When the US targeted Russia’s oligarchs after the invasion of Ukraine, the trail of assets kept leading to our own backyard. Not only had our nation become a haven for shady foreign money, but we were also incubating a familiar class of yacht-owning, industry-dominating, resource-extracting billionaires. In the January + February 2024 issue of our magazine, we investigate the rise of American Oligarchy—and what it means for the rest of us. You can read all the pieces here.

In a December 2021 blog post, MacKenzie Scott expressed her surprise at the “inclusive and beautiful” definitions of philanthropy, such as “love of humankind,” that she’d discovered in the dictionary. Scott, who has given away more than $14 billion since divorcing Amazon founder Jeff Bezos in 2019—and who has pledged to “keep at it until the safe is empty”—wrote that she’d never identified with the expression in such a positive way: “What had happened? Somewhere along the line, this big, lovely word had shriveled to describing the humanitarian impulses of less than 1 percent of the world’s population.”

Perhaps we simply forgot that philanthropy in America has never been much more than a plutocratic flex.

In Prometheus Bound, the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus coined the adjective philanthropos—from phil (loving) and anthropo (human)—to describe the fallen Titan’s fondness for the bumbling protohumans he’d fashioned out of clay. Zeus wanted the pathetic beings destroyed. Instead, Prometheus gave them the gifts of “blind hope” and fire (proprietary Olympian tech), which brought about human agency, culture, and civilization.

Gifts bestowed by godly figures, according to their whims, for the betterment of humankind as they interpret it. Sound familiar? Indeed, our laudatory view of philanthropy is a recent historical development, one that emerged before the wealth of the richest 0.001 percent went quite so parabolic.

As during America’s first Gilded Age, the desire of the world’s wealthiest people to legitimize their ever-growing hoards has spawned a spate of conspicuous giving, explains Stanford political scientist Rob Reich, author of the 2018 book Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy and How It Can Do Better. In this new era of market fundamentalism, he told me in an interview, “that meant putting Bill Gates and Bono on the cover of Time magazine as the person of the year—and thinking about social entrepreneurs as the way to improve the world.”

The Gilded Age philanthropists faced a far more skeptical public. Consider the saga of Standard Oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, not only the richest man of his time but the richest who has ever lived—which became a problem, even for him. “Your fortune is rolling up, rolling up like an avalanche!” Frederick T. Gates, his trusted adviser, warned in a 1905 letter. “You must keep up with it! You must distribute it faster than it grows! If you do not, it will crush you, and your children, and your children’s children!”

Rockefeller took the advice to heart. A few years later, as Reich recounts in his book, he approached Congress seeking a charter—a federal stamp of approval—for one of the nation’s earliest, and certainly largest, general-purpose private charitable foundations.

Foundations were having a moment thanks to Rockefeller’s contemporary, Andrew Carnegie, whose 1889 essay, “The Gospel of Wealth,” remains modern philanthropy’s most cherished founding document. The essay begins with a grandiose defense of wealth inequality—which Carnegie casts as the inevitable byproduct of supremely talented men creating the economic tides that lift all boats. Yet, he notes, “ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relationship” if these captains of industry would redirect their great wealth and abilities to helping the less fortunate help themselves.

In Carnegie’s view, large inheritances are a recipe for family destruction, and the millionaire who bequeaths his fortune for public benefit only upon death “dies disgraced.” Public officials, he suggests, quoting Shakespeare, should thus ensure that “at least” half of such fortunes go “to the privy coffer of the state”—a 50 percent estate tax.

Carnegie built universities, museums, and thousands of libraries—the foundation for America’s public library system. Yet he vehemently opposed “indiscriminate charity,” lest it be “spent as to encourage the slothful, the drunken, the unworthy.” His approach, modern philanthropy’s blueprint, demanded that wealth creators pick the winners and steer their progress.

Carnegie is more revered than reviled these days, but he faced tough critics back then. One prominent minister praised Carnegie personally but deemed his rarefied ilk a “social monstrosity” and a “grave political peril.” Another notable scholar accused him of advocating “a vast system of patronage.”

The public saw Carnegie as a ruthless robber baron. A few years after “Gospel” appeared, workers at his steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, asked for a pay increase and received a retaliatory pay cut instead. Carnegie’s plant manager, Henry Frick, locked out the protesting workers and brought in thousands of strikebreakers and hundreds of armed Pinkerton agents, resulting in violence that left at least 10 people dead. The National Guard was summoned, and after the union was crushed, Carnegie slashed wages and instituted 12-hour workdays.

