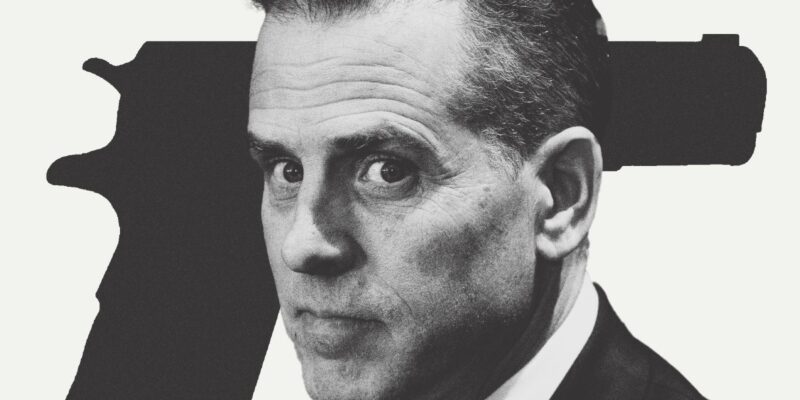

On June 3, jury selection for the federal trial of President Joe Biden’s son Hunter on gun charges is expected to begin. Hunter Biden allegedly lied about past drug use when purchasing a gun in 2018, during a period in which he has since shared that he was struggling with crack cocaine addiction. He has pleaded not guilty.

The debate around gun control and mental health is very heated in the US, especially in conversations about mass shootings. Research does show that there is no link between mental illness and mass shootings, but gun-related suicides are on the rise, especially among men.

Biden’s case opens the question of whether and when someone with a history of mental illness, including addiction, should have their Second Amendment rights taken away. A fairly recent federal court ruling, Tyler v. Hillsdale County Sheriff’s Department, could offer some insight.

“If [Hunter Biden] actually lied, that suggests arguably a greater level of culpability.”

In 2016, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, which generally covers the Midwest, ruled that someone who has been “adjudicated intellectually disabled” or “committed to a mental institution” couldn’t be barred outright from owning guns on those grounds alone. The case surrounded a Michigan man, Clifford Tyler, who was permanently barred from owning a gun because he had been institutionalized once, 25 years prior, due to a risk of suicide

I spoke with Dr. Paul Appelbaum, Columbia University’s Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law, and former president of the American Psychiatric Association, about the Tyler decision, Biden’s case, and psychiatric ethical dilemmas at the intersection of gun ownership and mental illness.

What did the Tyler case establish when it comes to gun ownership and having a history of mental illness?

There’s a list of conditions that result in exclusion from being able to legally possess a firearm, and one of those exclusions is involuntary admission to a psychiatric facility. But Tyler was, by virtue of that exclusion, entered into the national database, and unable to purchase a firearm based on a hospitalization that had occurred 25 years before.

The act that created the NICS [National Instant Criminal Background Check System] created a requirement for centralized record-keeping with regard to who was excluded, and a provision that allows the restoration of firearms rights at the federal level. But in the early 1990s, Congress barred the expenditure of any appropriated funds to implement that process.

So there’s essentially no mechanism to go to the federal government and say, I want my firearm rights back. States not only can set up a process for restoration of firearm rights, but under what’s called the NICS Improvement Act, they were actually incentivized to do that. Michigan, where the Tyler case came from, was one of those states that had no mechanism for restoration of firearms rights.

In his 70s by now, and according to any conceivable measure, at very low risk of committing violence with firearms, nonetheless, Tyler couldn’t purchase [one]. The federal district court disagreed with that argument, saying, No, the state has a sufficient interest in keeping people who have ever been involuntarily hospitalized from ever obtaining a gun.

The Sixth Circuit disagreed. [It] said, No, there’s got to be some mechanism in place to allow people to at least make an argument that they are no longer so situated as to present a risk, and therefore they should be allowed to purchase a firearm.

What ethical dilemmas are involved in deciding that someone shouldn’t have a gun due to a history of mental illness, including potential substance abuse?

Beginning in 1968, federal law established these exclusionary criteria, but there was no centralized mechanism for knowing who met any of [them]. Federally licensed gun dealers were left taking the person’s word for it. In the ’90s, when gun violence was heightened, Congress authorized the establishment of a centralized registry, and that’s the NICS.

There haven’t been data breaches to my knowledge, and moreover, if you go to a gun dealer and try to buy a firearm, the gun dealer has to query the NICS. In some cases, they query a state-level database. When an answer comes back, that this person is disqualified, because they’re in the NICS, it doesn’t reveal to the gun dealer, for example, [that] you use controlled substances, or you were involuntarily hospitalized. Now, that’s not to say—you know, we all know that there’s no database that’s 100 percent secure, but so far that has gone well.

When you’ve got a process for restoring gun rights, at some point down the road, these will frequently involve evaluation by a psychiatrist or another mental health professional to assess the extent to which an individual remains sufficiently dangerous to themselves, or to other people, that it would be unwise to restore their gun rights.

There are no good assessments of approaches that provide certainty with regard to a person’s likelihood of using a gun in an inappropriate way in the future, so mental health professionals are often in a difficult situation.

Could someone’s recent misuse of drugs, as with Hunter Biden, be a reason to take away gun rights—given that the court seemed to suggest a ban based on past mental health issues would be unconstitutional?

Another one of the federal exclusion criteria is the following, in addition to involuntary hospitalization: any person who is an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance.

So as I understand the charges in the Hunter Biden case, the government is alleging that he was, at the time that he purchased a firearm, an unlawful user of a controlled substance, and therefore was not legally entitled to purchase that firearm, even if he was not listed in the NICS as being ineligible. If he actually lied, that suggests arguably a greater level of culpability than if he was disqualified but never was asked about it.

Both Clifford Tyler and Hunter Biden had a documented mental health history. Could someone’s fear of losing their gun rights deter them from seeking mental health treatment?

I think that’s a real concern. In most states, the only people who are reported to the NICS are people who have been involuntarily hospitalized, and in most states that doesn’t include short-term emergency detentions.

Nonetheless, we have heard concerns within psychiatry, particularly in parts of the country where gun ownership appears to be an essential part of a person’s identity—particularly a man’s identity—that people at least say that they would not seek mental health treatment because of this concern. When push comes to shove, how much of a role that actually plays in keeping people from treatment is not at all clear.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.