At least a few times a week, when no elections are underway, the Maricopa County recorder’s office hosts tours of the Tabulation and Election Center, or MCTEC, a gray, one-story concrete fortress on the edge of downtown Phoenix where as many as 2.4 million ballots will be sorted and counted this fall. Ever since the 2020 election, when President Joe Biden’s narrow victory in the county helped Democrats flip the state, the site has been the subject of suspicion, threats, and conspiracies.

In response to the chaotic scenes of 2020, when Alex Jones showed up with a megaphone and declared that it was “1776,” the county installed a tall security fence with an intercom system around the entrance. People in four states have been arrested for threatening the recorder, Stephen Richer, whose office is responsible for maintaining voter rolls and mailing out ballots. In March, the vice chair of the county GOP joked about lynching him; in July, she led the state party’s delegation to the Republican National Convention. Richer, a 39-year-old Republican lawyer with thinning red hair, has, in turn, tried to demystify his team’s processes with aggressive transparency.

On a 105-degree Tuesday in June, I joined a small group from a local chamber of commerce for a peek under the hood. Some participants had questions about their own experiences: Why had a relative’s ballot not been counted? What really happened when Sharpie ink bled through a ballot? As we wound through corridors, past rows of printers and stacks of empty USPS bins, Sarah Frechette, deputy registrar outreach coordinator in the recorder’s office, pointed out one safeguard after another. You need a key card to pass through any door, and each card only grants access to certain areas. No one from the recorder’s office can enter the tabulation room—a different agency counts the votes. Just three people have access to the server, which is encased in a small glass room within the tabulation room. No one can enter that room unless another person is present. If ballots are kept overnight, they are stored in secure rooms behind floor-to-ceiling chain-link cages. The only thing missing is a moat.

When we arrived at a beige room with rows of tables where trained workers attempt to verify signatures on mail-in ballots flagged for review, Frechette drew our attention to the ceiling. “Camera…camera…camera…camera,” she said, pointing up. They are everywhere, and they are always on. You can go online and watch the livestreams yourself.

MCTEC is a citadel of lawfulness, where Democrats and Republicans check each other’s work and protect the democratic process in America’s fourth-largest county. Richer refers to the tabulation room as “the holiest of holy rooms.” But outside the metal gates, it’s a different story.

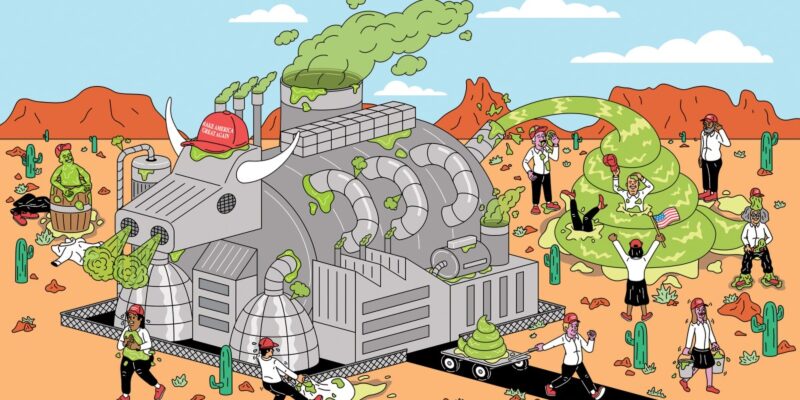

To much of Richer’s party, MCTEC is a crime scene. Almost four years after Joe Biden’s victory, the myth of stolen elections shapes races up and down the ballot and across the state. It has consumed the energy of the legislature and thrown a wrench into the gears of governance through an endless parade of lawsuits and investigations. America’s most volatile swing state is trapped in a time loop: Arizona is where the 2018 election was suspect, the 2020 election never ended, and the 2022 election is literally still being contested.

This obsession with fraud and betrayal has cost Arizona Republicans dearly. What was once a locus of conservative power has shifted slowly but tangibly toward the Democratic column. Republicans have lost a succession of statewide races, alienated independents, and driven officials from their ranks—and sometimes their homes—with threats of violence and retribution. Those defeats have not muted the power of the stolen election narrative; they have reinforced it. In a paranoid party, the biggest winners are the losers. With every setback the Big Lie grows more righteous, more lucrative, and more vital.