So perhaps it’s no surprise that Rockefeller’s foundation proposal didn’t get the reception he’d hoped for in DC. Reich writes that President William Taft attacked his proposal as “a bill to incorporate Mr. Rockefeller,” and Taft’s attorney general cautioned that allowing such power to “be invested in and exercised by a small body of men…might be in the highest degree corrupt in its influence.” Unitarian minister John Haynes Holmes, a co-founder of the ACLU and the NAACP, testified that he presumed Rockefeller had good motives, but “it seems to me this foundation, the very character, must be repugnant to the whole idea of a democratic society.”

To appease his critics, Rockefeller offered to cap the foundation’s assets at $100 million, subject it to public oversight, and spend it into oblivion within 50 years. That won over the House, but the Senate balked, so Rockefeller turned to the New York Legislature, which granted his charter in 1913, minus those pesky provisions. That same year, Congress passed the latest of a series of laws that created the modern tax system, exempting “any corporation or association organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, or educational purposes” from taxation.

In short, federal lawmakers blew their first and best chance to hold Big Philanthropy to account. We are now living with the result: a sprawling network consisting of some 1.8 million taxpayer-subsidized charitable entities, including more than 103,000 private foundations that can exist in perpetuity, unbeholden to the public, while amassing unlimited wealth.

Foundations, Reich notes, needn’t have a website, a physical office, or even a phone number, nor must they reveal their donors or giving strategies. They need only file an informational IRS return, adhere to basic rules against “self-dealing” (they are seldom audited), and expend a paltry 5 percent of their assets annually—including overhead—for charitable purposes. At the end of 2019, the IRS estimates, private foundations were sitting atop more than $1.1 trillion in assets.

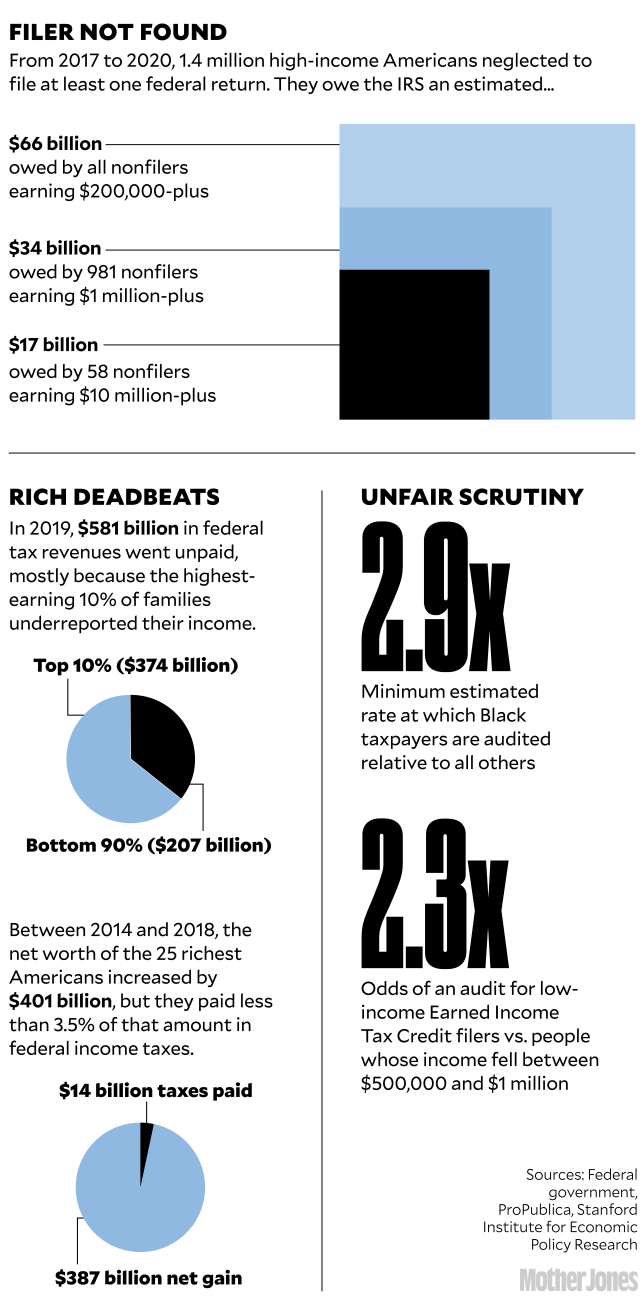

Whether America’s ultrarich bankroll noble causes or reprehensible ones, all major philanthropists have two things in common. First, their giving buys them perks, unrivaled access, and significant sway in the academic, business, government, and nonprofit realms. Second, they enjoy huge tax breaks. That is, you and I subsidize their giving without getting any say in how that money is spent.

