As the battle over the border rages in Congress, many Republicans are pushing to advance a bill that would revive one of the Trump era’s harshest policies: deporting family members in the US who step forward to take in unaccompanied migrant children.

It’s one of the many hardline provisions in HR 2, a sweeping border security plan that GOP leaders say is necessary to clamp down on the number of migrants arriving in the country. That bill, which passed in the House last year, is waiting in the wings as lawmakers fight over the possibility of new immigration crackdowns. The GOP legislation contains a laundry list of rules that would expand deportations, make it harder to claim asylum, and whittle down the government’s power to grant humanitarian parole. But immigration advocates are also sounding the alarm over a lesser-known provision, which instructs the Department of Health and Human Services—an agency tasked with placing migrant kids with trusted sponsors in the US—to hand over those sponsors’ names to immigration enforcement officials.

According to lawyers and activists who previously saw this collaboration take place under President Donald Trump, the past iteration of the program left devastating impacts on family members who were arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement after trying to reunite with their children. The risk of deportation, they say, terrified potential sponsors and discouraged them from coming forward, prolonging the time that kids needed to stay in detention centers.

The policy was “using children as bait in order to go after undocumented families,” says Azadeh Erfani, a senior policy analyst with the legal nonprofit National Immigrant Justice Center. It’d be “a huge setback” if Congress now codified into law “a provision that would treat children with such cruelty.”

When Border Patrol encounters an unaccompanied child or teen, the agency is supposed to move them into the custody of HHS’s Office of Refugee Resettlement, which was specifically tapped to care for minors arriving in the country alone. The office places the child in a temporary shelter before releasing them to a trusted adult in the US, usually a family member, with whom they can wait out their immigration cases in a safe environment. Most people who come forward to sponsor a child—a dad, a grandma, a family friend—are undocumented. But HHS, which is not a law enforcement agency, regularly places kids with sponsors who lack legal immigration status. “Their job is not immigration enforcement,” says Jennifer Podkul, vice president of policy and advocacy with the nonprofit Kids In Need of Defense. “Their job is child protection.”

Those lines were blurred in 2018, when, under Trump’s infamous “zero tolerance” strategy, the Department of Homeland Security inked a new information-sharing agreement with HHS. Suddenly, HHS was required to give immigration authorities the names, addresses, and fingerprints of anyone who came forward to take in an unaccompanied child. Within a year, said then-ICE Acting Director Matthew Albence in a congressional hearing, immigration enforcement agents had used this intel to round up over 300 potential sponsors. Most of them had no criminal records and were arrested solely because they were suspected of being in the country illegally.

Two months after Biden took office, his administration rolled back the policy. The setup had “undermined the interests of children” and “had a chilling effect on potential sponsors,” DHS and HHS announced in March 2021 in a joint statement.

Now, many say that the Republicans’ border bill could bring back the program—and exacerbate its harms. “HR 2 goes one step farther,” says Melissa Adamson, an immigration attorney with the National Center for Youth Law. Unlike the Trump-era agreement, HR 2 explicitly tells HHS to report a sponsor’s immigration status to Homeland Security. If they’re undocumented, the authorities would have 30 days to begin the process of deporting them.

If HR 2 were implemented, “family members would not come forward” and “children’s length of time in detention would likely skyrocket,” Adamson says. “It would be a wholly preventable crisis.”

For many immigration advocates, this potential crisis is reminiscent of what they saw the first time around. They recall how relatives were often scared that engaging with HHS would result in ICE, which is part of DHS, showing up at their doorstep, leaving kids without other options. At that point, “you’re looking at a situation where there just may not be someone to sponsor the child,” says Mary Miller Flowers, the policy and legislative affairs director for the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights. “You may take that child’s whole network away from them.”

As a result, once the Trump policy took effect, kids had to wait for much longer stretches of time as case managers scrambled to track down a more distant relative or family friend. “It became more difficult to identify sponsors willing to accept children,” explained the HHS Office of Inspector General. In the months after the agencies’ cooperation started, the average time children spent in HHS custody ballooned—from 58 days to about three months.

But each day, unaccompanied kids continued to arrive at the border. This created a huge backlog in HHS shelters, which were quickly running out of bed space. Newer arrivals couldn’t move out of Border Patrol detention centers—austere facilities meant for the short-term holding of adults. Federal law generally requires that minors without a parent or guardian be transferred out of those centers within 72 hours, but many were staying for weeks. Unlike HHS shelters, which are designed to house children, Border Patrol jails often lacked basic supplies like toothbrushes or soap and were so freezing that people called them “iceboxes.” These facilities are “dramatically ill-equipped to care for human beings, let alone children, in a long-term way,” says Erfani. Even after Biden ended the Trump-era policy, she notes, an 8-year-old girl died in Border Patrol custody last summer after agents ignored her parents’ pleas for medical care.

