By leveraging open source tools, collaborations, and data analysis, African journalists are unearthing hidden injustices across the continent. From the exploitation of natural resources to financial corruption and the misuse of harmful chemicals, investigations have had profound impacts, led to policy reforms, and built public awareness.

As part of Africa Focus Week, GIJN hosted a webinar exploring cross-border reporting connected to Africa, with a panel of African journalists discussing groundbreaking investigations in Cameroon, Kenya, and Eswatini that had strong international links. The panel included Grace Ekpu, a documentary photographer, filmmaker, and Associated Press investigative reporter; Cynthia Gichiri, a reporter and producer with Africa Uncensored; Madeleine Ngeunga, Africa editor for the Pulitzer Center; and Micah Reddy, Africa coordinator for the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). Dinesh Balliah, director of the Wits Centre for Journalism, moderated the panel.

“More than ever before, investigative stories develop reporting strands that land far away from their points of origin,” Balliah noted in her introduction. African journalists have numerous hurdles to overcome, she added, such as financial limitations, visa and other travel restrictions, and technological barriers. Foreign reporters in Africa also encounter unique challenges that local journalists “have the skills and experience to circumvent,” she added.

“Collaborative investigative journalism, therefore, is growing in importance as a mutually beneficial tool for reporters and newsrooms keen to tell stories in or about Africa,” explained Balliah.

How AP Investigated Cameroon’s Fishing Violations

In 2021, the European Union (EU) issued a so-called “yellow card” warning to Cameroon over alleged illicit activities of fishing vessels flying the Cameroonian flag.

The “flag of convenience” system allows companies to register ships, for a fee, in a foreign country — even when there is no link between that country and the vessel. The striking increase in the number of ships carrying the Cameroon flag — but registered or managed by EU-based companies — might have triggered the action from the EU, which warned the country that it was not doing enough to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

This incident and the rapid adoption of Cameroon’s flag of convenience “sparked our interest,” explained AP journalist Grace Ekpu, who along with AP colleague Richa Syal looked at the data and found that Cameroon’s industrial fishing fleet increased from 14 to 129 vessels in four years — a 821.4% rise. Ekbu explained that the appeal for vessel owners and companies is that this system offers them minimal regulation, cheap registration fees, low or no taxes, cheap labor, and access to more shipping ports.

The investigation also uncovered, among other things, that all of the EU-linked vessels registered to Cameroon did not operate in Cameroon waters, and tracking data showed that the ships journeyed between ports in Mauritania, Angola, South Africa, and Namibia. In addition, 14 of these vessels were owned and managed by companies based in EU member states — Belgium, Malta, Latvia, and Cyprus — and lacked genuine ties to Cameroon. Why do this? Because, she explained, there is weak oversight from Cameroon’s budget-strapped fisheries authorities.

Ekbu also pointed out that this practice places “strain on artisanal fisheries,” thanks to a growing number of foreign-owned vessels competing with local fishermen.

“This investigation was a collaborative effort with Richa and a host of other AP colleagues in different countries,” Ekpu said. Their evidence-based reporting involved open source tools and databases such as Marine Traffic, IHS Maritime Database, Global Fishing Watch, and Lloyd’s List Intelligence. They also dug into public records for other IUU violations.

Months after the investigation was published, the EU issued Cameroon a “red card” for not cooperating in the fight against illegal fishing. More follow-up on the report also kickstarted conversation on reforms of the ship registration processes and stronger enforcement.

Investigating Timber Trafficking in Cameroon

Madeleine Ngeunga, the Pulitzer Center’s Africa editor, discussed a series of collaborative investigations involving InfoCongo, Le Monde, and the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network on the troubling increase in illegal logging cases in Cameroon. Ngeunga explained that she started investigating timber trafficking as a fellow for the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network, when she realized it was a global issue that would benefit from collaboration.

Reporters for InfoCongo and Le Monde spent 12 months speaking to stakeholders and loggers to reveal how corruption flourishes in Cameroon’s timber industry, and discovered that legal loggers were often involved.

They started with research to find out where the illegal activities were taking place, then pored through data that identified specific areas where forest cover changes were occurring. Painstakingly going through piles of scanned PDFs, they discovered that many companies use the logging title solely to launder timber out of Cameroon.

Nguenga stressed the difficulties of reporting on the issue: “The context is really hard. These are critical topics. Sometimes people behind the trafficking are people with power, people doing strong business… One of the most important things is to have your backup. Realizing how critical and dangerous the topic was, we knew it would be really important for us to collaborate, and to be strong together,” she added.

The investigation found that some of the companies sanctioned by the government for illegal forest exploration still retained their small-scale logging titles, which allows them to continue operating in areas not exceeding 2,500 hectares and have a one-year exploitation period, renewable up to two times.

The report also found that the companies were mining outside of the areas allowed under the small title, further piling on previous violations. This lax government oversight fueled illegal logging and helped facilitate the illicit smuggling of tropical logs to Asia; it also undermined efforts by the Cameroonian government to combat illegal logging in its forest and to protect Indigenous forest communities.

