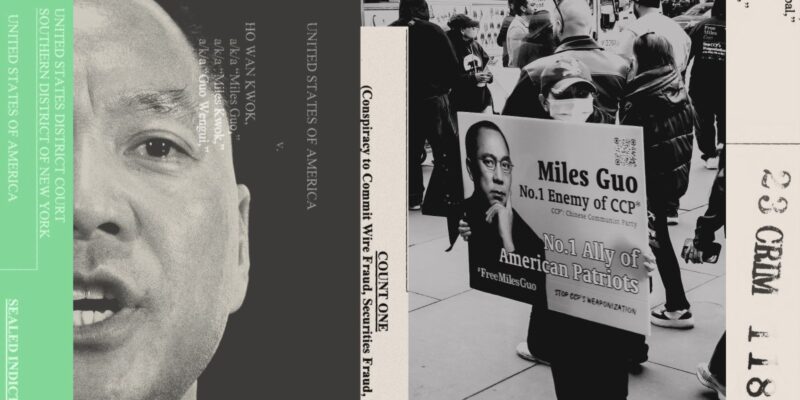

Lawyers for Guo Wengui—the exiled Chinese mogul on trial in New York for allegedly stealing hundreds of millions of dollars from investors in business ventures he launched—rested their case this week with a seeming non-sequitur.

The defense’s last witness was George Higginbotham, a former Justice Department lawyer who pleaded guilty in 2018 to conspiracy to make false statements to a bank. Higginbotham did that as part of an illegal lobbying conspiracy that included efforts to pressure the Trump administration to extradite Guo to China, where the mogul faces various criminal charges, including fraud, bribery and rape.

Higginbotham testified that he and his conspirators—including Elliott Broidy, a former top fundraiser for Donald Trump, and Pras Michel, a former member of the Fugees for whom Higginbotham was moonlighting as a lawyer—received around $100 million for their illicit influence efforts and said that he once met with the Chinese ambassador about Guo in an effort to advance the scheme.

But Higginbotham did not say a word about the extensive fraud case that prosecutors have laid out against Guo. That case includes videos in which Guo falsely guaranteed fans that he would not allow them to lose money investing in his business activities, bank statements and testimony from cooperating witnesses indicating that Guo moved investor funds into accounts he controlled, and various evidence that Guo then used the funds to buy stuff like a $26 million mansion, a $4.4 million Bugatti, and two $36,000 mattresses.

Higginbotham, who knew nothing about that case, could offer no information related to the charges Guo faces. His appearance highlights a strategy by Guo’s lawyers to instead play up their client’s self-styled image as a critic of the Chinese Communist Party, and to point out that Chinese agents have made extensive efforts to silence him.

During the trial, Guo’s lawyers have missed no chance to brandish a stipulation they reached with prosecutors, which says that “in 2017, a US law enforcement agency assessed that Mr. Miles Guo was the highest priority of China repatriation efforts” aimed at CCP critics within the Chinese diaspora.

Guo lawyer Sidhardha Kamaraju cited the stipulation repeatedly during the first portion of his summation on Wednesday. Kamaraju argued that CCP targeting of Guo and the scheme Higginbotham took part in gave Guo “reason to believe that the CCP could influence DOJ employees.”

Last week, the defense elicited testimony from Paul Doran, a corporate risk adviser who testified as an expert on China. Doran said that Guo, in broadcasts in 2017, had “exposed corruption at the highest levels in China, which is extremely embarrassing for President Xi [Jinping] and his close circle.”

“In my professional opinion, Mr. Guo is public enemy number one in China,” Doran said.

This focus on the Chinese government’s dislike of Guo is, arguably, responsive to the prosecution’s contention that the anti-CCP movement Guo built with former Trump adviser Steve Bannon was effectively a con—a means of winning the trust of CCP-hating Chinese emigres in order to fleece them. One of Guo’s lawyers, Sabrina Shroff, has also suggested that Chinese hacking efforts explain why Guo created numerous bank accounts. Prosecutors say it was for money laundering.

Another reason to highlight China’s beef with Guo may be to hint at a claim that Guo’s supporters have made since his arrest last year: that the Justice Department’s prosecution of Guo is itself the result of nefarious Chinese influence efforts.

Judge Analisa Torres has barred Guo’s team from making this argument in court, ruling that the theory is unsubstantiated and prejudicial. And though Higginbotham’s illegal lobbying had nothing do with his DOJ day job—he was in fact fired as result of his moonlighting—prosecutors and Torres have accused the defense of hoping that Higginbotham’s onetime employment at the department now prosecuting Guo will confuse jurors.

“Clearly bringing that up is merely a rather clumsy way of trying to link the prosecution in this case with corruption and the Chinese government,” Torres said during a sidebar with attorneys on Monday.

Guo’s lawyers did call witnesses aimed at undermining aspects of the government’s case. And Kamaraju argued in detail Wednesday that prosecutors have not proved Guo committed fraud. But much of the defense’s focus has been on asserting that Guo’s attacks on the CCP were sincere. Shroff, in the defense’s opening statement, called this campaign “the essence of [Guo’s] entire being.” That assertion tracks the biography Guo has promoted since 2017 and may have pleased the scores of his supporters who packed the Manhattan courtroom throughout the trial.