The Trump administration argued that it was looking out for the safety of child migrants. It said that Homeland Security officials needed to vet sponsors to make sure kids weren’t being released to harmful settings. “No one who values child welfare and safety,” then-White House spokesman Hogan Gidley told the Washington Post in 2019, “would argue smuggled, exploited and unaccompanied children at the southern border should be handed over to illegal alien ‘sponsors’ without reliable identity confirmation and background checks.”

But many advocates say that ICE’s renewed involvement would have nothing to do with child welfare. “It’s purely punitive,” says Melanie Nezer, vice president of advocacy with the Women’s Refugee Commission. HHS’s refugee office was specifically asked to care for unaccompanied kids, she pointed out, so that their wellbeing would be overseen by an agency without a law enforcement mandate. In recent months, HHS has come under fire for not properly vetting sponsors and often releasing children to exploitative labor settings. But adding immigration authorities to the mix, Nezer argues, would only make things worse. A desperate parent might try to find someone—anyone—who has legal status to sponsor a child, even if that’s a distant relative or a stranger.

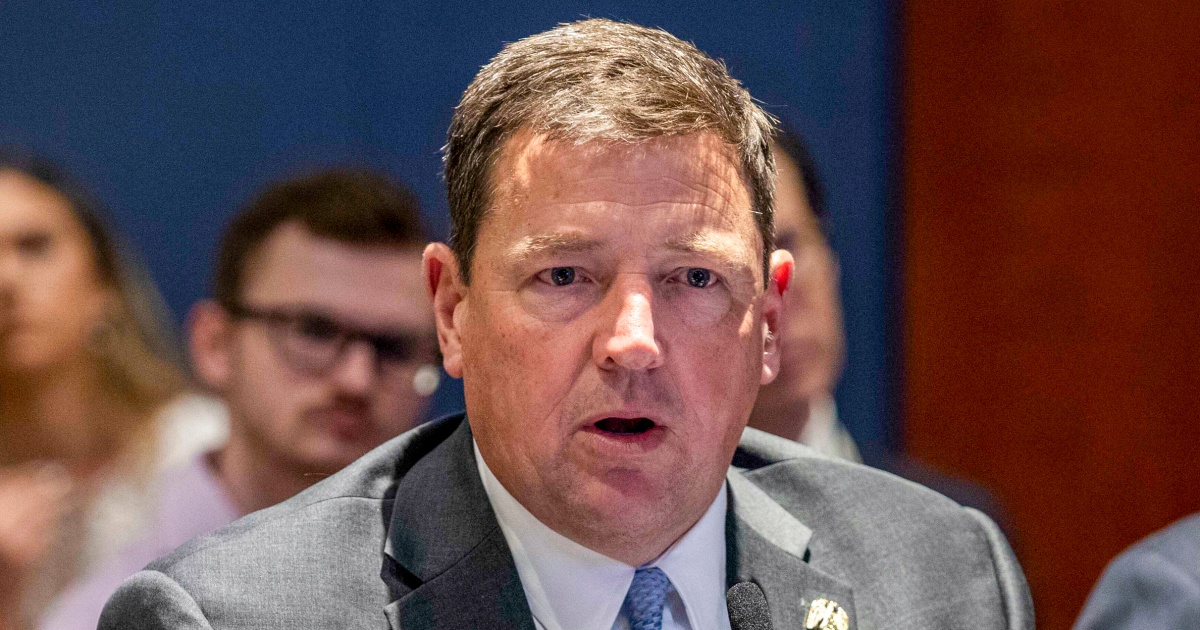

As lawmakers strain to compromise on new immigration limits, HR 2 is in the spotlight again. Earlier this month, after a botched attempt to reach an agreement on border security in the Senate, House GOP leaders Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.), Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.), Steve Scalise (R-La.), and Tom Emmer (R-Minn.) issued a statement once again pressing the Senate to vote on HR 2. That’s unlikely to happen anytime soon in the Democratic-controlled upper chamber. But things could change if Republicans win control of the Senate in November.

Republicans “are socializing these ideas through HR 2,” says Flowers of the Young Center. Just putting it on the table “makes it look like these kinds of extremist things” are “somehow part of our mainstream conversation about how to manage immigration in this country.”