Pakistan is not an easy country in which to be a journalist, and it’s even more difficult to be an investigative journalist. Whether digging into real estate developments, blasphemy issues, or even the construction of a stretch of road in a small border town, it’s important for Pakistani journalists to know when to stop reporting.

This, coupled with an industry in financial trouble and limited resources, means Pakistani reporters face considerable obstacles to simply doing their work. Since 2019, Pakistan has fallen 10 points on the Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index. This year, the report noted: “No matter their ideology, political parties support freedom of the press, but they are incapable of defending it when they come to power, due to the control of the military over the country’s affairs.”

Nevertheless, the stories that GIJN features below are a testament to the courage of the members of the Pakistani press, who continue to dig despite censorship and ever more menacing red lines preventing them from reporting. One clear example of this is that two of the stories included — on threats to Pakistani-descended activists based abroad and on a flood protection scheme in Punjab province — were published on websites not currently accessible in Pakistan.

Naziha Syed Ali is a veteran investigative reporter and an assistant editor at the English-language newspaper, DAWN. Her recent reporting has focused on financial corruption, including a series on the development of Bahria Town, a gated community on the outskirts of Karachi. In this follow-up investigation, she reported that Bahria Town has been expanding — violating a 2019 Supreme Court judgment that allowed the project a specific acreage — and that the people behind the project have been both misleading the court and those who bought property in the development. She also reported that the real estate company has not paid a court-mandated fine. Syed documented her investigations using satellite mapping — showing where the development has encroached on land — on-the-ground reporting, legal documents including court land surveys, and anonymous high-level sources.

The developers have not responded to the allegations in Syed’s story. However, in court, they denied allegations of taking more land than was allocated to them in the 2019 judgment. (Read GIJN’s article on Naziha Syed Ali’s investigation into corruption in Karachi’s water supply chain.)

Crooked Path — The Turbat-Balida Road

According to Akbar Notezai’s investigation for DAWN, a stretch of road connecting two towns in Pakistan’s Balochistan province has been under construction since the 1990s. Notezai’s story delved into the history of the road’s construction, from initial approvals and funding to where it stands today. The story reports that one of the reasons for the stalled construction is embezzlement by public officials, in particular various members of the provincial assembly. Notezai spoke with anonymous sources from within the Balochistan finance department that suggest systemic financial corruption. He also used documents obtained from the finance department to show how funds have been consistently allocated for the construction of the road.

The story quoted a member of the region’s provincial assembly and former finance minister, Zahoor Buledi, who conceded that a portion of the road remains unfinished — despite being underway for almost three decades — but challenged Notezai on his assertions, claiming that the delays are due to the security situation in the area, not malfeasance of local officials.

Instagram and Misinformation

Image: Shutterstock

In October 2024, students in Pakistan took to the streets to protest the alleged rape of a female student on a women’s college campus in Lahore. As the protests grew — across the capital but also in the cities of Rawalpindi and Gujranwala — students clashed with police; several were arrested and around 28 students were injured. But when college administrators and police checked hospitals, ambulances, and CCTV footage, they found no evidence of the alleged rape; the parents of the alleged victim also denied an assault took place.

This story by BBC Urdu’s Roohan Ahmed looked into how news of the alleged sexual assault was first posted on a handful of Instagram accounts and then spread through various WhatsApp groups, prompting large-scale demonstrations. Ahmed spoke to protesting students, parents, college administrators, and law enforcement; analyzed social media; and examined reports from Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) — which traced the initial claims to 13 Instagram accounts — to explain how the misinformation spread. The FIA registered a case against 36 people for spreading misinformation, including two YouTube account owners.

Uncovering Pakistan’s Blasphemy Business

Image: Shutterstock

The Pakistan penal code outlaws blasphemy — insults to a religion or religious figures — and punishments range from fines to the death penalty. There have also been cases where those accused of blasphemy were killed in mob violence.

Recently, there has been an increase in online blasphemy accusations. An investigation by VoicePK examined First Information Reports (FIRs) filed with the police and discovered that only a small number of people were behind roughly 400 blasphemy accusations across the country. Reporting on the case of a 16-year-old boy accused of sharing blasphemous content on WhatsApp — and his father’s discovery that hundreds of other families were facing the same ordeal — revealed a common pattern, which suggested the actions of a coordinated group entrapping young men online and duping them into sharing blasphemous content. Most of the accused — many of whom are now in jail or awaiting trial — were contacted in the same way and incriminated with the same pictures or content, and the FIR complaints featured near-identical wording.

An AFP investigation into the same issue reported that many of these blasphemy cases are brought to trial by private “vigilante groups” that include lawyers and volunteers who, according to the police and rights groups, scour the internet for potential offenders. They also noted that there might be a financial motive behind the accusations.