The process has at times veered into the comic, but the results are deadly serious. Arizona shows what happens when a conspiracy takes over a party, and election denial becomes not just a tactic but its animating purpose. Processes, such as vote-by-mail, that have for decades made Arizona one of the easiest places in America to vote are now on the chopping block. Officials and low-level workers who have served the public for years are fighting for their jobs—or giving up on them. The very idea that voters should decide elections is viewed with suspicion in some corners of the legislature.

This fall, with Arizona once again poised to play a major role in the presidential election and the fight to control both houses of Congress, and the state legislature up for grabs, election deniers are everywhere. Republicans are no more prepared to accept a Democratic victory now than they were four years ago. And with President Donald Trump leading or within striking distance in most recent polls of the state, the figures who have spent the last four years undercutting the basic workings of democracy might finally reap their rewards.

To see what the recorder’s office is up against, I didn’t have to go far. That same morning, a few blocks north of MCTEC, a small crowd spilled out the doors of a cramped hearing room in the bowels of the Maricopa County Superior Court for the final three arraignments in State of Arizona v. Kelli Ward, et al. The case—in which 11 Arizona Republicans and seven other Trump allies were charged with conspiring to submit false Electoral College certificates in an attempt to overturn the 2020 election—is both a commentary and a meta-commentary on the whole state of affairs.

Kris Mayes, the Democratic attorney general who brought the case, won her election in 2022 by 280 votes; Abe Hamadeh, her Republican opponent, was still contesting the result. Hamadeh had recently filed a fourth appeal, arguing that Mayes should be removed from office and a do-over should be held. He’d been challenging the result for so long that he was now also running for Congress; Anthony Kern, an indicted fake elector since elected to the state Senate, was running against him.

The fake electors were symbols of the state party’s evolution. Prior to 2016, Arizona’s official Republican organizations seesawed between hardcore activists and more mainstream leaders. The Maricopa GOP censured the late Sen. John McCain, champion of the latter faction, three times for purported liberal heresies. In turn, McCain’s allies periodically purged the state and local party of gadflies to restore a veneer of normality. The Trump years, and McCain’s death, effectively settled the debate; even as the electorate in Maricopa County moved to the center, the Republican Party went full MAGA.

Bill Gates, a Republican Maricopa County supervisor who is stepping down at the end of his term after years of threats and abuse, told me that the first signs of an unraveling came in 2018, when Democrats narrowly won three statewide races, including a bid for US Senate. Gates, a 53-year-old lawyer with short graying-brown hair who had previously helmed the state party’s “election integrity” efforts, recalled how Republicans had expressed shock and suspicion at the results, which weren’t called until nearly a week after the election.

Conservatives focused their ire on Richer’s Democratic predecessor, Adrian Fontes, who at the time was responsible for both in-person and mail-in voting. Fontes had run for office on a promise to expand voting access, but presided over a chaotic primary and general election plagued by hourslong waits at some polling stations. The Republican-controlled Board of Supervisors then reached a deal with Fontes in which the board took back control of in-person voting.

“Some of the vitriol in 2019 when I was the chair and I was negotiating that new relationship, I saw it—it was palpable,” Gates said. “Did I see what ended up coming? No, but these pressures were here. They were under the surface and had broken through.”

Afterward, the state GOP enlisted Richer, a Federalist Society lawyer, to conduct an audit of the 2018 election. The 228-page report he produced is striking, both for what it does and doesn’t say. Richer concluded that it was “plausible” Fontes had acted with partisan interest by opening multiple “emergency voting” centers the weekend before Election Day and by continuing to attempt to “cure” mail-in ballots days after polls closed.

Richer’s report also contained traces of past and future conspiracies. His requests for correspondence between Fontes’ office and George Soros, he noted, went unfulfilled. But he also determined Fontes had done nothing illegal, and his report’s allegations of inappropriate behavior were fairly benign and, by Richer’s admission, unsubstantiated. This was a conventional political document, with a conventional political solution. A few months later, Richer declared his candidacy against Fontes. His slogan: “Make the Recorder’s Office Boring Again.”

Behind the scenes, though, the state party was in the midst of a transformation. In 2018, the millennial political activist Charlie Kirk relocated to Arizona from Illinois and began building out a power base around his nonprofit, Turning Point USA, and his PAC, Turning Point Action. Kirk’s Christian nationalist agenda is centered on the Dream City Church in Phoenix, which claimed during the pandemic to have developed a proprietary air-purification system that kills “99.9 percent of Covid within 10 minutes.” (It does not.) He hosts a “Freedom Night in America” rally there once a month; Trump has twice campaigned at Dream City.

