The mothers of ModernAdoptionPlans.org have a message for women who find themselves unexpectedly pregnant: You, too, can turn this difficult time into a rewarding experience by relinquishing your baby for adoption.

In glossy videos, they tell their stories. They found themselves in crisis. Many considered abortions before deciding on adoption. It was a painful choice, but it was the right choice.

“This is one of the greatest things a parent could ever do,” says Adrianne, a Black birth mother, from a sun-filled loft. Sarah, a white birth mother, speaks to us from what looks like a church. “I didn’t choose what was best for me. I chose what was best for him,” she says.

Billboards, radio ads, and TV commercials across Texas urge residents to visit the website. In addition to the videos, Modern Adoption produced a resource guide where readers can find adoption agencies and crisis pregnancy centers, which are known to spread misinformation and push adoption. But nowhere does the site mention that the campaign is part of the multimillion-dollar, taxpayer-funded state program to dissuade women from having abortions.

The goal of Modern Adoption, according to a 2022 state report, is to “raise the profile of adoption and present it as an equally viable and acceptable alternative for unwanted pregnancy, with the intent of reducing the number of abortions in Texas.” Funding comes from the state’s Thriving Texas Families program, formerly known as Alternatives to Abortion. When Texas Pregnancy Care Network, the umbrella organization that distributes the funding, proposed the project just weeks after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the organization noted that “adoption is going to be needed more than ever.”

The goal of Modern Adoption, according to a 2022 state report, is to “raise the profile of adoption and present it as an equally viable and acceptable alternative for unwanted pregnancy, with the intent of reducing the number of abortions in Texas.”

Texas’ campaign is unique in its scale, but not its message: In the two years since the Dobbs decision, politicians and organizers in states with restrictive abortion policies have doubled down on promoting, incentivizing, and expediting adoption. Some states offer payments or tax credits for new adoptive parents. Some focus on shortening the time period before a birth mother can sign away her parental rights or change her mind about placing her child for adoption. More than a dozen states this year have heard legislation to install baby boxes, which can be installed outside places like fire departments and hospitals and which, in theory, give parents a legal and anonymous way to surrender their infants. Many states, like Texas, have increased funding for Alternatives to Abortion programs by millions of dollars.

Conservatives have long embraced adoption as one such alternative, allowing women to avoid the “consequences of parenting and the obligation of motherhood,” as Justice Amy Coney Barrett suggested during the Dobbs arguments. Liberals embrace adoption, too—particularly as a way to build families regardless of sexual orientation or race.

But some adoption experts warn that the policies and campaigns gloss over a painful reality: Many women only turn to adoption when they feel they have no other choice. Gretchen Sisson, a sociologist at University of California–San Francisco, interviewed more than 100 birth mothers for her recent book, Relinquished: The Politics of Adoption and the Privilege of American Motherhood. Most of the women wanted to parent their infants but ultimately relinquished their children because of financial constraints. “We’re never actually listening to what people in these situations need,” Sisson says. “What they say they need is a safety net. What they say they need is a crisis response so that they can raise their kids.” (States with abortion bans are less likely to have such safety nets, including Medicaid expansion, paid parental leave policies, and direct cash assistance for poor families.)

Texas, Indiana, and Louisiana are among the states with total abortion bans that have taken taxpayer-funded approaches toward promoting adoption. These initiatives are doing more than simply connecting expecting mothers to adoption resources: By framing adoption as a brave, empowered choice, they’re helping solve a critical messaging problem for the anti-abortion movement, which has faced significant backlash in the wake of Dobbs for taking away agency from pregnant women.

“The anti-abortion movement has really fought to repackage themselves as benevolent actors,” says Ashley Underwood, director of abortion rights group Equity Forward. “They’re looking to promote their answers to a problem they have created by restricting access to reproductive healthcare services.”

Texas: Targeting single women who “skew African American & Hispanic”

It’s no coincidence that the first video on the Modern Adoption site features a Black birth mother. The project, launched in the fall of 2022 with $2 million in state funding, targets women with “the highest incidence of unplanned pregnancies”: specifically, single women who “skew African American & Hispanic” and come from low-income households, according to a project proposal obtained by the Houston Chronicle.

The proposal spells out the hurdles to reaching this audience. “Due to cultural ties, many in the Black community have strong opinions on adoption. They may say that ‘we don’t do that’ with our children,” it reads. It also proposes solutions: The messaging should “inspire, not lecture (which shows to be more effective with low-income minority audience).” The campaign would be hypertargeted, serving ads in places with a higher likelihood of “at-risk behavior,” like particular schools, churches, shelters, bus stops, and malls. “For example, through our mobile ad partner we will serve ads on mobile apps to young women who frequently enter and leave high schools in specific high-risk areas,” the proposal notes. To facilitate this ad targeting, the project contracted the media giant iHeart Media and the adoption promotion nonprofit BraveLove. (Modern Adoption representatives didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

The campaign appears to have been incredibly successful. The radio, TV, and mobile ads campaigns have each left millions of impressions. A survey last year found that, after seeing a Modern Adoption ad, 78 percent of women ages 16 to 20 indicated being more likely to consider adoption. Last year, the Chronicle reports, the state allocated another $4 million to continue the campaign through 2025.

