When the US targeted Russia’s oligarchs after the invasion of Ukraine, the trail of assets kept leading to our own backyard. Not only had our nation become a haven for shady foreign money, but we were also incubating a familiar class of yacht-owning, industry-dominating, resource-extracting billionaires. In the January + February 2024 issue of our magazine, we investigate the rise of American Oligarchy—and what it means for the rest of us. You can read all the pieces here.

On December 3, 1901, in his first annual message to Congress, Teddy Roosevelt began to articulate the new anti-monopoly doctrine that would define his presidency. “Great corporations exist only because they are created and safeguarded by our institutions,” he said in the address, read aloud to Congress by a succession of clerks who took turns slogging through the 80-page, leatherbound volume, “and it is therefore our right and our duty to see that they work in harmony with these institutions.” He asserted that the federal government should assume “power of supervision and regulation over all corporations doing an interstate business.”

The US economy had by then undergone decades of consolidation in which entire industries—oil, steel, sugar, tobacco, whiskey—were swallowed up into trusts, monopolistic arrangements wherein unlimited corporate assets, operating in a multitude of states, could be controlled by a single entity. America’s railroads, the arterial system of the economy, weren’t yet an outright monopoly, but things were barreling in that direction—they were ruled largely by six factions, which commanded about 165,000 of the nation’s 204,000 miles of trackage.

Northern Securities, formed in November 1901 under the permissive corporate laws of New Jersey, represented a new leap in the concentration of railroad ownership. This massive holding company (a new twist on the trust concept) controlled the Northern Pacific; Great Northern; and Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy railroads, whose lines collectively dominated northwestern rail traffic, and its board contained representatives of many of the six major railroad interests, including the Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, and Goulds.

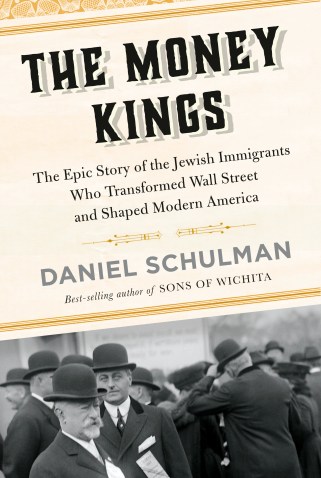

This article is adapted from Daniel Schulman’s new book, out Tuesday, The Money Kings: The Epic Story of the Jewish Immigrants Who Transformed Wall Street and Shaped Modern America.

To Roosevelt, this budding monopoly was an irresistible test case of the government’s regulatory clout. Several months after his speech, his administration sued to dismantle Northern Securities under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, an 1890 law that had mostly lain dormant since its passage. The case eventually rose to the Supreme Court, which, in March 1904, sided with the administration in a 5–4 decision. Roosevelt went on to use the Sherman Act—and the precedent set by the Northern Securities case—to sue dozens of trusts, including John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil monopoly.

The Pujo Committee, pictured in 1912.

Library of Congress

The episode would help to usher in a transformative period of corporate, regulatory, and financial reform that permanently altered the relationship between the government and corporations. In its wake, state and federal inquires proliferated—the Interstate Commerce Commission pursued a wide-ranging probe into the railroad industry and its barons; New York lawmakers held hearings on insurance industry corruption; and the Justice Department launched a series of antitrust investigations into the steel, meatpacking, and oil industries. Each inquiry revealed something different, but also similar: a relatively small group of tycoons reigning over vital swaths of the economy. They had amassed power that rivaled the federal government’s own, a point underscored vividly in 1907, when a financial panic that began on Wall Street sent the nation into a tailspin, and J.P. Morgan, playing the role of central banker when the nation still lacked a central bank, personally orchestrated the rescue of ailing banks and even New York City itself.

In the aftermath of that panic, congressional populists—with Rep. Charles Lindbergh of Minnesota, father of the famous aviator, at their vanguard—began pushing for an aggressive probe into the monopoly they contended was at the root of all the rest, a “money trust” of financiers who, by controlling the flow of capital and credit, had gained a stranglehold on the American economy.

The sensational probe that resulted, led by Arsène Pujo, Democratic chair of the House Banking Committee, cast a long shadow, hovering over decades of congressional debate and influencing the 20th century’s most pivotal banking and financial laws. “Few congressional investigations in American history have had more lasting impact on public policy,” noted the economic historian Vincent Carosso.

