The US Conference of Catholic Bishops, which creates policies for the church in the United States, formally apologized on Friday for the church’s role in traumatizing Native American children at boarding schools until the mid-1900s. It’s “the most direct expression of regret to date” by church officials for forcibly assimilating Indigenous kids into white culture, according to the Washington Post, whose investigative reporters recently documented the widespread sexual abuse by priests and nuns at these schools.

“The family systems of many Indigenous people never fully recovered from these tragedies, which often led to broken homes harmed by addiction, domestic abuse, abandonment and neglect,” the bishops said in a 56-page document, which came after decades of attempts by Native Americans to demand accountability from the US government and the Catholic Church. There were more than 500 schools in the United States, and 84 of them were operated by the church or its religious affiliates, according to the bishops’ document.

Photographer Daniella Zalcman, who spoke with Mother Jones about images she took of boarding school survivors in Canada, said the US government “invented” the playbook for harming children at these facilities in the late 1800s:

A government employee, called an Indian agent, would show up on reserves and in Native communities, and effectively kidnap all of the kids under the age of 15—some were as young as two or three. Once they got to school, they were forced to wear Western clothing, their hair was often cut off, and they were punished if they spoke their own languages or practiced their own cultural traditions. There was rampant physical and sexual assault. In extreme cases, there was sterilization and medical testing.

Tens of thousands of Native kids were sent to these schools in the United States. The US Department of Interior estimates that at least 500 of them died there.

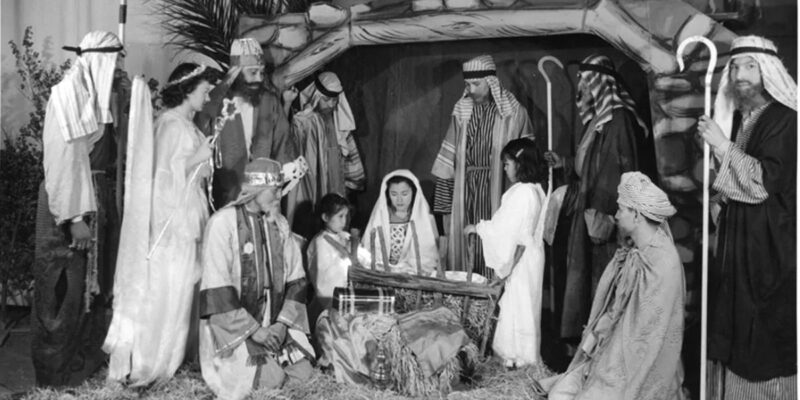

Cliff Trafzer, a professor of American Indian History at the University of California-Riverside, told my former Mother Jones colleague Maha Ahmed that the schools were “an attempt to destroy that which was Indian and re-create people in the image of White America.” He previously worked at one of these schools and co-authored a photo book about it, which shows boys getting short haircuts, the mandatory style, and girls posing with Santa during a Christmas party; kids generally stayed on campus to celebrate Christmas with their boarding school “family.”

“We want our culture back. We want our language back. We want our ceremonies back. We want our lives back.”

The bishops’ apology on Friday did not refer specifically to sexual abuse, even though the Post found at least 122 priests, sisters and brothers at 22 Catholic-run boarding schools who were later accused of sexually abusing Native American children under their care. “The Church recognizes that it has played a part in traumas experienced by Native children,” the bishops wrote.

They added later, “These multigenerational traumas continue to have an impact today, one that is perpetuated by racism and neglect of all kinds. Through our listening sessions, we heard that many Indigenous people feel unaccepted by and unwelcomed in society and even the Church.”

Some Native Americans told the Post that they appreciated the gesture but wanted more from the church: “It would be more meaningful to people if the pope issued an apology himself,” said Warren Morin, whose grandfather and other relatives attended the Catholic-run St. Paul Mission and Boarding School in Montana. In 2022, Pope Francis apologized for the church’s role in “forced assimilation” in Canada, but he has not spoken out about it in the United States.

Photographer Zalcman shared portraits of survivors with Mother Jones and spoke with them about their memories. Here’s Pat Pumpkin Seed, who attended Holy Rosary Mission from 1949 to 1960.

“I got whipped constantly in school. Whipped for messing around in church, whipped for not praying, whipped for speaking Lakota with my brother. I always thought that was so stupid. All I want—all the Lakota have ever wanted—is to be allowed to be ourselves. We want our culture back. We want our language back. We want our ceremonies back. We want our lives back.”

Here’s Wanda Garnier, who attended the same school from 1958 1963:

“For years afterwards I’d wake up in a cold sweat, always from the same nightmare. The nuns were coming to take me back. Mother Edeltrude was standing over me and telling me we had to stay there the rest of our lives…Those women treated us like we were savages who had to be civilized. I thought we were pretty civilized, but I guess not in their books.”

And Lisa Schrader, who attended St. Joe’s Indian School from 1974 to 1979 and Red Cloud Indian School from 1979 to 1982, spoke on the importance of acknowledging wrongdoing:

“You know, healing requires acknowledgement. And when we were taken away from our homes and we lost our language and we lost our culture and we lost our identity, no one ever told us, ‘Welcome home. I’m glad you made it back.’ People need that, and they haven’t gotten that.”