Egyptians have boycotted American franchises, and many of the displaced Gazans have joined them.

Just as US businesses showed support for Ukraine in the wake of Russia’s onslaught, so businesses in Cairo have incorporated the Gazan cause into their marketing. Palestinian flags adorn takeout coffee cups and storefronts. Our Papa John’s pizza boxes have stickers reading, “Fresh,” atop a silhouette of historic Palestine, which encompasses most of Israel in addition to Gaza and the West Bank.

The sticker makes me uneasy, as I grew up supporting Israel’s right to exist and defend itself. But that support obviously does not stretch to the eradication of my lunch companions—or Lebanese civilians or anyone else just trying to live their lives. One would be hard pressed to create a sticker that accurately depicts today’s Palestinian territory. The Gaza Strip is a speck on the sea. The West Bank, a 90-minute drive to the northeast, resembles a piece of Swiss cheese—a pocket of enclaves picked apart by an expanding cycle of illegal Israeli settlements and the buffer zones set up to protect them. Between the two lies the inaccessible state of Israel.

We settle on an outdoor restaurant where I entertain the girls by ordering in Arabic. A commercial airliner flies overhead, and Laila nudges Noura to look up, as though she’s just spotted a double rainbow. Laila is 17, Noura, 12. In Gaza, they only ever saw military jets—even during times of relative peace.

The girls ask me endless questions: Do I like hummus? Why don’t I eat meat? Have I ever seen snow? Where will they go after Egypt? I stick to the short term, reminding them that our priority now is on getting everyone safely out of Gaza: “After that, when your fathers get here, we will talk as a family.”

The reality is that everything they know has been shattered—literally, fragments of cinder and glass strewn across the trappings of their childhoods. The circumstances may call for optimism, but they want to know what is next. For now, I can only offer the girls our financial support, do desperate Google searches for “countries accepting Gazan refugees” (answer: none), and insist that they order dessert.

Still, the afternoon at the mall boosts our spirits, and we bring a sense of optimism back to our nightly chair circle—hope amid despair. The fixer has upped his “100 percent assurance” with a confident promise of “a million dollars” if the names don’t appear tonight. We’ve extended our stay until the weekend, but I feel in my bones that this is the day.

It’s Wednesday now, and I’m taking Laila and Noura on an outing to distract them from the reality of yet another day estranged from their father. Neither the names nor the million dollars made an appearance last night.

The girls come to meet me at our hotel and can’t stop craning their heads around. They’ve never been in a hotel. I watch as they take selfies, the charcoal black of their French braids a perfect contrast to the ornate lobby’s white marble. Laila, who is perpetually smiling, wears a sweatshirt with “So Happy to Be Here” written across the chest.

Between Israeli “security” measures and extremist Islamic censorship, the nieces also grew up without movie theaters. It’s as though the Israel Defense Forces and Hamas have colluded to deprive Gazan kids of the simplest pleasures. The girls and I have pinky sworn that I will get to have the honor of taking them to their first silver screen experience, but a secondary promise has us agreeing to wait for Amal. So today, we’re headed back to the shopping mall.

Like actors playing people in normal circumstances, we chat about fashion. “We can’t wear short skirts because we are Muslim,” says big sister Laila, who tends to speak for the two of them. I ask them why they don’t wear headscarves. The girls wrinkle their noses in distaste. “In the public schools, we’re required to wear hijab, so we begged our parents to send us to private school.”

Noura bobs her head in agreement. Laila gestures to her own jeans and sweatshirt, modest yet fashionable. She could pass for one of my son’s California friends. “In Gaza, people sometimes look at us funny because of how we dress.”

Western dress can be considered quite rebellious in Gaza. “Here, in Egypt, no one cares!” Laila’s smile could melt mountains of the snow she’s never seen. Noura nods emphatically, echoing the sentiment.

At H&M, Laila beelines toward a tight, short dress. Her eyes go wide as she asks whether she can try it on, and we giggle as she admires herself in the sanctity of the dressing room. Noura dons a more conservative sweater. Absent of her baggy sweatshirt, I notice her sagging jeans and protruding ribs. “We all lost weight in Rafah,” Laila explains casually. “There wasn’t enough to eat.”

In the third or fourth store, maybe the fifth, Laila spots a navy-striped sweater: “I had one just like this at home.”

She’d shown me “home” the day before. A neighbor’s video walkthrough revealed exterior walls with cavernous openings, carpets of shattered glass, and belongings heaped in piles amid the wreckage. Next to Laila’s neatly made-up bed stood a blown-open wardrobe, a stuffed Sesame Street Ernie hanging from its door handle. I watched her watch the footage of a bedroom she would never see again. Miraculously, she was still smiling, dimples as deep as the craters in the walls of her room.

I offer to buy her the navy-striped sweater, but she politely declines. She does accept a multipack of earrings. We pick out an extra pack for Amal, hopeful that her name will make tonight’s list.

It does not.

Back at the hotel, the turndown service has left my husband and me a three-tiered silver cake stand overflowing with bite-sized pieces of baklava, petits fours, and macarons. We call the airline and push our departure back another two days, even though we’ve mostly resigned ourselves to leaving without getting Tamir, Nabil, and Amal to safety. Hope is an aberration in the deserts of Gaza.