And it’s a lot of money. The charitable tax deduction alone costs the federal government $56 billion a year in lost revenue, and states and localities are denied tens of billions more—money that cannot be used for parks and public safety, climate resilience projects, anti-poverty programs, or even just balancing budgets.

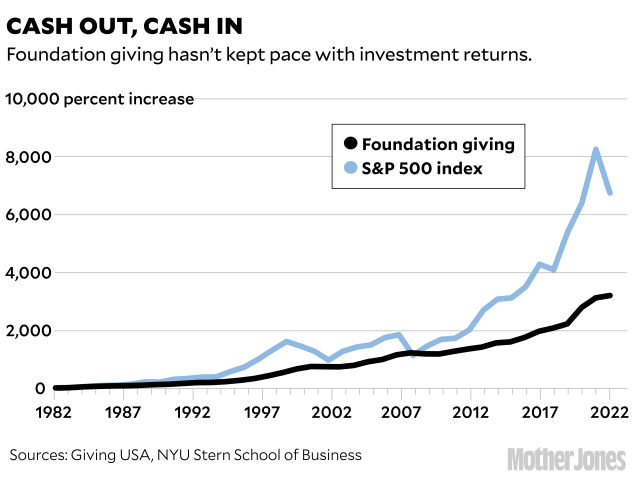

Foundations are wealth hoarders. They typically give only a tad more than the bare minimum. Over the past five years, according to the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), median payout rates for foundations worth $1 billion or more ranged from 4.6 and 5.4 percent. And the charity trickling out of the foundations is often dwarfed by gains flowing in.

At the end of 2019, per the IRS, there were 1,328 grant-making foundations valued at $100 million or more. These entities doled out $48.5 billion to various causes that year—about 7 percent of their combined $703 billion in year-end assets. Meanwhile, they pocketed investment income (dividends, interest, etc.) of about $44 billion and tax-deductible gifts of $38.5 billion, paying well under $1 billion in taxes. This left, after expenses, “excess revenues” of about $18 billion, and tens of billions more in unrealized investment gains.

Affluent families also enjoy tax breaks on cash or stock they contribute to a donor-advised fund, which is basically a parking spot for future giving. DAFs, which have even less transparency than foundations and no minimum payout, have more than doubled in number and size since 2017, to nearly 2 million individual accounts with $229 billion in assets in 2022. Charitable disbursements from DAFs have more than doubled, too, and average payout rates beat those of foundations. But as with the foundations, more assets flow in than out each year, leaving behind an ever-growing mountain of publicly subsidized cash.

The exemptions in our tax code acknowledge the value of engaged citizens supporting bold ideas and laudable causes, and fair enough. But who gets those breaks, and how laudable, really, are the causes? If your household earns $90,000 per year and, like more than 85 percent of federal tax filers, you take the standard deduction on your 1040, that means your $1,000 gift to a food bank costs you $1,000 out of pocket. If Oracle’s Larry Ellison makes the same gift, with his 37 percent tax bracket and itemized deductions, he pays only $630. Little surprise that the share of US households giving to charity has been in freefall since the Great Recession, while giving by private foundations has more than doubled.

Not to say philanthropy is bad. Just broken. Carnegie’s notion that it would narrow the chasm between wealthy capitalists and their factory workers certainly hasn’t come to pass. You won’t encounter any such workers at red-carpet events like the Met Gala, “which is in principle a charitable fundraiser but more than anything else a status-signaling occasion that being philanthropic is the price of admission to,” Reich told me.

In a recent Bank of America survey, “affluent” adults (average wealth: $31 million) distributed 39 percent of their charitable dollars to religious institutions and 24 percent to higher education, but only 10 percent to “basic needs” giving and less than 1 percent to racial justice causes. “Philanthropy is not often a friend of equality, can be indifferent to equality, and can even be a cause of inequality,” Reich writes.

So, what are we subsidizing? Sometimes it’s a billionaire’s ego. Jeff Bezos has given at least $42 million to a tax-exempt foundation to construct, on his own property in West Texas, an enormous clock designed to keep time for 10,000 years. “In the year 4000,” Bezos told Wired, “you’ll go see this clock and you’ll wonder, Why on Earth did they build this?” (Good question.)