The Pujo Committee marked the moment when America was yanked back from the brink of outright plutocracy. And this episode—what led to it and what it led to—is particularly relevant now that the nation has drifted into what some historians have dubbed a new Gilded Age, dominated by a different type of monopoly and mogul but presenting similar pitfalls and perils. Staggering inequality, worsening labor strife, rapid corporate consolidation, crescendoing nativism and nationalism—there are many rhymes between that era and this one. Sub in Bezos, Gates, Musk, and Zuckerberg for the industrial barons of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and familiar themes are playing out.

“We have managed to recreate both the economics and politics of a century ago—the first Gilded Age,” wrote Columbia University legal scholar Tim Wu, who helped devise the Biden administration’s antitrust agenda, in his 2018 book, The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age. “As that era taught us, extreme economic concentration yields gross inequality and material suffering, feeding an appetite for nationalistic and extremist leadership.”

In other words, the United States may have reached another crossroads in the future of democracy itself.

The partners of J.P. Morgan & Co. called him “the Beast.”

Samuel Untermyer, general counsel of the Pujo Committee, built a multimillion-dollar fortune representing corporations during the frenzy of consolidation of the Gilded Age. “He was instrumental in forming a good many of the so-called trusts, and made a great deal of money out of it,” remembered Herbert Lehman, whose family firm, Lehman Brothers, was a client. Untermyer “had one of the keenest minds that I’ve ever known, and was one of the best cross-examiners that I’ve ever heard,” Lehman said. “Ruthless. Perfectly ruthless.”

But Untermyer’s inside view of the business world had gradually transformed the mustachioed lawyer into a crusader for reform who warned of “a moneyed oligarchy more despotic and more dangerous to industrial freedom than anything civilization has ever known” and who called for curbing the “concentration of the money power.” In 1912, he set aside his lucrative legal practice to lead the congressional investigation into the “money trust.”

His appointment to the panel struck fear into the hearts of the nation’s financiers because few men were as familiar with their schemes and tactics.

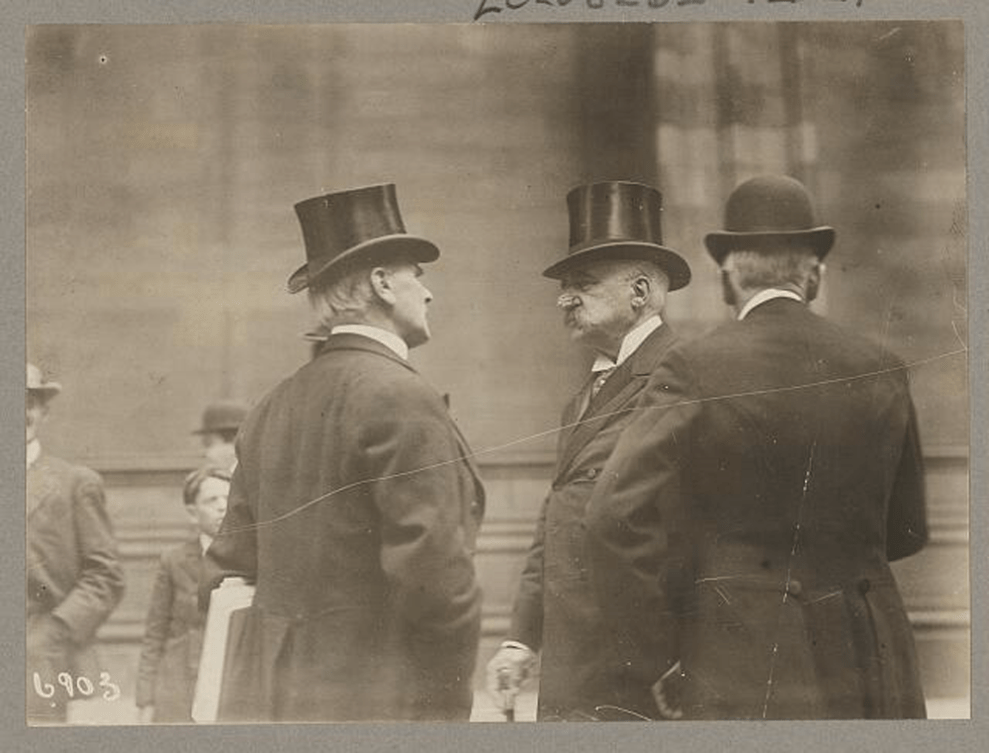

J.P. Morgan, circa 1907, facing left with two acquaintances.

Library of Congress

Before the committee came a parade of moguls, but no banker’s appearance was more closely watched than that of J.P. Morgan, so synonymous with creating monopolies that the technique he perfected to an art form was named after him—“Morganization.” A decade earlier he had been one of the primary combatants in the “Battle of the Giants,” as it was dubbed, that had led to the formation of Northern Securities. On the other side of that struggle was Jacob Schiff, another high-profile Pujo Committee witness and a senior partner at the investment bank Kuhn Loeb.