These MAGA Republicans blamed their setbacks not on Trump, of course, but on electoral malfeasance and the fecklessness of the McCain wing of the party. At the state GOP’s annual meeting in 2019, a handful of Kirk allies, including Turning Point Action’s chief operating officer, Tyler Bowyer, and Turning Point USA’s former spokesperson, Jake Hoffman, helped elect Kelli Ward—a right-wing doctor who had once proposed holding a state Senate hearing on chemtrails and waged an ugly primary challenge against McCain—as party chair. (The Arizona Republic reported that Bowyer was working on his own time, not Turning Point’s.) In a harbinger of things to come, the Republic reported, delegates insisted on choosing their new leader via voice vote. They didn’t trust the machines.

“In a paranoid party, the biggest winners are the losers. With every setback the Big Lie grows more righteous, more lucrative, and more vital.”

Trump lost Arizona the next year, at a time when many Arizonans were primed to reject such a loss, and reacted accordingly. Although Richer defeated Fontes, his fellow Republicans almost immediately alleged that something sinister was going down at MCTEC—and soon Richer himself would become the subject of conspiracies. A lawsuit filed by Trump lawyers Sidney Powell and Alex Kolodin, on behalf of Bowyer, Hoffman, Ward, and eight other Arizonans who would have served as electors had Trump won, included an affidavit alleging that former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez had helped develop the technology used in Arizona voting machines; a claim that Biden’s lead could have been manufactured “with blank ballots filled out by election workers, Dominion or other third parties”; and a reference to a “former US Military Intelligence” expert who was identified only as “Spider.” Ward pressured the Board of Supervisors to stop the certification. When that failed, according to Mayes’ indictment, the 11 Republicans gathered around a conference table at state party headquarters on December 14 to sign their own set of papers declaring that they were Arizona’s rightful electors.

In their arraignment six months later, Trump lawyers Boris Epshteyn and Jenna Ellis, and fake elector Steve Lamon, pleaded not guilty. (Prosecutors later dropped the charges against Ellis, in exchange for her cooperation in the case.) But Trump diehards still view the underlying event with pride. A video of the signing that the state party posted on X is still up. So is a group photo Ward posted, with the message: “Oh yes we did!” This past spring, four days after the indictments dropped, Hoffman, now a state senator, was elected to the Republican National Committee.

The Arizona efforts to “stop the steal” were merely the prelude to an even stranger quest to expose how the election was supposedly stolen. It is hard to summarize what happened next without starting to feel a little insane yourself. In the months that followed, Republican legislators pursued theories that ballots were shredded, that they were imported from South Korea, that drop boxes were illegally stuffed with ballots, that the tabulators were hacked, and that evidence of voter fraud had been incinerated at a farm where 166,000 chickens died in a fire. (The chicken fire did happen, but no ballots were harmed.) The entire party had become Gene Hackman at the end of The Conversation—delirious, destroyed, surrounded by the shattered floorboards of its paranoia.

In Chandler, Arizona, a QAnon-promoting realtor named Liz Harris tried proving the existence of massive fraud by linking mail-in ballots to vacant lots. But some of her claims could be debunked using Google Maps. Harris was elected to the Statehouse and subsequently expelled for inviting a witness to testify who accused various elected officials of committing crimes on behalf of the Mormon Church and the Sinaloa cartel. In April, she joined Hoffman on the RNC.

The search for clues culminated in 2021, in a monthslong “audit” commissioned by Republican members of the Arizona Senate, paid for by e-commerce kingpin Patrick Byrne, and carried out under the direction of an IT firm called the Cyber Ninjas at a former basketball arena in central Phoenix nicknamed the Madhouse. The Ninja volunteers, one of whom—fake elector Kern—had been on the US Capitol grounds on January 6, were inspired by an inventor named Jovan Pulitzer (not his given name), who claimed to have developed a proprietary system that could detect ballot tampering. They inspected the ballots for evidence of bamboo fibers (to prove they had actually come from China) and shined UV light under them to search for watermarks. (Some QAnon followers believed Trump had secretly marked legitimate ballots.) Pulitzer had previously led a search for the Ark of the Covenant. Evidence of fraud proved similarly elusive.