Sometimes it’s the wealthiest college on the planet. Last April, hedge fund titan Ken Griffin donated $300 million to Harvard, his alma mater. Harvard’s $51 billion endowment and Griffin’s net worth (~$36 billion as of mid-December) both exceed the GDPs of most nations. If Griffin uses his $300 million gift to offset his dividend income for tax purposes, Harvard is effectively getting a $189 million gift from him and a $111 million gift from the federal government. But only Griffin gets the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences renamed in his honor.

This is par for the course. In 2016, for Stanford’s Social Innovation Review, a team of philanthropy professionals examined where the “big bets”—donations of $10 million or more—wound up. While 60 percent of the major philanthropists studied had publicly cited a “powerful social change” as their top priority, all but 20 percent of the big bets they made between 2000 and 2012 (excluding the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) went to universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions that were “often already richly funded, with ample capacity to continue securing major gifts.”

Some of those philanthropists had signed the Giving Pledge. In 2010, the Gateses, their pal Warren Buffett, and 37 other billionaires promised to dedicate a majority of their wealth to charitable ventures, whether in life or death. As of December 2023, 242 ultrawealthy citizens or couples—from the Indian metal baron Anil Agarwal to Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg—from 29 countries had signed up.

Sounds generous, but several caveats are in order. The pledge is a “moral commitment…not a legal contract,” so signatories cannot be held to it, and less than 8 percent of the world’s 3,194 billionaires are “members.” The pledge also can be viewed as a consolidation of plutocratic power, as seen when the pledgers huddle at exclusive annual gatherings to compare notes on how they will change the world.

Finally, a “majority” of one’s fortune is half plus a penny. Most of these people could give away half their assets and not even feel the difference. In fact, after adjusting for inflation, at least 60 percent of the 75 living American moguls who have been on the pledge list for a decade or more have as much wealth today as when they signed up—18 have seen their net worth at least triple during that time.

Some signers say they’ll give more. Ellison, whose net worth in mid-December was about $130 billion, said he’d give away “at least 95 percent.” Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan have pledged to dole out 99 percent of their Facebook stake during their lifetimes. But Ellison has barely scratched the surface, according to IPS, and Zuck’s wealth, as of mid-December, had ballooned to more than 21 times what it was when he joined the Giving Pledge in 2010.

Zuck has sizable stakes in other companies as well, and at the rate wealth compounds, he and Chan will likely remain billionaires for life. They also own hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of real estate, including multilot compounds in Palo Alto and at Lake Tahoe, and 1,500 acres in Kauai. (Ellison owns almost the entire island of Lanai.) In 2008, before Facebook went public and when Zuckerberg was just 24 years old, he put 3.4 million shares into a type of trust routinely used by the world’s richest families to transfer gigantic fortunes to their heirs without paying a dime in gift or estate tax.

Billionaires’ Giving Pledge: Part Tax Strategy, Part PR Stunt

Since 2010, some 241 of the world’s richest people and couples have committed to giving away at least half of their fortunes. The Giving Pledge starts with a simple premise: Collective giving, in the words of co-founder Bill Gates, can “help the world become a better place.” You be the judge. Read the full list here.

Philanthropic giving also serves as what Reich calls “a legitimation project” or, put more bluntly, “a reputation-laundering exercise to construct an aura of altruistic do-gooding and distracting people from attending to the source of the moneymaking.”

In his 2018 book, Winners Take All, journalist Anand Giridharadas takes aim at the Sackler clan, whose reckless, ruthless peddling of opioids contributed to the overdose deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans. The Sacklers greased their ignoble ascent and cushioned their fall from grace with more than $60 million in tax-deductible gifts to universities, and millions more to cultural institutions, including the Louvre, the Met, and the Guggenheim, some of which were later compelled to strip the Sackler name off their buildings.

Give abundantly, Giridharadas wrote of the philanthropist’s ethos, “and expect in return that questions will not be asked about the money’s origins and the system that let it be made.”

Giving back also can do wonders to repair a reputation—temporarily anyway. After stepping down as Microsoft CEO in 2000, Bill Gates set about remaking his image—from “tyrannical technocrat” to “huggable billionaire techno-philanthropist,” as one Bloomberg writer put it. And although the Gateses have funded some impressive global public health initiatives, they’ve taken flak for blocking poor countries’ access to Covid vaccines and for imposing their will on America’s public education system with little to show for it.