Morgan and Schiff were the undisputed heads of two distinct Wall Street camps—Morgan the leader of the patrician “Yankee” bankers with New England roots, and Schiff the chieftain of the ascendant German Jews, whose mighty houses, including Goldman Sachs and Lehman Brothers (with which Kuhn Loeb would later merge), had risen from modest mercantile origins.

Technically rivals, Morgan and Schiff generally found it more profitable to be allies than enemies. They formed “communities of interest,” a rosy euphemism for monopolistic alliances that typically involved companies holding shares in their competitors to incentivize cooperation. But when their respective associates pursued the same Midwestern rail line, Schiff and Morgan were propelled into a skirmish that touched off a financial panic that caused, by one estimate, some $10 million in investor losses. One distraught Wall Street operator reportedly drowned himself in a vat of hot beer. (For a more detailed account of their clash, read my new book, The Money Kings, from which this piece is adapted.)

Beset by lawsuits and public outrage—“Oh, it is excellent to have a giant’s strength; but it is tyrannous to use it like a giant,” the New York Times thundered, quoting Shakespeare—the Schiff and Morgan cadres forged a compromise, creating a colossal new community of interest: Northern Securities. It was this display of unbridled financial might that eventually landed them in the Pujo Committee’s hearing room.

Morgan testified for two days in December 1912. Seventy-five and in flagging health, the lion of American finance seemed almost docile. Hunched in a flimsy rattan chair, he spoke in a low monotone, his eyes occasionally wandering over the crowd of hundreds who had gathered to watch his interrogation. Instead of the brusque and impetuous robber baron of popular legend, Morgan displayed an “almost extravagant politeness,” one newspaper reported.

“When a man has got a vast power, such as you have—you admit you have, do you not?” Untermyer probed in one exchange.

“I do not know it, sir,” the banker replied.

“You admit you have, do you not?”

“I do not think I have.”

“You do not feel it at all?”

“No, I do not feel it at all.”

Untermyer displayed charts that told a different story. They showed the overlapping relationships between 18 firms that possessed vast influence over banks, trust companies, insurers, utilities, railroads, and other corporations. One hundred and eighty representatives of these outfits, the committee determined, held 746 directorships in 134 corporations that controlled more than 13 percent of the nation’s total assets. The investigation illustrated what had become obvious to most Americans—the yawning imbalance between those at the top of the financial pyramid and those below, and the astonishing power wielded by a fraternity of moguls who dictated the rules.