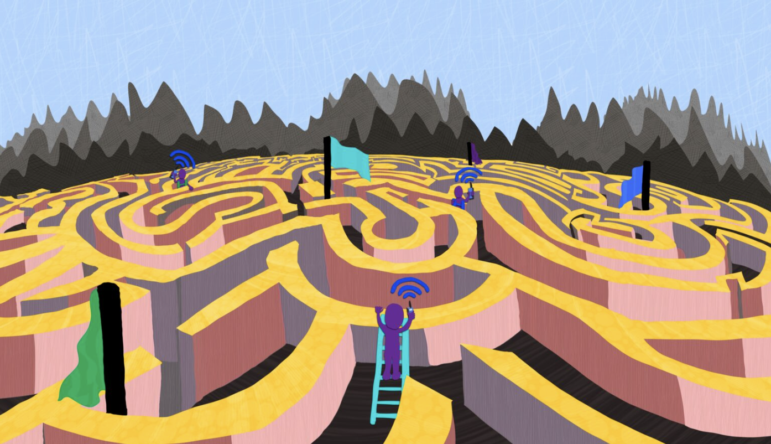

Read more about how African investigative outlets are producing complex, cross-border collaborations in GIJN’s story, Secrets, Leaks, Rivers. Illustration: Roy Blumenthal for GIJN

Investigating Pesticide Harm in Kenya

Cynthia Gichiri, of Africa Uncensored, shared her reporting on an American public relations firm’s involvement in promoting harmful pesticides, published in collaboration with Lighthouse Reports, Le Monde, the Guardian, and several other international outlets.

Gichiri explained that this story connects to Kenya because the East African country has been in a “protracted battle” against the use of harmful pesticides with carcinogenic or neurotoxic properties. She cited a report by the Route to Food Initiative (RTFI), which stated there has been an increase in the sale of hazardous pesticides in Kenya since 2023, with 76% of pesticides used there classified as hazardous.

The reporters spent months speaking to local farmers in Kenya to investigate the impact of paraquat, a harmful fertilizer, used as a herbicide during planting, that has been linked to health issues including Parkinson’s disease. The investigation connected the use of the substance, already outlawed in the United States, to a multimillion-dollar campaign by a US reputation management firm that works with a network of agrochemical industries to promote the use of harmful chemicals in various countries, including Kenya. They also investigated how such firms have spied on African anti-pesticide or anti-GMO activists, and have sponsored misinformation articles about the use of pesticides.

The reporting was underpinned by court records in the United States, where the companies were accused of concealing information about the impact of paraquat. They used PACER, a public repository for court filings, to track US court cases.

Crucially, the investigation showed how this chemical is causing irreversible health damage to the farmers exposed to it; they found a farmer who suffered from Parkinson’s, even though there was no record of the disease in his family.

Gichiri notes that agriculture is an underreported sector: “We really need, as journalists, to take seriously the role of informing and educating our audiences on consumer rights, especially in Africa,” she said, adding that one of their investigations’s sources said it was a “dumping ground” for toxic products.

“In-country collaboration” on critical issues facing the agriculture sector, and consumer issues in general, will help ensure Africans have access to quality and safe products, Gichiri added.

Following the Money in Eswatini

Micah Reddy, of ICIJ, shared his experiences working on a large cross-border investigation based on a leak of more than 890,000 internal records from the Eswatini Financial Intelligence Unit (EFIU). The leak sparked a series of articles — produced by ICIJ with various southern African investigative partners — exploring suspicious money flows connected to Eswatini, known as Swazi Secrets.

This trove of leaked documents was obtained by Distributed Denial of Secrets, a nonprofit devoted to publishing and archiving leaks, who shared them with the ICIJ, who then coordinated a team of 38 journalists across 11 countries. One of their principal tasks, explained Reddy, was to make the data accessible and manageable — and to look for a list of names and potential stories in their region.

Like other big data troves, the leak included bank records, police reports, court records, and confidential exchanges between government agencies within southern Africa. The leak also entailed information on individuals and entities suspected of involvement in illicit activity, but also included details about enablers — and companies suspected of criminal activity.

“This was a project that was too big for any one investigation, or for any one media outlet, so we had to share information,” explained Reddy. “This was especially important given the limitations of the leaks.” He explained that while the leaks were expansive, they were also limited, and the data was patchy and incomplete thanks to the circumscribed role of the EFIU.

“We ended up having to do a lot of on-the-ground reporting, and our partners had to do a lot of on-the-ground reporting, from Eswatini to Canada,” he added.

Among other angles, their investigation revealed how a gold market set up by the Eswatini government made the country a hub for regional and international illicit financial flows; the existence of a “ghost” bank; and the questionable dealings of a former president of a southern African country.

The investigation was successful through partnership and collaboration among southern African journalists, Reddy noted, citing Open Secrets, who Reddy met by chance at an African Investigative Journalism Conference and discovered had been digging into the same subjects. Together, they were able to “fill in a lot of the gaps,” he explained.

“Thanks to that collaboration, we had much fuller stories,” added Reddy.