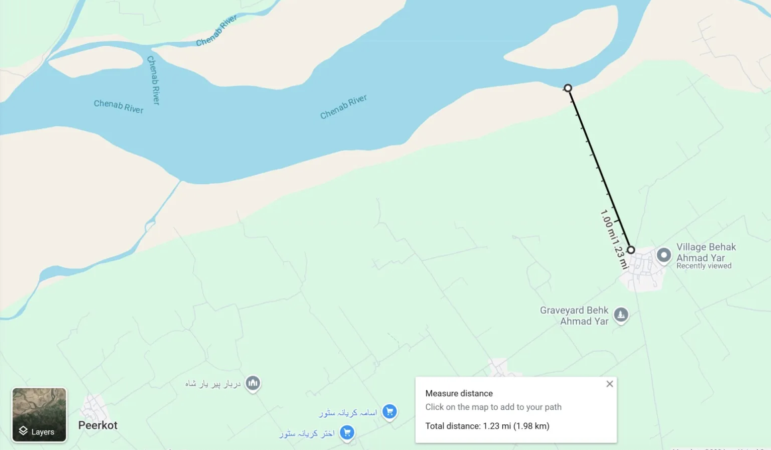

A Development Project and a Government Advisor

This story by Fact Focus reporter Amara Shah investigated details of a 480 million-rupee (US$570,000) project to create a bund — an artificial river bank that protects against flooding and erosion — along two villages in Pakitan’s Hafizabad district in Punjab province. Shah reported that the plans for the project were approved by Punjab’s caretaker government ahead of elections — to please a close advisor of the prime minister, on whose family land the bund was to be built. Shah cited the lack of approval criteria for such a project, and argued that “a caretaker government is not authorized to approve large-scale projects of this nature.” Government officials who were part of the approval process have denied any wrongdoing, and have denied it was done to benefit any particular individual.

Sanitary Workers and Exploitative Labor

This special series from the multimedia investigative platform Lok Sujag investigates the world of sanitary workers — including road cleaners, sweepers, and sewage workers — in Pakistan’s Punjab province. The series reported on the systemic issues affecting the workers, such as social stigma, poor working conditions, and drug addiction. They also noted that Punjab’s sanitary workers are overwhelmingly Christian — a religious minority often stigmatized and targeted — and how the nature of the jobs puts them under extreme duress and pressure. Entire families are caught in a loop, unable to leave the profession due to a lack of other opportunities.

This is not the first time that someone has spoken about the plight of sanitary workers, or the fact that they overwhelmingly tend to be Christian, but the series presented a holistic approach to the issue and illuminated systemic issues in ways that have not been covered before.

Harrowing Phone Calls Expose Global Campaign of Repression

Image: Screenshot, Drop Site News

Activists in Pakistan can face harassment, threats, and violence. But over the past few years, Pakistani citizens or individuals of Pakistani descent living in other countries have also become targets. This story by Ryan Grim and Murta Hussain, published by Drop Site News, examined this phenomenon through the case of Shabbir — an Australian citizen of Pakistani descent who runs a X/Twitter account focused on democratic reform in Pakistan, and who circulated high-profile petitions on human rights and Pakistan’s February election.

In March, not long after the elections, Shabbir’s Pakistan-based brother was abducted from his home. After posting about his disappearance, Shabbir received a phone call from his brother’s number in which an unidentified person could be heard allegedly beating and threatening his brother, and who called on Shabbir to stop criticizing Pakistan on social media. (The story features the harrowing audio of the phone call, which Shabbir recorded.)

The reporters do not confirm who was behind the abduction, but it puts Shabbir’s experience in the context of other cases of Pakistani activists living abroad being threatened — and discusses the rising trend of transnational repression.

Sugar Mills Default

Cutting and carrying sugarcane to send to a sugarcane factory in Punjab, Pakistan. Image: Shutterstock

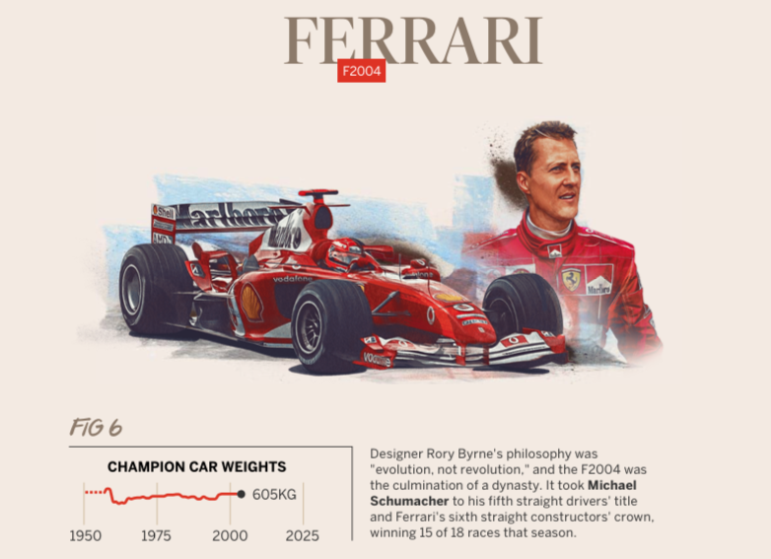

Pakistan’s sugar industry is one of the country’s most powerful, notes Profit reporter Ahmad Ahmadani — adding that almost all of Pakistan’s 91 sugar mills are owned by “household name politicians and their families.” This story explained the history of sugar mill ownership, how the system is structured, and how having the interests of such a small group disproportionately represented in government has impacted the country.

A major finding of the reporting was that — based on an audit report of the state-owned National Bank of Pakistan (NBP) — at least 25 sugar mills owned by “influential individuals with ties to the political elite” have defaulted on loans worth over 23 billion rupees (US$273 million), which are owed to the NPB. Ahmadani asserted that despite default, the debt has been largely forgiven, thanks to the owners’ connections. He also traced the direct ties between the sugar mills and their ownership and reported that these loans were granted in violation of NBP policies.