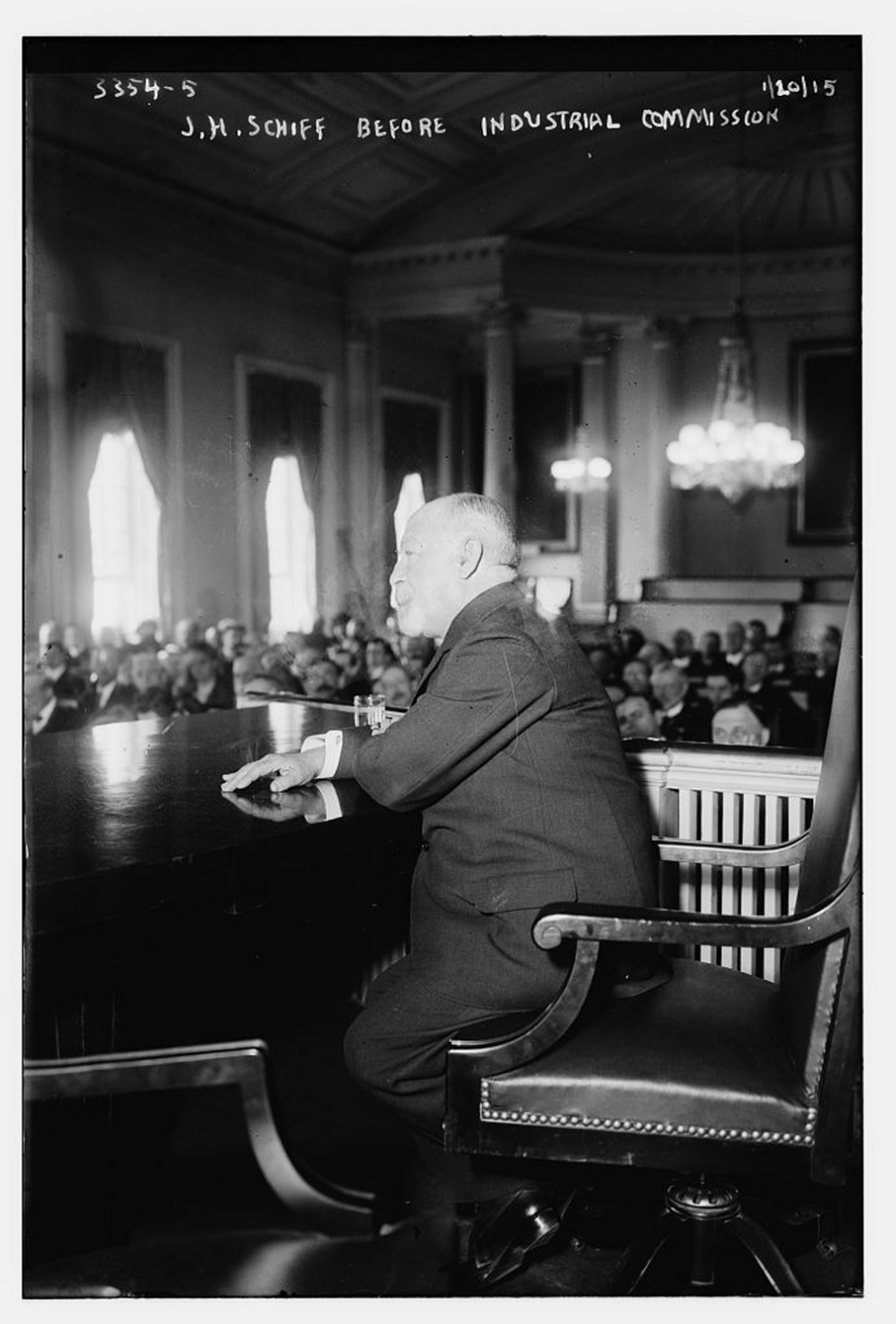

In January 1913, a month after Morgan’s grilling, Schiff appeared before the committee, where Untermyer quizzed him about Kuhn Loeb’s banking “alliances.”

“I cannot call them alliances,” Schiff demurred. “We have correspondents and friends that cooperate with us, but we are not allied to anybody.” He called monopolies “odious” and said he did not believe in concentrating corporate power through holding companies (though this is precisely what he and Morgan had done with Northern Securities). But he also said, “I would not limit the individual by law to buy whatever he pleases.”

“Even if it amounted to a monopoly?” Untermyer asked.

“Even if it amounted to a monopoly.”

Untermyer dug further. “I want to know where you would draw the line with respect to the license you would give to individuals to get control of any industry or any line of busines.”

“I would let nature take its course,” Schiff said. “I would not limit, in any instance, individual freedom in anything, because I believe the law of nature governs that better than any law of man.”

The Pujo Committee released its findings in late February 1913, identifying J.P. Morgan & Co. and Kuhn Loeb as two of six primary “agents of concentration.” If the panel fell short of proving a “money trust” in a literal sense, it succeeded in showing in stark terms how concentrated corporate power had become. The six firms’ representatives served on a dizzying assortment of boards and wielded immense financial strength, including the ability to stifle competition and starve would-be rivals of credit. A month after the probe concluded, word came from Rome that J.P. Morgan had died, expiring in a $500-a-night hotel suite. His son, Jack, blamed the investigation and his father’s public grilling by “the Beast.”

The Pujo Committee generated front-page headlines, but it was Louis Brandeis, the prominent lawyer and anti-monopolist, who amplified its findings in a way that resonated more deeply with the public. In a series of essays in Harper’s Weekly—also collected into a book called Other People’s Money: And How the Bankers Use It—Brandeis crisply distilled what Untermyer and his colleagues were uncovering. “The dominant factor in our financial oligarchy is the investment banker,” he wrote in one article. “Associated banks, trust companies and life insurance companies are his tools. Controlled railroads, public service and industrial corporations are his subjects…these bankers bestride as masters America’s business world, so that practically no large enterprise can be undertaken successfully without their participation or approval.”

Jacob H. Schiff testifies before the Commission on Industrial Relations at New York City Hall in January 1915.

Library of Congress

As a chief economic adviser to Woodrow Wilson, who became president shortly after the Pujo Committee concluded its work, Brandeis helped inspire Wilson’s “New Freedom” agenda of banking and corporate reforms. By 1914, Congress had passed the Clayton Antitrust Act (strengthening the Sherman Act) and created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to crack down on monopolistic practices. Later that year, the Federal Reserve opened its doors. The product of years of political skirmishing, the Fed—which included a network of regional reserve banks to assuage detractors who feared the “money trust” would use a standalone central bank to strengthen its grip on power—ushered in a new era of banking and brought Wall Street into partnership with the government as never before.