After plea-bargaining his way out of his first indictment, sex predator Jeffrey Epstein used philanthropy to ingratiate himself with celebrity scientists. Officials at elite colleges (Harvard, MIT) and financial institutions (J.P. Morgan, Deutsche Bank), as well as powerful men like Gates (whose association with Epstein may have expedited his divorce), looked the other way.

“Good billionaire” philanthropist Warren Buffett has quietly arranged his financial affairs to avoid taxes almost entirely. He is also among the nation’s most prolific fossil fuel investors, adding $3.3 billion in 2023 to Berkshire Hathaway’s $40 billion-plus portfolio of polluters. Son Howard Buffett has spent more than $200 million from his own foundation to impose his values on the small city of Decatur, Illinois, and micromanage its local affairs. George Soros spends billions on liberal political causes with the aim of defeating authoritarianism. Love or hate him, he wields astounding plutocratic power. And recent shake-ups at his foundation abruptly cut off scores of dependent nonprofits—yet another way philanthropy can be destabilizing.

Sometimes it is downright misanthropic. New Yorker reporter Jane Mayer—who has detailed how conservative dynasties such as the Kochs, the Scaifes, and the DeVoses have “weaponized” philanthropy to serve ideological and business interests—more recently trained her sights on the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, “an extraordinary force in persuading mainstream Republicans to support radical challenges to election rules.” With $1.2 billion in assets in 2021, the Bradley Foundation “funds a network of groups that have been stoking fear about election fraud, in some cases for years,” Mayer wrote.

Which brings us to another big asterisk: the wildly broad definition of what constitutes a tax-exempt charity. On the one hand, we have nonprofits “fostering appreciation” for camellias and “promoting the medium of American mime.” On the other, we have the Federalist Society, a dark-money group co-chaired by Leonard Leo, whose starring role in the Supreme Court ethics scandals “reeks of corruption,” as Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) put it.

Ditto the American Legislative Exchange Council, the secretive cabal that translates the will of wealthy donors, corporate lobbyists, and right-wing politicians into model state laws. Examples include stand-your-ground legislation, laws that bar cities from restricting gun sales, and “anti-ESG” laws meant to punish institutions that divest from fossil fuels or to forbid state pension funds from factoring environmental and social factors into their investment choices.

The philanthropic world, spurred by rising criticism and the dire needs exposed by the pandemic, has gone through a period of soul-searching. More foundations, though still a small minority, have imposed limits on their lifetimes. Attorney Harvey Dale—who, as president and CEO of the Atlantic Foundation, helped the recently departed billionaire Chuck Feeney stealthily give away his entire fortune—told me he was advising several other “very wealthy” people who plan to do the same.

Before the pandemic, Ford Foundation President Darren Walker, who then oversaw a $13 billion endowment, began challenging his peers to reconsider their giving strategies and to think about how their profit-driven investments might be counterproductive to their missions. “How does our work,” Walker wrote, “reinforce structural inequality in our society? Why are we still necessary, and what can we do to build a world where we no longer are as necessary?”

But Big Philanthropy is too self-interested to reform itself out of existence, and billionaire wealth and foundation endowments will only continue to grow—the Ford Foundation’s is up to $16 billion now.

Enforcing existing laws would be one positive step; Sens. Whitehouse and Elizabeth Warren have urged the IRS to crack down on political nonprofits and foundations that abuse their tax-exempt status. Lawmakers also could kill tax-avoidance trusts, place limits on foundations’ tax-exempt lifetimes, and require foundations and DAFs to make annual payouts that match or exceed their marketplace gains.

At the very least, they could close the “undesirable” loophole, in Dale’s words, that allows foundations to pass off donations to their creators’ DAFs as charitable giving to be included in the mandatory 5 percent payout.

Reich proposes that Congress do away with the charitable tax deduction entirely and replace it with a $1,000 credit available to all. Philanthropists would cry foul, claiming such a move would decimate contributions, but Reich is unconvinced. From the 1940s through the mid-1960s, the top federal income tax rates exceeded 80 percent—a more powerful incentive for big earners to donate than exists today—but giving as a share of GDP has stayed “more or less constant” over the decades, Reich notes, at about 2 percent.

Without the charitable deduction, parents in wealth havens like Woodside, California, will still donate millions each year to local education foundations to ensure their public schools are indistinguishable from private ones—a perfect example of how well-intentioned giving can perpetuate inequality. Harvard will still get its buildings and Bezos his groovy clock. Maybe the Bradleys will even be able to keep interfering with our elections. But at least the rest of us won’t have to pay for it.