Perhaps the most telling part of the Modern Adoption website is its FAQ section, which describes adoption as a woman making a “strong, brave, loving, selfless and responsible decision when her baby needs it most.” It repeatedly touts the benefits of open adoption, in which birth parents stay in contact with their child and the adoptive parents. A birth mother, it reads, will receive “as much information and contact with the family and child as she feels is right for her.” It’s not until much further down the page that the site acknowledges that open adoption agreements are not legally enforceable in Texas. At any time, adoptive parents can decide to limit or cut off contact altogether with birth mothers.

Indiana: Home of the “ministry that is literally saving babies in boxes”

When an infant is surrendered into a baby box, an alarm sounds, and first responders arrive within minutes. Often, soon after that, Monica Kelsey takes to TikTok.

Kelsey is the founder and CEO of Safe Haven Baby Boxes, the company that provides the vast majority of the nation’s baby boxes. On TikTok, where Kelsey has more than 800,000 followers, she posts videos of herself calling her team on speakerphone from wherever she happens to be—a car, a beach chair, an office—to share the news. “Guess what?” she says, with a knowing grin. “We got another baby!”

@safehavenbabyboxes We got another baby❤️ #Monicakelsey #safehaven #safehavenbabyboxes #babyboxlady #babyboxladyofamerica #bekind #babysaved #babybox #newmexico #ontheroadagain #2024

Safe Haven Baby Boxes has a righteous goal: to prevent infant abandonment by providing safe, legal places for mothers to anonymously surrender babies, who are typically put in the foster system or placed for adoption. Since the organization installed the first baby box, at a fire department in eastern Indiana in 2016, more than 200 boxes have been installed in at least 15 states, almost all of which have restrictive abortion laws. This year, another 15 states have introduced baby box-related legislation, reports Stateline.

The work is personal for Kelsey, who was adopted after being abandoned as an infant, and describes herself as “the front runner in this ministry that is literally saving babies in boxes.” More than half of the boxes are in Kelsey’s home state of Indiana, where the state’s 125th baby box was installed at a fire department earlier this week. Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch spoke at the event to unveil and bless the box.

These “blessing ceremonies” are often covered by local news outlets with heartwarming optimism. So is the broader baby box movement: A recent glowing Washington Post article detailed the adoption of a surrendered infant, complete with photos of the baby celebrating his first birthday at the fire station where he was left. Such stories are often told from the perspective of first responders or adoptive parents, seldom acknowledging the crisis a birth mother would need to be in to consider surrendering her infant in a box.

For all the publicity, baby boxes aren’t used all that often. Since the first box was installed eight years ago, 47 babies have been surrendered in the boxes, according to the organization’s website. Their rare use may be partly due to the fact that, before baby boxes came along, every state already had a Safe Haven law, which allow birth parents to legally and anonymously surrender infants at places like hospitals. An estimated 4,500 babies have been relinquished under Safe Haven laws since the first law passed in 1999. (Unlike baby boxes, which involve no interaction with other people, a traditional safe haven surrender involves a handoff of a baby to another adult.)

Each box costs roughly $20,000 to install, along with a $500 annual service charge. Indiana lawmakers authorized $1 million to install and promote baby boxes in 2022.

The infrequent use of baby boxes hasn’t stopped states from pouring money into installing more of them, reports Stateline. Each box costs roughly $20,000 to install, along with a $500 annual service charge. Indiana lawmakers authorized $1 million to install and promote baby boxes in 2022. A recently introduced bill in Tennessee would set aside $2 million to install a “newborn safety device” in each of the state’s 95 counties.

“This rescue narrative is what’s driving it,” says Laury Oaks, a professor of feminist studies at University of California-Santa Barbara. Oaks is among the critics who argue that baby boxes amount to pro-life virtue signaling. Baby boxes are doing an important job, even if they’re not often used: turning unplanned pregnancies into feel-good stories. “I see it as a high visibility branding situation,” says Oaks. “A marketing move.”

(Kelsey and Safe Haven Baby Boxes declined to respond to multiple requests for comment.)

