Editor’s note: The below article first appeared in David Corn’s newsletter, Our Land. The newsletter comes out twice a week (most of the time) and provides behind-the-scenes stories and articles about politics, media, and culture. Subscribing costs just $5 a month—but you can sign up for a free 30-day trial of Our Land here.

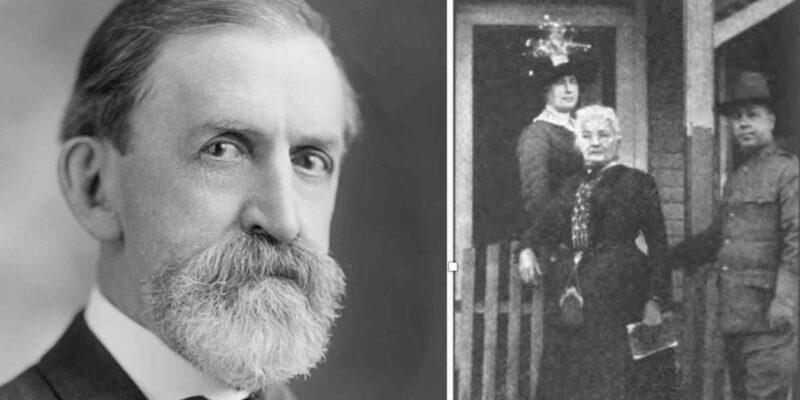

I spend a fair bit of time in West Virginia. I have friends who co-own what used to be a fishing and hunting lodge in the beautiful and rugged mountains of the Monongahela National Forest far away from most everything, and for years my family and I have enjoyed sojourns there. On a recent visit, our host showed me a biography of his great-grandfather, John Kern, a Democratic senator from Indiana, the first Senate majority leader, and the Democratic vice presidential nominee in 1908. (He was on the ticket with William Jennings Bryan that lost to William Howard Taft.) I started flipping through the volume, The Life of John Worth Kern, published in 1918 and written by Claude Bowers, a newspaper columnist who produced a string of bestselling books about American history, and I came across an entire chapter about Mother Jones (the person) and how Kern teamed up with her to beat back a big-money lobbying campaign in the US Senate. It’s a story that resonates today.

Naturally, I’m familiar with the general arc of Mother Jones’ life. Mary Harris Jones was an Irish immigrant whose birth date was uncertain. She was baptized in 1837. Her family, due to the Great Famine, moved to Toronto when she was about 10, and as a young woman she immigrated to Michigan to become a teacher at a convent. She soon married an organizer for the National Union of Iron Moulders. Her husband and four children died of yellow fever in 1867, and she opened a dress shop in Chicago. After her business was destroyed in the Chicago Fire of 1871, she became a labor activist, most noteworthy for her stint as an organizer for the United Mine Workers, during which she adopted her nom de political guerre.

Yet I didn’t know that Jones successfully lobbied the Senate to beat back an effort to protect feudalism in West Virginia.

At the heart of this tale are the infamous labor battles in the coal mining regions of the Mountain State. As Bowers describes it, in the towns of Paint Creek and Cabin Creek, coal mining firms had established a “form of peonage.” Miners were forced to live in high-rent housing owned by the companies and to purchase food at exorbitant prices from company stores, while receiving meager pay. “These men were slaves,” he noted. Worse, they lived under the heel of “mine guards”—militias of gunmen that were “composed largely of the scourings of the slums of the cities” and that had no “legal status.” A key goal of the guards: to keep out organizers from the United Mine Workers and prevent journalists from nosing about. “Popular government,” he wrote, “had broken down and had been displaced by the feudalism of the coal barons and their allies.”

Cabin Creek was fully under the thumb of the coal companies, but Paint Creek workers were organized. And in 1912, Big Coal decided to break the union there. The area was “invaded by the gun-men.” They terrorized the miners and their families, breaking into their homes, harassing their families, and stealing their food. They even “let loose the flood gates of profanity and vulgarity in the presence of women and babes.” One pregnant woman who was kicked and roughed up by the goons lost her child. Some miners and their families were driven out of their homes into a tent city. Newspapers in Charleston, the state capital, sided with Big Coal and claimed anarchistic miners were attacking “the representatives of law and order.”

Enter Mother Jones. She arrived in Charleston on July 6, 1912, about 80 years old. Already well known as a labor organizer and strategist, she led a march of thousands of miners to the statehouse. She demanded the governor order the removal of the gunmen. He did not do so, and the miners “proceeded to arm themselves,” according to Bowers. This led to a “pitched battle” between the miners and the guards that “left the guards in danger of annihilation.” The governor sent in a militia to try to disarm both sides. Meanwhile, Jones headed to Cabin Creek and organized workers there for the UMW. When company guards tried to prevent one of their meetings, they were assaulted by 500 armed miners. “West Virginia was in a state of civil war,” Bowers observed. The governor declared martial law.