Wilson appointed Brandeis to the Supreme Court in 1916, where he remained for two decades. “No one was more responsible for the Pujo subcommittee’s lasting impact than Louis D. Brandeis,” who “influenced the direction of American politics for nearly two generations,” noted historian Carosso.

More than a century later, the philosophy of “the people’s lawyer,” as Brandeis was known, is again ascendant in Washington, challenging the long-dominant free-market orthodoxy of Milton Friedman’s Chicago School. The Biden administration has filled key regulatory roles with prominent members of the New Brandeis Movement. Besides Wu, who served for nearly two years on the National Economic Council before returning to academia last January, this includes Jonathan Kanter, who oversees the Justice Department’s antitrust division, and FTC chair Lina Khan. “Brandeis and many of his contemporaries feared that concentration of economic power aids the concentration of political power, and that such private power can itself undermine and overwhelm public government,” Khan wrote in 2018.

If the monopolies of the Gilded Age jeopardized democracy, today’s tech conglomerates magnify risks to the political system, especially given their power over the flow of information. Though their virtual sprawl is harder to visualize than the railroad kingdoms of the Gilded Age, the effect is similar. From how we search the internet (and what we find) to the way we share news and interact with fast-evolving artificial intelligence—tech firms control the chokepoints of a digital infrastructure that, for better or worse, has become essential to our lives.

Joe Biden, once seen as so simpatico with banking interests that he was dubbed the “Senator from MBNA,” has pursued a far more progressive agenda as president, and by placing Khan at the helm of the FTC, he sent an unmistakable signal about his antitrust priorities. Her agency, in concert with the Justice Department, has moved swiftly to bring Big Tech to heel, filing antitrust cases against Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Meta (formerly Facebook). Both Amazon and Meta have sought her recusal from cases against their companies.

As they take on modern conglomerates, regulators largely rely on the legal tools created more than a century ago. For decades, there has been little movement on updating the nation’s antitrust laws, but recently, taking on tech monopolies has become a rare area of bipartisan consensus. In late 2022, antitrust reformers pushed an ambitious slate of measures to the brink of passage in the year-end omnibus bill. The two most consequential bills targeted tech firms: One, co-sponsored by Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), would potentially prevent online platforms from skewing search results for their benefit and engaging in other anti-competitive practices. Another, aimed at Apple and Google, would have prevented app purveyors from squeezing out rivals. At the last minute, both bills were blocked by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer from coming to a vote, but the spending legislation did include $85 million in new funding for antitrust enforcement.

That these measures made it as far as they did was a significant victory for antitrust advocates, as is the fact that, on left and right, the once sleepy topic of corporate concentration is again part of the national conversation. The antitrust momentum suggests the nation may be nearing an inflection point like the one that touched off Roosevelt’s trust-busting crusade.

“Antitrust has fallen into hibernation before as ideologies have shifted, only to come roaring back to meet the needs of the age,” Wu wrote in the Curse of Bigness. (The title is a nod to Brandeis, who wrote in one essay that “Bigness has been an important factor in the rise of the Money Trust.”)

Not long after leaving the Biden White House in January 2023, Wu spoke at the University of Chicago, birthplace of the conservative economic thinking that has influenced past presidential administrations to weaken antitrust enforcement, holding (as Schiff did during his testimony) that unfettered markets will regulate themselves more effectively than any government-imposed strictures can. Wu called the stalled antitrust bills “unfinished business” and described the animating forces behind the Biden administration’s antitrust philosophy. He did not mention Donald Trump, January 6, or the role tech platforms played in spreading conspiracy theories and disinformation that have badly frayed the fabric of our republic, but it was evident that the nation’s precarious state had influenced the Biden team’s thinking.

“Being concerned about democracy and authoritarianism” was “in the background of some of our efforts to make antitrust big and visible in people’s lives,” Wu said. And he invoked Roosevelt’s landmark antitrust case against Northern Securities, where the government took bold action to reclaim the power it had ceded to the nation’s tycoons. “In terms of giving people a sense that they are standing up for things—this is what Theodore Roosevelt did when he started enforcing in 1904. He said, ‘We need to show the people that the government rules this country, not the corporations.’”

Top illustration: Michael Waraksa; Source images: The Print Collector/Getty; Mustafa Yalcin/Anadolu Agency/Getty; John Thys/AFP/Getty