The problem, though, is that Guo’s dispute with the CCP, the centerpiece of his defense, is not necessarily exculpatory. Guo could be a real target of Chinese spies while also being a fraud. Guo’s lawyers might lack better options, but they are left banking on the hope that at least some jurors find the freedom-fighter story they are selling so appealing—and perhaps so confusing—that they overlook the mountain of the evidence against Guo.

Federal prosecutors, who are presumably eager to keep their sprawling RICO case as simple as possible, have regularly responded to defense efforts to position Guo as an uncompromising CCP critic by returning jurors’ focus to his alleged crimes.

As a result, the defense, for much of the seven-week trial, has had fairly free reign to present a simplified, and highly dubious, version of their client as a lifelong dissident. Jurors, all of whom attested they knew nothing about Guo’s case before the trial, remain presumably unaware of years of robust questioning of “whether Guo is, in fact, a dissident or a double agent,” as federal Judge Lewis Liman—presiding over a lawsuit in the same courthouse as Guo’s current trial— put it in a 2021. At the time, Liman concluded that the “evidence at trial does not permit the Court to” resolve that question and that “others will have to determine who the true Guo is.”

Last year, prosecutors filed a heavily redacted motion revealing that federal agents in 2019 executed search warrants against Guo that resulted in the seizure of “more than 100 electronic devices and documents” from a safe in one of his homes. That search was not related to the fraud case for which Guo is currently on trial, the filing said. And according to a former lawyer for a Guo codefendant, it was carried out by “counterintelligence agents from the FBI”—an indication that the feds may have suspected Guo of ties to foreign espionage. But prosecutors have not mentioned that raid in open court. Nor have they pointed to lawsuits alleging Guo is CCP agent, a charge Guo denies.

But as the defense made their case over the last few weeks, prosecutors have gone further than they had before in noting that the truth is more complicated than Guo’s attorneys suggest, and have even highlighted some of the evidence of Guo’s ties to Chinese intelligence.

On Tuesday, Guo’s lawyers used Higginbotham’s testimony to introduce transcripts from 2017 phone calls in which Liu Yanping, a top official in China’s ministry of security, appeared to threaten to arrest Guo’s family members in China in a effort silence Guo’s attacks on the CCP, or convince him to return to China.

But the calls also included discussion of an “agreement” between Guo and Liu in which Guo promised to would limit his criticisms to certain CCP officials, notably excluding Xi. On cross examination, Assistant US Attorney Juliana Murray pointed to a portion of one of those calls in which Guo said he “just wanted to protect my money, my life, and my wealth.” He added that “I still love the country and the party.”

Guo has said these statements were coerced. Still, about three months later, he sent a letter to Communist Party leaders in which he offered to “desist from revealing information” if they dropped efforts to extradite him and unfroze his assets. “I will definitely devote my life to…uphold[ing] the core beliefs of Chairman Xi, and sacrifice my everything for Chairman Xi,” Guo wrote.

Earlier in the trial, on June 3, Assistant US Attorney Ryan Finkel also brought up Guo’s past ties to another senior Security Ministry official, named Ma Jian. Ma’s influence, as Mother Jones and others have reported, appears to have helped Guo make a fortune in Chinese real estate.

In his summation, Kamaraju suggested that Guo fled from China in 2014 due to his criticism of the CCP. That’s not true. Guo fled China due to Ma’s 2014 arrest on allegations that included accepting bribes from Guo. (Guo has denied bribing Ma and all other charges he faces in China.)

But Guo’s ties to Ma suggest Guo was a beneficiary of the corrupt security apparatus he later faulted, part of a faction that lost out in an internal CCP power struggle. Finkel hit that point while questioning Doran.

“To be a billionaire in China requires some connections or help from the CCP, right?” Finkel asked Doran, the defense’s China’s expert. Doran agreed.

“You know Miles Guo lent money to Ma Jian’s sister, right?” Finkel asked Doran. “Ma Jian’s sister then spent that money to buy properties…Then Guo bought back those properties from Ma Jian’s sister. Did you know that? And this was designed so Ma Jian can make a profit.”

Doran said he knew none of that.

Finkel also used Doran’s presence on the stand to ask about a notable item FBI agents found during a search of Guo’s home last year: a box with the logo of the People’s Liberation Army, the Chinese military, on it. The defense had previously introduced a photo of Lieutenant General Bi Yi, head of the PLA branch purportedly responsible for cyber spying—part of their effort to highlight China’s targeting of Guo.

Finkel showed the jury a picture of the logo on the box from Guo’s home alongside a picture of the logo on Bi’s hat. They matched.

Shortly after this, though, the government returned to their main argument. Doran had testified that he was targeted by Chinese agents while living in China. Noting this, Finkel asked the witness if he “ever raised money by making false promises online” or “committed fraud.” Doran said he had not.

“Being targeted by the CCP doesn’t give you license to do those things, does it?” the prosecutor asked.

“No,” Doran said.