In early 1913, while Jones was on a speaking tour seeking support for the miners, the violence intensified. An armored train came through a mining camp and fired on the workers, killing at least one. State troops arrested a large group of miners. Back on the scene, Jones encouraged the workers “from taking extreme measures” and organized a committee to call on the governor and request the release of the detained miners.

When she and her allies arrived in Charleston, she was arrested by local police and then conveyed 22 miles into the martial law zone, turned over to military authorities, and placed under house arrest in “the house of a poor miner where the only furniture in the room was a small lounge on which she slept, a small table and two rocking chairs, with no wash bowl.” She was guarded by militiamen for two months, while awaiting trial in a military court for the murder of a coal company bookkeeper who had been killed during one of the confrontations between miners and the guards.

Up to now, Bowers pointed out, there had been scant press coverage of the conflict in West Virginia. But when the Washington Post reported “in less than a dozen lines” that Jones was to be tried by a military court, “the system made a fatal blunder.” Sen. Kern spotted that item in the paper and was amazed that it provided “so little information.” He began to ponder what should be done.

Soon after, a fuller account of the travails of Jones and the miners appeared in Collier’s Weekly. Cora Baggerly Older, the wife of Fremont Older, the editor of the San Francisco Bulletin, had traveled to West Virginia to cover the murder conspiracy trial of Jones and 48 men in the military court. She found Paint Creek under full military occupation. When she tried to speak to Jones, she was arrested—and then released.

Older finally got the chance to talk with Jones, who met her “with curling tongs in hand,” as Older recounted. Older told Jones, “They say you must choose between leaving the state and going to jail.” Jones laid down her curling tongs and replied, “I choose jail now. I can raise just as much hell in jail as anywhere.” Other press accounts about the conflict and Jones’ arrest followed.

Kern decided Senate action was warranted. He introduced a resolution calling for a Senate investigation to determine if the coal companies were running a peonage system in West Virginia and whether the legal rights of the miners were being violated. The immediate rise of fierce opposition to his measure, Bowers reported, astonished the senator. One of the owners of the West Virginia mines—who happened to be a former US senator—wired his past colleagues and protested establishing an inquiry. Other fat cats contacted Kern:

Men with no apparent interests in the coal mines nor citizens of West Virginia began to wire and phone their importunities to drop the proposed investigation. Many railroad officials seemed morbidly concerned. The highest financial circles of New York City brought every possible influence to bear.

Kern did receive letters and telegrams “by the hundreds” from miners and their neighbors attesting to the horrific conditions. Older visited Kern and described her trip. UMW officials weighed in. But the the monied interests shook the senator to his core. As Bowers put it,

The climax of this campaign came when an old and valued friend in New York City connected with one of the great financial groups of that city called [Kern] on the phone in an effort to dissuade him. “I will see you in hell first,” was the reply as Kern slammed up the receiver.

The West Virginia governor attacked Kern “in the most bitter language.” Across the nation, the “conservative element” pilloried Kern as a “demagogic sensationalist in league with lawlessness.” In the Capitol, his foes decried his resolution as a deadly blow at states’ rights. This was a battle royale. Bowers noted the historic stakes (perhaps in grandiose terms): “Never before in the history of the United States Senate in a straight contest between the lowly or the workers and the great financial interests had the workers won—and the politicians were judging the future by the past.”

Back to Mother Jones. Under house arrest in West Virginia, she had no idea what was happening in Washington. Then one day, someone threw through her window a copy of the Cincinnati Post with a story on the fight over Kern’s resolution in the Senate. She smuggled out a message that was sent to Kern via telegram:

From out of my military prison walls, where I have been forced to pass my eighty-first milestone of life, I plead with you for the honor of this nation. I send you groans and tears of men, women and children as I have heard them in this state, and beg you to force that investigation. Children yet unborn will rise and bless you.

Kern got the message and released it to the press. It “flashed across the country” and Jones’ imprisonment sparked an uproar. She was released from her boarding house prison and escorted to Charleston, where she was courteously received by the governor. She then headed to Washington to assist Kern:

She trudged the interminable marble corridors of the Senate office building, informing senators individually and at length of the conditions in West Virginia. At times, the eighty-odd years bore heavily upon her and worn and weary she would return to Kern’s office, sink exhausted into a chair for a rest of a few minutes—then on her way again.