There was plenty of drama on Election Day, as might be expected in a county the size of Maricopa. Take the Sharpies. Voters who showed up at some polling locations were told to fill out their ballots with markers because the ink dries faster. In some cases, the markers bled through to the other side of the ballot, causing panic among voters. Sharpies formed the basis for one of Trump’s post-election lawsuits, but the case was thrown out because there was no evidence the issue prevented votes from being counted. When a voter brought up the subject on the MCTEC tour, a staffer explained why—the ballot’s offset design was crafted specifically to stop bleed-throughs from affecting the tabulation.

But the spectacle was partly the point. During the audit, the Cyber Ninjas’ CEO partnered with a documentary filmmaker (who’d previously argued that aliens had done 9/11) to produce The Deep Rig, a movie that purported to explain how the CIA influenced the 2020 results. The film premiered in 2021 at Dream City—where the state GOP voted to give Ward another term at its annual meeting that year. (The chair election, which this time used paper ballots, mirrored the party’s crackup; one losing candidate alleged that the election was rigged and demanded an audit, which Ward rejected on the grounds that “you certainly don’t allow a challenger who lost an election to demand something that they don’t have the right to.”) The Cyber Ninja audit was a joke, but a useful one. Politicians and activists learned that there were few consequences to indulging the lie. Quite the opposite—refusing to do so might cost you your job, while egging it on could get you a much better one.

No one understood this lesson better than Kari Lake, a former TV news anchor who resigned after questioning the decision to call Arizona for Biden. As the state party attempted to regroup from its recent setbacks, Lake kept election denial front and center during her run for governor in 2022. She won Trump’s endorsement after promising at a Turning Point event to revisit the stolen election as governor, then hosted a rodeo with MyPillow’s Mike Lindell. Lake was the sort of candidate the Turning Point crowd had been waiting for: a proto-Trump for a shadow party. She spoke at Dream City, rallied with Kirk and Bowyer, and stumped with the organization’s enterprise director (also a state representative). Lake led a slate of like-minded conservatives who vowed to use their powers to take back what was stolen from them. She filed her first challenge to the vote process before ballots were even mailed out.

A few weeks after the 2022 election, Lake had a dream. As she later recounted in her memoir, Unafraid: Just Getting Started, she found herself drugged, blindfolded, and bound with duct tape in the back of a pickup truck being driven by two men. One, with “a batch of ginger stubble, a color match for his thinning hair,” was named Stephen. The other—“short, with greasy black hair, and a face that seemed incapable of bearing any expression other than smugness”—was called Bill. They had taken her to the desert to kill her but were too incompetent for the job. After Stephen fumbled with his Glock, Bill grabbed the weapon and fired wildly in her direction. When she awoke, Lake wrote, her phone was ringing. It was her attorney, bearing news about her lawsuit challenging the election results.

If the villains of 2020 were shadowy foreign powers, Republicans had clearer targets when Lake lost two years later. They blamed Richer and Gates, whose Board of Supervisors was responsible for Election Day administration and tabulation, as well as certifying the results. The losing US Senate candidate, Blake Masters, conceded while nonetheless demanding that Gates resign. But the rest of the slate began a series of long-shot legal challenges premised on the corruption and incompetence of MCTEC. Touring Arizona in the ensuing months, Lake beamed photos of Gates and Richer onto big screens and falsely accused them of “intentionally” causing delays at voting sites and of “pumping 300,000 invalid ballots” into the final tally.

Lake wasn’t merely complaining. She actively attempted to reverse the outcome via lawsuits that aimed to install her in her rightful place in the governor’s mansion. To represent her, she hired a self-described “adventure travel guide” and lawyer named Bryan Blehm, who had distinguished himself previously as counsel for the Cyber Ninjas audit. Blehm is often described as a “Scottsdale divorce attorney,” which is true but incomplete; he is also an expert on motorcycle law. He was not an experienced election lawyer, and by his own admission—in a letter defending himself against an investigation by the state bar—lacked the resources for the task.