I try to imagine what Amal is doing. I know she’s in a house with perhaps 30 others, windows long shattered, but at least they have four walls and a roof. The food is ample, but canned. Water is sparse. I also know the border is tantalizingly visible from that roof—so close that an Egyptian SIM card allows her to message her sisters in Cairo.

It’s Thursday and I’m killing time with Yasmine and her mother at the apartment.

As the 9 o’clock hour nears, the rest of the family joins us. We’re nibbling nervously at a mound of dolmas when I see Mona’s head bend toward her phone. A former neighbor has sent over a copy of the Daily List via WhatsApp. All three names are on it!

There is no dancing, whooping, or jubilatory squealing. It’s as though we have opened a small crack for our pent-up tension to escape slowly, like air from an improperly knotted balloon. Quiet, broad smiles emerge on our faces. Relief proves stronger than jubilation.

The trio’s journey from Gaza to Cairo is arduous but uneventful. We follow their progress via incoming texts.

In line on Gaza side.

Through Rafah gate.

In departure hall.

In line for bus.

On bus to Egyptian side.

In line at arrival hall.

Crossed to Egyptian side.

In line for bus.

Crossing Sinai.

Their 200-mile trip takes nearly as long as our 7,500-mile flight from San Francisco. My husband and I have decided to give each family subunit the freedom to reunite in private. We spend the day making arrangements for our return and setting up a GoFundMe page to help defray our fixer costs and cover the families’ living expenses for the next six months to a year.

Some friends of ours who are GoFundMe veterans have advised us to put lots of specifics in the postings, but there are few to be had: Everything from schools to housing, even the question of whether our relatives can be technically classified as refugees, is up in the air, and it all could take months or years to sort out—if it’s even sortable. No nation has yet embraced the fleeing Gazans. When I inquire with a refugee agency about a US family reunification visa for my brothers-in-law (not even including their families), I am informed me that the average wait time is 15 to 20 years.

On Saturday morning, Tamir, Nabil, and Amal, our new arrivals, come to visit at our hotel. I stand on tiptoes to hug Nabil, who is 6-foot-7. I bend down for Amal. Born with severe scoliosis, she’s barely 5 feet tall, and my arms overlap around her tiny frame. I’m three times her 19 years and yet, given what she has been through, I feel humbled in her presence. My words feel clichéd: “It’s so, so good to see you! I’m so sorry this took so long.”

“I’m the one with the black-sheep bad luck in the family,” she says. Her nose crinkles when she laughs, and her eyes sparkle with mischief.

We escort the trio down the hotel’s imperial staircase for an expansive breakfast buffet. My brothers-in-law pile their plates high with a potpourri of cheeses—cheese and eggs, they say, are the foods they missed the most. Servers circle the room with drink refills and fresh bread, and the contrast of the scene with their existence in Rafah just 24 hours before is as ludicrous as it sounds.

Standing at an omelet station, Tamir apologizes for his hastily purchased sweatshirt, explaining that he hadn’t changed his clothes in 90 days. Six feet away, Amal is practically frozen by all the food choices. I wonder aloud what it must have been like for her to wear the same thing for so long. Tamir dismisses me with a smirk. Amal, he says, organized an exchange with other teens in the house—they traded “new” clothes constantly.

Today will be her day for pampering. I clumsily offer a variety of options, punctuating each with, “but I understand if it might feel like too much for you.”

“I’m up for everything!” she assures me, downing her third glass of juice.

I suggest another shopping trip—a practical choice, as her suitcase of cherished possessions was lost in the chaos of war. “I’ve decided I’m going to reinvent myself,” Amal declares, now onto a fourth juice. Her optimism is surreal, almost unsettling. I’d half-expected to meet a girl traumatized, hysterical, dirty—lacking hope. Instead, she smells of soap. I’m infected by her radiance, humbled by her resilience. She can’t wait to return to her college studies, she tells me, and she dreams of being an embryologist.

At the mall, we meet up with Samira, her twin. I’ve brought along so much Egyptian cash today that I can barely zip my fanny pack. But Amal is again overwhelmed by possibilities. After multiple loops around the mall, Samira points out that her sister’s hands are cracked and dry from her months in Rafah. Minutes later, we are testing body lotions and scents.

Amal’s thirst resurfaces and she asks me if we can grab a coffee. I hesitate to suggest Starbucks—which is just around the corner, but she spots the sign and shushes Samira’s boycott-busting hesitation with a “Don’t be ridiculous!” She grabs her twin by the hand, leads her through the door, and orders each a caramel macchiato.

The night before my husband and I head home, I finally introduce all six nieces to the joy of cinema. I go full throttle, buying each a bucket of popcorn, a box of candy, and a slushie. The girls are captivated by Madame Web, oblivious to the nearly deserted theater and the film’s 11 percent critics rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Watching their rapt faces, I think about how complex their lives have been, and how surprising their multidimensionality. The way they crave opportunity, not pity. How I came here intent on rescuing them, and instead, I fell in love.

It’s dusk as we leave the theater, the setting sun a gradient of purples, oranges, and pinks—like the colors of Amal’s ruined bedroom. We snap more pictures as she holds aloft the shopping bags with the costumes of her reinvention.

She pulls me close, conspiratorially, her tongue dyed bright blue from the slushie. “This wasn’t how I had hoped it would happen,” she confesses. “But I told you I would get out of Gaza!”