Kern disseminated scores of letters and telegrams from the miners, including those held in jail, stripped of their constitutional rights, denied a jury trial, and facing court martials. In a passionate speech, Kern noted “the fire of Socialism” was being fueled by the conditions in West Virginia and the “lawless action there.” He warned, “Socialism grows and will grow in exact proportion as wrongdoing is countenanced.” He stated that should the “American Republic” face a military threat from overseas, “we will need those million of men.” He asked, “Do you make good citizens of men by denying them their rights? Do you command the respect and the patriotism of the toilers of this land by turning them away when they come into this great tribunal and simply ask that the light be turned on?”

Other prominent senators–including Elihu Root (R-N.Y.) and William Borah (R-Idaho)—backed the Kern resolution. Root contended it was vital to the preservation of American democracy. After weeks of tussling, the measure passed in the Senate on a voice vote. The Senate education and labor committee would initiate an inquiry. In his book, Bowers declared, “Thus for the first time in the history of the senate in a fight involving a contest between capital and labor the workers won.”

The subsequent investigation, he wrote, “was a vindication—and a triumph for the miners.”

The committee met in Charleston in July and continued its work in Washington in September and October. Soon it issued its findings that included the conclusion that the miners were induced through “misinformation and misrepresentations” to accept employment in the coal mines and that “hardships in this respect were disclosed.” Bottom line: The coal profiteers had bamboozled the workers. Moreover, the committee, according to Bowers, affirmed “the all important charge that the constitution had been set aside, martial law established, men arrested without warrant of the civil authorities, tried by drumhead court martials, and given sentences in excess of any provided by the statutes.”

In a supplemental report, Sen. James Martine (D-N.J.) stated, “I charge that the hiring of armed bodies of men by private mine owners and other corporations and the use of steel armored trains, machine guns and bloodhounds on defenseless women and children is but a little way removed from barbarism.”

The committee pointed out that after national attention was drawn to the crisis in West Virginia (and to Jones’ arrest and detention) and the Senate investigation was initiated, martial law ended and civil law and authority fully established. It even stated that relations between the operators and miners “have become friendly and conciliatory.” The arrested miners were released.

Jones, who had received a 20-year sentence from a military court, was in the free and clear. She exclaimed, “Senator Kern threw open the prison doors for me.”

Later in 1913, she joined the campaign to organize miners in Colorado that became part of the Colorado Coalfield War. She was again arrested and imprisoned in a hospital before being escorted out of the state. She continued working as a UMW organizer into the 1920s and died in 1930.

Kern had succeeded. The Senate went on to launch similar investigations of copper mining in Michigan and coal mining in Colorado. But there was no big political payback for him. Kern had been a prominent proponent of the 17th Amendment, which modified the Constitution to implement the direct election of senators. The measure was ratified in April 1913, just as Kern started his crusade for an investigation of the coal industry in West Virginia. Three years later, under the new system for selecting senators, he narrowly lost his bid for reelection. He died in 1917. Over a century later, he is not much remembered.