Blehm’s case was not strong, in other words. A judge suspended his law license for two months for making a false statement in a state Supreme Court filing and ordered him to take continuing legal education. Lake’s attorneys in the voting-machines action were docked $122,000 for filing a case without merit. Alex Kolodin, the Arizona lawyer who worked with Sidney Powell on the election challenge that cited “Spider,” was ordered by a court to take five different remedial ethics classes. (The cases were a boon for Kolodin, who is now a state representative and a member of the Republican National Convention’s platform committee; he recently posted a photo of himself doing his coursework at a Dream City Trump rally.)

But Lake had strength in numbers. Mark Finchem, an Oath Keeper and former state representative who lost his 2022 race for secretary of state by 120,000 votes, filed his own lawsuit to contest the results and demand a new election. Hamadeh filed a series of similar challenges on his own behalf, which “the crazies love because they see me fighting,” he privately told a fellow Republican. Conceding a lost race went from the norm to the exception, and lawsuits were filed as a matter of course. The recorder’s office has been dragged to court 43 times since 2020. Eventually, citing psychological harm, physical threats, and damaged career prospects, Richer fought back with a defamation lawsuit against Lake.

Republican elected officials have tried to make it easier to flood the political and legal systems with baseless claims. Fake elector Kern introduced legislation that would protect attorneys who filed election challenges, however frivolous. Kolodin, the oft-sanctioned election lawyer, supported a bill that would strip the bar of the power to sanction lawyers altogether. In May, GOP members of the Arizona House called for impeachment of Mayes, the attorney general, in part because of her efforts to prosecute election-denying officials in rural Cochise County, which had failed to certify the 2022 election before the deadline.

Arizona’s elections themselves seem increasingly superfluous. One state representative backed a bill to give the legislature, not voters, power to award the state’s electoral votes. Another pushed a law that would preemptively award Arizona’s electoral votes to Trump in 2024. It was an effort, one of the bill’s supporters explained, to “ignore the results of another illegally run election.”

Lake, who continues fighting for a redo of the gubernatorial election even as she runs for US Senate, is stuck in the same predicament as much of her party. Election denial might have started as an applause line, but once you exposed the conspiracy it also meant you couldn’t stop—the only way out was to keep telling the lie until you finally won.

At his office across from the courthouse, I asked Gates, who has publicly detailed his struggles with PTSD, if he had seen any indications that the fever was breaking. He replied by pointing out a recent change the supervisors had made to the chamber where they hold public meetings. In February, a group of attendees upset about the recent elections had attempted to storm the dais. Now the room has a pony barrier.

“I could post on X that I just had a sandwich, you know, and there’d be several comments that I’m a traitor,” Gates said.

A few days after the MCTEC tour, I stopped by a Republican candidate forum at a rec center next to a pickleball court in Sun City West, a sprawling retirement village 45 minutes from downtown Phoenix. The community is red, white, and very old—at one point, the emcee interrupted proceedings to ask whether anyone was missing a pair of bifocals.

Fears of stolen elections came up in almost every race, even the ones you might not expect. A candidate for Maricopa County sheriff promised that, if elected, he would put deputies in charge of transporting ballots and confiscate suspicious voting equipment. A candidate for the legislature promised to get rid of early voting. A candidate for Maricopa County attorney blamed the Republican incumbent for pursuing sanctions against election deniers. Even one of the candidates for superintendent of schools managed to bring the conversation back to “election integrity.”

The Trump campaign’s local field director, on hand to promote a get-out-the-vote program, said that Hamadeh had “supposedly” lost his 2022 race, moments before Hamadeh himself took the stage to brag about his ongoing lawsuit. Kern, whose campaign sold T-shirts bearing his mugshot, described himself as a “proud member of the 2020 electors club” and announced to the crowd that it was “time for battle.” Multiple candidates used their time to demand Richer’s firing.

When Richer spoke, following a Lake-backed primary challenger who accused him of mailing out extra ballots, he talked up his law enforcement endorsements and efforts to keep voter rolls up to date. “I want to be a resource,” he told the room.

The crowd booed.

The moderator asked him a question that he said had been picked at random: Did Richer believe the 2020 election was stolen?

Richer enunciated his response as clearly as he could.

“I do not believe the 2020 election was stolen,” he said.

The boos started up again.

Republican voters weren’t persuaded by the recorder’s promises of transparency and good faith. In July, Richer lost his primary by a little less than nine points. For the third straight election, the most competitive county in America’s most competitive state will roll the dice with someone new.

Correction, October 3: An earlier version of this story misstated the height of the fence outside MCTEC.