SEOUL, South Korea — When South Koreans came out to defend democracy this week in the face of a surprise martial law declaration by their president, history was weighing heavily on their minds.

South Korea, a key U.S. ally, is the world’s 10th-largest economy and a vibrant Asian democracy in a region where authoritarianism is on the rise. But the country of 50 million people spent decades under military-authoritarian rule, with martial law frequently declared and those who resisted it sometimes killed.

“I think a lot of people were concerned about what soldiers on duty who were being deployed to implement martial law were going to do,” said Eun A Jo, a postdoctoral fellow at the Dickey Center for International Understanding at Dartmouth College. “And thankfully, this time around, we didn’t see any bloodshed.”

President Yoon Suk Yeol shocked the country Tuesday when he declared emergency martial law in a late-night television address. Lawmakers and members of the public rushed to the National Assembly in the center of the capital, Seoul, where troops were already massing.

“The division that was deployed were the folks who are trained to basically implement some of the hardest tasks vis-a-vis North Korea,” which South Korea technically remains at war with, Jo said. “So I think when they were deployed, they were under the impression that this had something to do with that. But then they ended up at the National Assembly.”

Their job was to prevent lawmakers from entering, since the legislature’s operations had been banned under the martial law proclamation.

“I think many of them felt confused by the order,” Jo said. “Some said they were embarrassed.”

Lawmakers were able to make their way in and quickly voted unanimously to nullify Yoon’s order, which he lifted early Wednesday.

As the initial shock of the events has worn off, South Koreans have called for Yoon to resign or be impeached, with tens of thousands of people expected to rally in Seoul on Saturday. A vote to impeach him is set to be held at 5 p.m. local time (3 a.m. ET).

A long road to democracy

South Korea, which was founded in 1948 after the division of the Korean Peninsula into the Soviet-occupied north and the U.S.-occupied south, experienced martial law multiple times under its first president, Syngman Rhee, who used it to suppress communists.

Anti-corruption protests forced Rhee to step down in 1960. His successor, Yun Bo-seon, was ousted the following year by South Korean army officer Park Chung-hee, who was also fond of using martial law to crack down on dissent.

Park was assassinated in 1979. His successor, Choi Kyu-hah, was ousted in a military coup by Chun Doo-hwan, who ruled for eight years.

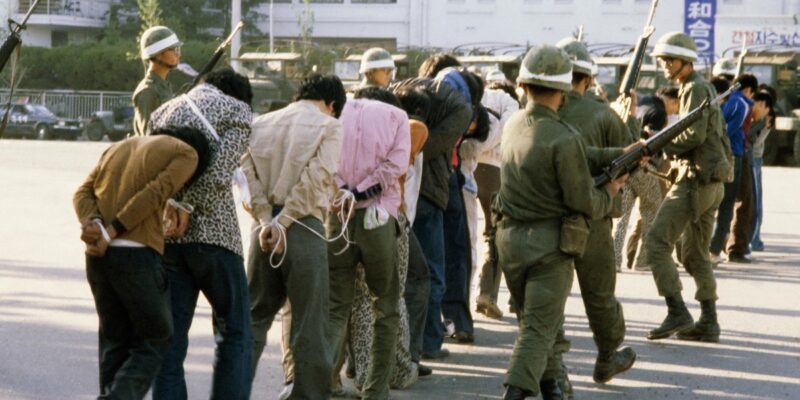

The last time martial law was declared in South Korea was by Chun in 1980. In response, a pro-democracy uprising led by students and civilians broke out in the southern city of Gwangju.

Hundreds of people are estimated to have been killed in the military crackdown that followed.

Protesters commandeer a military vehicle in Gwangju, South Korea, in 1980.Bettmann / Getty Images

The uprising was a pivotal moment in South Korean history, Jo said, that marked the country’s last attempt at democratization before it was achieved in 1987.

“The history of Gwangju is something that we grow up with,” she said.

The difference between the soldiers who were deployed to enforce martial law in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s and the ones deployed this week, Jo said, “is that these soldiers are of a different generation, and they know the history of South Korean dictatorship far better.”

Yoon may have taken a different lesson from South Korean history, said Rob York, director for regional affairs at Pacific Forum, a foreign policy research institute in Honolulu.

During South Korea’s period of military dictatorship, “there were a couple of coups that took place that were designed to break gridlock, I guess you could say, and take decisive action to shore up the country’s future,” York said. “I think that’s what Yoon was trying to replicate.”

But unlike the architects of past coups, Yoon “did not really understand that he didn’t have the kind of hold on the military,” York said, “and didn’t even have a hold on his own party in that regard.”

Yoon, who accused opposition lawmakers of obstructing the government and sympathizing with North Korea, appeared to expect that the South Korean military and the country’s anti-communist elements “would coalesce around him the way that they did for Chun Doo-hwan and Park Chung-hee before him,” York said.

Instead, protesters rushed to the National Assembly, with viral videos showing people confronting soldiers over their actions.

“I think it came as a surprise to Yoon and his supporters how quickly the Korean public turned against their decision and fought back,” York said. “That, I would say, demonstrates the determination of the Korean public not to go back to that period in history.”

Soldiers leaving the National Assembly in Seoul on Wednesday after lawmakers voted to reject President Yoon Suk Yeol’s martial law declaration.Woohae Cho / Bloomberg via Getty Images

The U.S. role in military rule

Among those caught off guard this week was the Biden administration, which said it was not notified about Yoon’s plans in advance.

Throughout the week, U.S. officials have repeatedly reaffirmed the “ironclad” nature of the U.S. alliance with South Korea, which it views as an important bulwark against North Korea, China and Russia, and which hosts almost 30,000 American troops.

The U.S. military has had an almost continuous presence in South Korea since the end of World War II, even ruling the country from 1945 to 1948. The American troops there today serve as a deterrent against aggression from nuclear-armed North Korea.

Over the years, the U.S. has been accused of siding with South Korean dictators over democrats.

Historically, “whenever South Korean authoritarian leaders wanted to declare martial law, they typically sought at least some kind of tacit approval from Washington,” Jo said.

Historians say the U.S. stood by during the deadly South Korean military response to the 1980 Gwangju uprising, for example, for fear that the protests might spread to other cities and invite North Korean intervention.

In 1964, Jo said, when there were nationwide demonstrations against the normalization of relations with Japan, the U.S. agreed to release command of an infantry division that was deployed to enforce Park’s martial law, according to declassified documents.

The events in South Korea this week also brought to mind more recent history, said Jean H. Lee, an adjunct fellow and northeast Asia expert at the East-West Center research organization in Honolulu.

Another conservative president, Park Geun-hye — the daughter of Park Chung-hee — was impeached in 2016 after a series of mass candlelight vigils. She was later sentenced to 24 years in prison on corruption and other charges before being pardoned in 2021 by Yoon’s predecessor, President Moon Jae-in.

South Koreans “have a long culture and a long history of demonstration,” Lee said, “and they saw in 2016 that they can have an impact and sweep a president out of power.”

Stella Kim reported from Seoul and Jennifer Jett from Hong Kong.