A year and a half after Mother Jones exposed how Oklahoma courts were imprisoning mothers for longer than their abusers, state lawmakers passed a bill that could allow some of those mothers’ sentences to be shortened. But this week, Gov. Kevin Stitt vetoed the legislation.

In an award-winning investigation in 2022, I told the story of Kerry King, a mom in Tulsa who got 30 years in prison under the state’s “failure to protect” law because she couldn’t stop her abusive boyfriend from beating her 4-year-old daughter. He received significantly less time behind bars for committing that violence. When my colleague Ryan Little and I conducted a groundbreaking review of Oklahoma’s court records, we identified hundreds of people like King who had been charged under the state’s law since 2009 for allegedly failing to protect their children from another adult’s harm. About 90 percent of those imprisoned under the statute were women, disproportionately Black mothers. Many of them experienced abuse from the same person, often a romantic partner, who harmed their children.

In recent weeks, Oklahoma’s legislature overwhelmingly approved the Oklahoma Survivors’ Act, which would allow courts to shorten prison sentences for people who can prove their crime stemmed from domestic violence. The legislation could help mothers like King who are convicted for “failure to protect,” as well as others who killed an abuser in self-defense, or committed a crime while attempting to escape from the abusive relationship, or followed an abuser’s order to break the law for fear of retribution. It would apply to both new and old cases, theoretically helping people with active trials or those who want to retroactively shorten their sentences.

It’s a big deal that this legislation passed with so much support: As I’ve reported before, only a few other states have laws like this, including New York. And none of those states are as conservative as Oklahoma. But the issue appears to have struck a chord on both sides of the Sooner State’s political aisle. “This may be the first time in my life I agree with someone from San Francisco,” then-Rep. Todd Russ, who is Republican and now Oklahoma’s state treasurer, wrote to me in 2022 after I emailed him from California to share our investigation. In March, the state Senate unanimously approved the Oklahoma Survivors’ Act, and in April the state House approved it with a vote of 84-3.

Despite such broad support, Republican Gov. Stitt vetoed the bill on Tuesday. He described the legislation as “bad policy,” arguing that “untold numbers of violent individuals who are incarcerated or should be incarcerated in the future will have greater opportunity to present a threat to society due to this bill’s impact.” (Our investigation found that the vast majority of women in Oklahoma convicted for failure to protect—a nonviolent crime—had no prior felony record.)

In his veto message, the governor also warned that defendants could point to abuse that happened years ago as justification for crimes they were committing today, something he described as “a bridge too far.” But that’s not how the bill would actually work. The Oklahoma Survivors’ Act applies only in cases where someone was experiencing abuse at the time they committed the offense, and only if they can prove the abuse was “a significant contributing factor” causing them to commit it. “He either has no grasp of this policy or doesn’t care enough to get involved to inform himself,” Senate Pro Tempore Greg Treat, a Republican who authored the bill, said in a statement. “Whichever it is, it’s embarrassing, especially for our state that has such a high rate of domestic violence.”

Oklahoma ranks first in the country for the most domestic violence cases per capita, according to one recent study, and many women in the state’s prisons are survivors of abuse. “Women, especially in Oklahoma, are overpunished,” Amanda Ross, whose aunt got a life sentence for killing an abuser, told the Oklahoma City-based television station KFOR-TV. Under the bill, sentences of life without the possibility of parole could be reduced to 30 years or less; sentences of 30 years or more could be reduced to 20 years or less.

The Oklahoma District Attorneys Council supports the veto, arguing the bill is too broad. But criminal justice reform advocates haven’t given up on the legislation. On Wednesday, the state Senate overrode the governor’s veto with a vote of 46-1. If the state House overrides it too, the bill could still become law. Incarcerated “survivors have been waiting and praying for the opportunity to return to their children and families,” Alexandra Bailey, a campaign strategist for the nonprofit Sentencing Project, which supported the legislation, said in a statement.

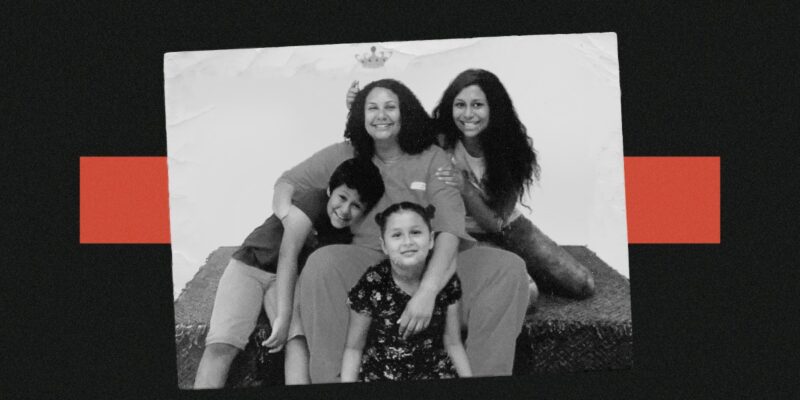

Kerry King is now nearly a decade into her 30-year sentence and has tried her best to stay in touch with her four kids, the oldest of whom was about 9 when she was convicted. She calls them as often as she can and writes them letters, and sends them socks and blankets with yarn she bought at the commissary. When I visited three of her kids in 2022, they were confused and devastated about why she was still locked up. “Like, I kind of know why she’s in jail, but I know she’s not supposed to be there,” 11-year-old Lilah said, holding back tears.

“I just really miss her,” she said. “You can’t really make memories on a phone.” To learn more about King’s case and the incarceration of other survivors in Oklahoma, read our investigation and watch the documentary I helped make with filmmaker Mark Helenowski below.