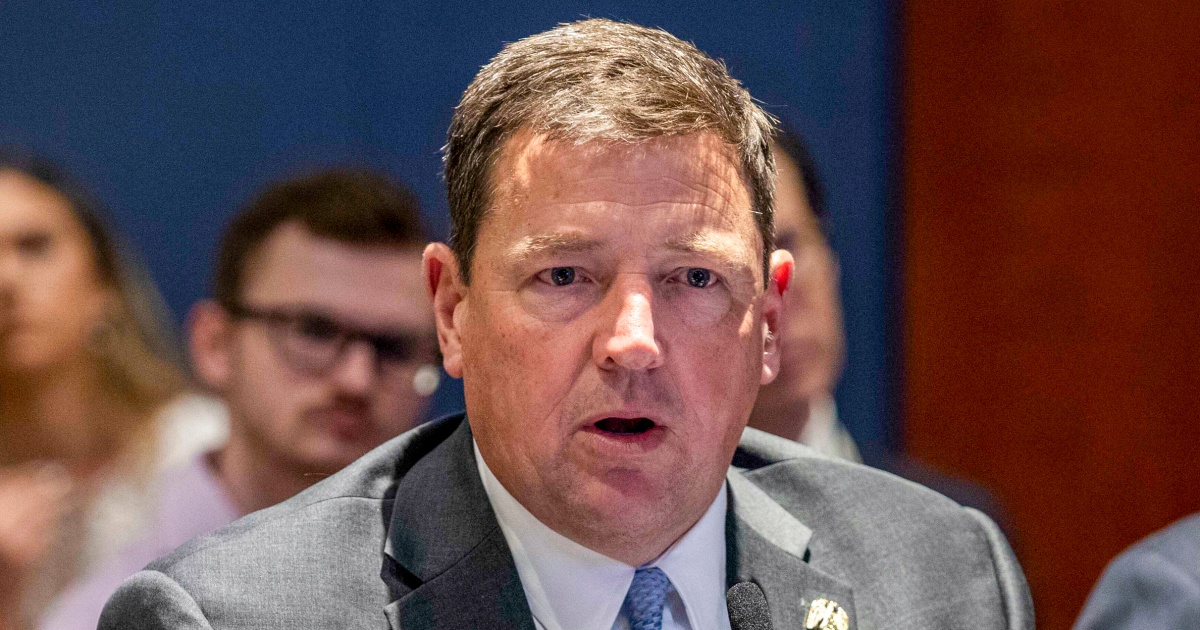

The unlikely duo of Kern, a Democratic lawmaker, and Jones, a socialist, worked together to reveal the abuses of the rapacious coal companies and to challenge corporate power—to advance the rights of West Virginia workers. Now, the descendants of those workers are largely pro-Trump. In 2016, they believed—or wanted to believe—Donald Trump’s claim that he would bring back coal jobs. Yet over his four years in the White House, coal mining employment fell 23.6 percent, and coal production declined 31.5 percent. Still, West Virginia remains solidly a red state. So much so that Sen. Joe Manchin, the conservative Democrat, decided not to run for reelection. The leading candidate for his replacement is outgoing GOP Gov. Jim Justice, whose coal business had a long history of safety problems.

Over the recent decades, the coal miners of West Virginia, for an assortment of reasons, have become aligned with conservative forces that are now led in the state by a coal baron. How symbolic. This turnaround is an example of the larger political shifts that have weakened the bond between white working-class Americans and the Democrats. The tale of the Kern resolution and what came afterward is a reminder that no political alliances are set in stone, and that the Democrats and progressives possess a pro-worker legacy that is readily available for revitalization.

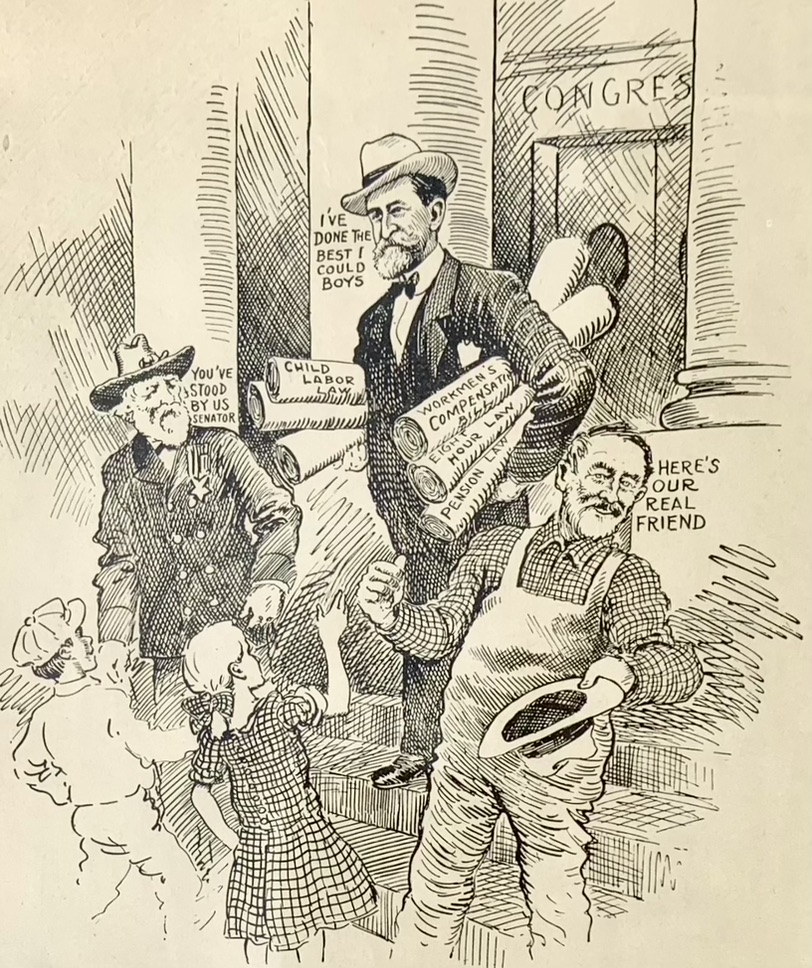

PS: Below is a political cartoon that extolled Kern’s populist progressive record. The accompanying text noted that he “forced the passage of Indiana’s first Employers’ Liability Law and first Child Labor Law through the Indiana Legislature in 1893.” It added, “He won the first straight out fight ever waged in the Senate between the lowly and the combined forces of plutocracy when he forced an investigation of the horrible conditions in the coal fields of West Virginia, and stopped the trying of miners by drum head court martials.”

David Corn’s American Psychosis: A Historical Investigation of How the Republican Party Went Crazy, a New York Times bestseller, has been released in a new and expanded paperback edition.