Back in 2011, the New Yorker published a Charles Barsotti cartoon that I, as a scholar of wealth power in liberal democracies, found brilliant: A rotund executive in a business suit is saying to his C-suite pal: “‘Oligarch’—terrible word, we’ll need a new one.”

Barsotti’s caption alluded to the post-Great Recession battle—exemplified by Occupy Wall Street protests and rising references to the 1 percent vs. the 99 percent—over the way we talk about the powerful rich. More than 100 years earlier, at the tail end of the 19th century, the wealthiest Americans—Rockefeller, Carnegie, Vanderbilt, etc.—were very unhappy with being called “robber barons,” a name first given to medieval aristocrats who amassed fortunes through odious and unethical practices. They soon launched a campaign to replace it with a more valiant expression, like “captains of industry.”

The term “capitalist” itself has long had a mixed meaning. Among conservatives, it means entrepreneur and innovator. On the left it connotes greedy exploiter, and perhaps even planet destroyer. “Plutocrat” has gone in and out of fashion in the United States, but never really gained traction.

Since the end of the 20th century, the term “job creators” has been in wide circulation, especially from Republicans after Occupy. Mitt Romney, during his unsuccessful 2012 bid to unseat President Barack Obama, told the US Chamber of Commerce that Obama “has decided to attack success. It’s no wonder so many of his own supporters are calling on him to stop this war on job creators.” (Romney was later famously caught on camera at a private fundraiser suggesting, in so many words, that 47 percent of Americans were “takers” not “makers.”) This sort of language, later championed by former Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan, suggested that the ultra-rich were merely America’s humble servants, without whom we would all be jobless and perish.

More recently, “oligarch” is making a comeback, and ruffling pampered feathers along the way. Starbucks founder and former CEO Howard Schultz, while exploring a 2020 presidential bid, even bristled at being branded a “billionaire” by the media, which to him felt like a dig—“people of wealth” and “people of means” were his preferred expressions. But the word “oligarch” precedes the existence of billionaires. Ever since Aristotle wrote about oligarchs 2,300 years ago in his book Politics, the term has always referred to those empowered politically by massive wealth.

Over the centuries, oligarchs have either ruled directly or exerted their societal influence through others. As I wrote in a 2017 academic paper, “For thousands of years, being rich involved being armed, engaging in violence and coercion, extracting resources from broad territories, while also holding positions of direct rule.” Today, in republics such as ours, oligarchs exercise their wealth power to influence candidates, elected officials, charitable institutions, and alas, susceptible Supreme Court justices—to achieve similar outcomes.

Like the rest of us, oligarchs disagree on many issues. But what unites them is a shared focus on wealth defense—which in the modern era means fighting against redistribution to the non-rich. Starting in the 1950s, when the highest income tax bracket topped 90 percent, an entire Wealth Defense Industry, a concept I introduced in my 2011 book, Oligarchy, arose solely for this purpose.

The term “oligarch” differs from “robber baron” in that it was never about getting rich through corruption. How oligarchs make their fortunes was never actually part of the definition. The only thing that matters is the enormous power the riches confer. The label describes a power position, not an ethical one.

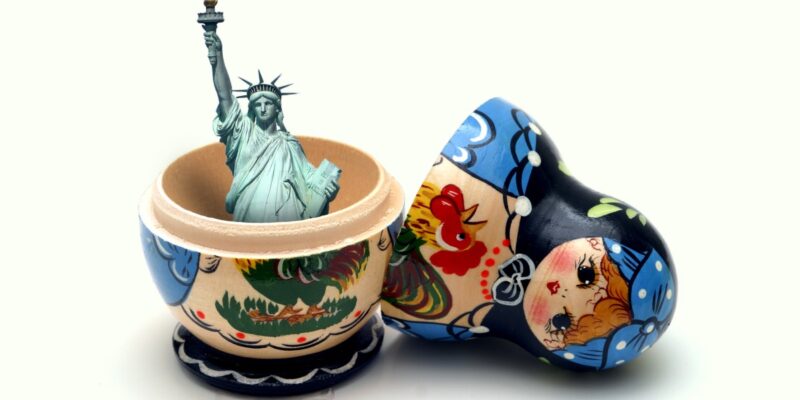

In deference to American oligarchs, the norm of late is to limit the term to the criminally rich. Some years ago, a student in a seminar I teach on oligarchs and elites declared on the first day of class that “Russia has oligarchs; the US has rich people.” America’s oligarchs would have suppressed a smile.

In fact, there is no special species of “Russian oligarchs.” There are oligarchs all over the world, some of whom happen to be Russian. As suggested by the charts that accompany Tim Murphy’s Mother Jones essay, “The Rise of American Oligarchy,” far more are homegrown, and these American billionaires have amassed even more wealth and power than their peers elsewhere.

America’s oligarchs nowadays are more comfortable being called “mega-donors,” a term commonly used by media outlets of all stripes. The term is interesting in that it acknowledges the political role of the rich, but it casts their attempts to dominate and control our institutions as a donation, rather than as an expression of democracy-distorting power. (For the record, the only true US mega-donors are people like Marc Satalof, the 76-year-old recently in the news for donating his 280th pint of blood—35 gallons over a half-century.)

When it comes to politics, oligarchs are the opposite of donors. For millennia, they have deployed their wealth power to advance their interests. Whether operating in liberal democracies or dictatorships, they exhibit only one consistent pattern: defense of their riches.

The American experience proves this beyond any doubt. A 2020 study on the explosion of US inequality by the Rand Corporation—a conservative think tank—estimates that, since 1975, some $50 trillion in wealth has been shunted from US workers earning below the 90th percentile into the hands of the top-earning 1 percent. Had the inequality levels of the mid 1970s held constant, the study showed, the bottom 90 percent would today be bringing in at least $2.5 trillion more per year—which translates into a median family income 67 percent higher than the current figure.

Mega-donors or oligarchs? You decide.

To read more about the distorting effects of oligarchy on US culture and politics, see Mother Jones’ special investigation, American Oligarchy.