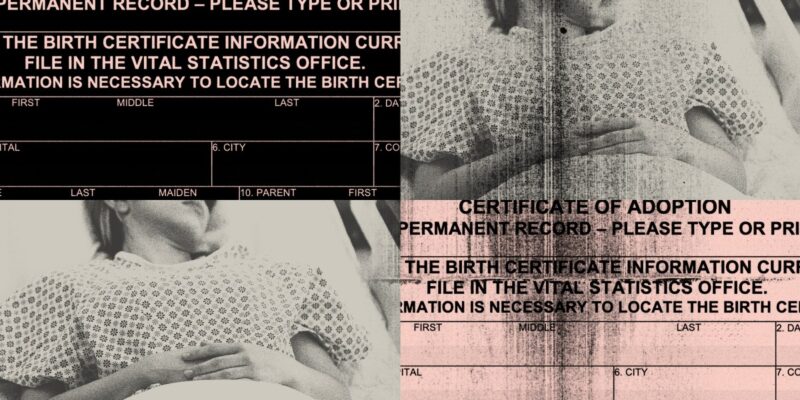

Many adoptees are critical of baby boxes, too. The boxes market themselves on anonymity; billboards reading, “Surrendering your newborn at a fire station delivers…No Shame No Blame No Names” lead mothers in crisis to the organization’s hotline. But that anonymity means adoptees won’t have a record of their birth families or medical histories, says Gregory Luce, founder of the Adoptee Rights Law Center. In Indiana, there’s now even less of a paper trail for adoptees: Policymakers passed legislation last year that allows first responders to contact adoption agencies directly, bypassing notifying the state of the surrendered infant altogether. Lawmakers say that the policy removes a layer of bureaucracy, but critics argue that such policies enable even more secrecy in an already opaque industry.

That doesn’t seem to concern Kelsey, who on TikTok often thanks the birth mothers who surrendered their babies, calling them “selfless” and “heroes.” The businesses’ website echoes this sentiment, greeting visitors with “YOU ARE NOT ALONE” and “YOU ARE BRAVE.”

But, as with the Modern Adoption campaign, one is left wondering where the line is between compassionate and calculated. Once in a while, Kelsey’s tone about birth mothers hardens. Responding on TikTok to critics who suggest that the money spent on baby boxes would be better spent supporting birth mothers, Kelsey said, “There are parents out there that should never be parents. They’re crappy parents to the kids that they have.” She adds, “I said it. I own it. It’s the truth.”

Louisiana: “This is only the beginning”

In 2018, Louisiana state representative Rick Edmonds stood in the rotunda of the state capitol, beaming at a crowd of people holding “I <3 adoption” signs. They were celebrating the passage of the Adoption Option Act, which directed the state to create a website connecting pregnant women to adoption agencies and other resources. The website frames adoption as “heroic” and “the best parenting decision for your child.” A separate tab is devoted to stories about women who regretted having abortions.

“This is only the beginning,” said Edmonds, a conservative pastor at the same church where House majority leader Mike Johnson serves as a deacon (the two are reportedly friends from their pro-life work). “We’re going to have multiple opportunities in the days ahead, the years ahead, to make sure that we model legislation that brings honor to the Lord, honor to our state, honor to our families, and honor to children that can have an opportunity to have a great and prosperous life.” He concluded with what has become his tagline of sorts: “Whenever you choose life, it’s always right.”

In the years to follow, Louisiana has become a pro-life, adoption-promoting incubator of sorts, inspiring and being inspired by legislation in like-minded conservative states. (In 2021, Arizona passed its own variation of the Adoption Option legislation; its health department website copies its FAQ section directly from Louisiana’s.) Lawmakers in Louisiana created tax credits for adoptive parents, increased funding for crisis pregnancy centers, and cracked down on alleged adoption fraud.

Louisiana has become a pro-life, adoption-promoting incubator of sorts, inspiring and being inspired by legislation in like-minded conservative states.

In June 2022, just days before the Dobbs decision came out, Louisiana passed legislation sponsored by Edmonds requiring health education for high school students to include information about “the benefits of adoption to society” and “the reasons adoption is preferable to abortion.” Critics say that the law amounts to little more than lip service: In Louisiana, sex ed isn’t required to begin with, and state law has long prohibited curricula from including information about termination of pregnancy. “The fact that young people are allowed to receive such an incomplete, inconsistent education, and now they want to throw in the word ‘adoption’…It feels like pandering,” says Brittany McBride, director of Advocates for Youth, a nonprofit devoted to bettering sex education. (Edmonds didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

Nonetheless, a year later, similar legislation had made its way to Arkansas, where a bill sponsored by the Arkansas Right to Life mandated that public school students grades 6-12 receive an hour of adoption awareness education at the beginning of each school year. Like Louisiana, such awareness must include information about “the benefits of adoption to society” and “the reasons adoption is preferable to abortion.” This year, West Virginia lawmakers introduced a bill with the same language.

Now, Louisiana policymakers are pushing to increase funding for the state’s Alternatives to Abortion program, from $1 million to between $3 and $5 million. Recently introduced legislation proposes that a single, yet-unnamed nonprofit direct the funding toward programs that “promote childbirth instead of abortion.” The Louisiana Illuminator reports that one person interested in leading the program is John McNamara, who for years ran the Texas Pregnancy Care Network, which, among other things, runs the Modern Adoption campaign. In a Louisiana Senate health committee meeting about the bill in March, McNamara noted that Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska had passed similar legislation.

“The program has been exceedingly successful,” McNamara said. He added, “By passing this bill, you will see the number of providers around the state grow exponentially.” For every Louisiana mom, “there is help and support around the corner.”