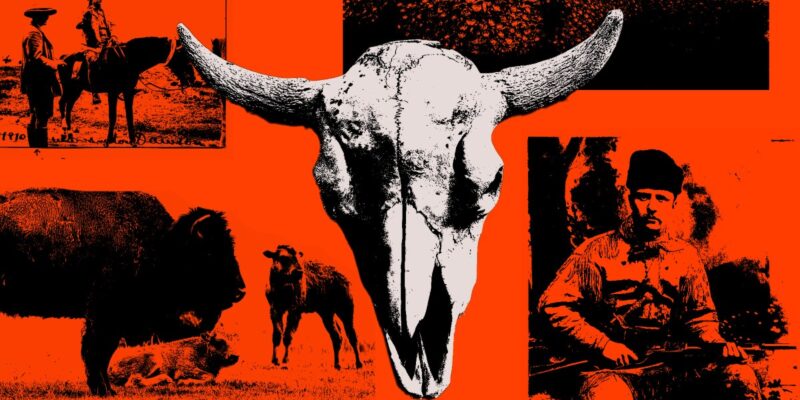

If you attended high school in the United States, you likely learned about the “Great Slaughter” of the American buffalo: During the 19th century, with the aid of the railroad, hide hunters poured into the Great Plains by the thousands, indiscriminately shooting buffalo (or, technically, “bison”) to collect their furs and tongues, which were sold as hairbrushes. At the same time, the US military actively encouraged the hunters in the hope tribes would be more easily forced onto reservations without their food supply. By the 1890s, hunters had slaughtered so many buffalo that the animals’ numbers, once in the tens of millions, had plummeted to less than 1,000 individuals.

The buffalo’s near extinction, along with the killing of other western mammals like elk and grizzly bears, is “the greatest murder of animals in the history of humankind,” says American documentary filmmaker Ken Burns. This bleak chapter in American history is the focus of the first half of Burns’ latest two-part documentary, The American Buffalo, which airs on PBS on October 16 and 17.

Today, there are more than 400,000 bison in the country. While most are in commercial herds, tens of thousands roam free. On paper, that’s a clear conservation success. But as part two of Burns’ film explores, the story of how America saved the species is a heck of a lot more complicated. As Burns shows, a collective effort by Native American families, reformed bison hunters, conservationists, and politicians helped bring the buffalo back—but some of those involved had questionable reasons for doing so.

William T. Hornaday, for instance, a taxidermist and conservationist, shot and killed some of the last remaining buffalo in order to put their stuffed skins on display at the Smithsonian, with the hope of inspiring conservation measures. He later went on to help found the Bronx Zoo with Madison Grant, a leading proponent of eugenics and author of the discredited book, The Passing of the Great Race. Hornaday shared many of Grant’s racist views: “The idea that citizens of the United States had driven this species extinct was offensive to him, was an outrage to him,” science journalist Michelle Nijhuis explains in the film. “But it was also tied up with his strong sense of racial superiority.”

Another member of the save-the-buffalo club was showman William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who traveled the world depicting “heroic” reenactments of adventures in the American West, including battles against Native Americans. Cody is credited with helping to bring the world’s attention to the bison’s dwindling numbers. But just years before, he had been among the hunters responsible for decimating the species.

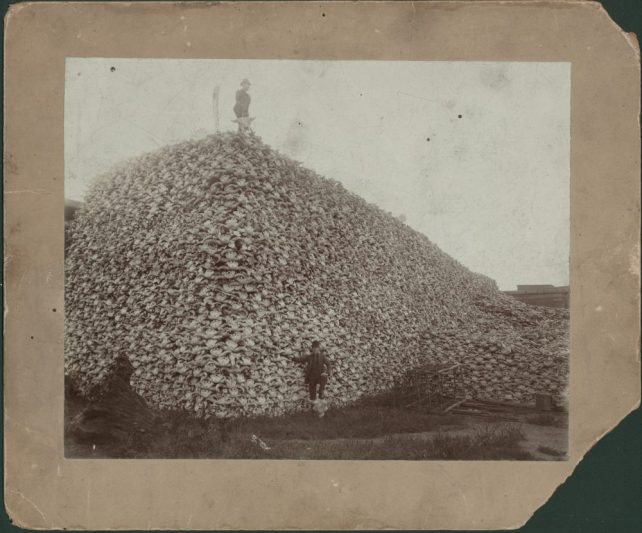

Two men stand with a pile of buffalo skulls in 1892.

And then there’s Theodore Roosevelt, who supported the first major reintroductions of bison in Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Montana. But Roosevelt also once wrote that killing the bison was something of a necessary evil because it was “the only way of solving the Indian question”: The buffalo’s disappearance, he wrote, was the “only method” of forcing Native Americans “to at least partially abandon their savage mode of life.”

These contradictions make the fall and rise of the buffalo, in Burns’ eyes, a uniquely American story. “It is both at the heart of the tragedy of the United States,” he told me in a conversation last month, “but also the possibilities.”

Burns hopes viewers will see the film as “the first two acts of a three-act play,” he says: “The third will be written by us, particularly by Native Americans, who are working to continue to grow and restore the country’s bison herds.” He hopes it can serve as a “hopeful roadmap” in addressing the mass extinctions the world is facing today.

Portrait of Theodore Roosevelt, seated, in deer skin hunting suit, holding rifle, 1885.

George Grantham Bain/Library of Congress

You can read an edited and condensed version of my conversation with Burns below:

One of the most interesting takeaways from your docuseries was that in large part, we have bad people—racists—to thank for the survival of the bison. And I was like, what do I make of that?

Yeah, so you have Charlie Goodnight in the panhandle of Texas, who was a Texas Ranger and an Indian-hater who couldn’t stand buffalo. He’s got the first ranch in Palo Duro Canyon, and he starts a buffalo herd for his wife because she’s 70 miles from the nearest neighbor and lonely. And suddenly he undergoes this amazing transformation: By the end of his life, he’s friends with Comanche leader Quanah Parker and helping to reintroduce buffalo.

And even Theodore Roosevelt, we have to acknowledge, is someone who had views that are reprehensible. He did believe that the extermination of the buffalo was probably good in the long run because it would help solve the “American Indian question,” which is cringe-worthy. Then he later goes a long way to save, specifically, the buffalo.

Some of the people who helped save the buffalo were also people who were saving it, as journalist Michelle Nijhuis says, “for the wrong reasons”—to prove a kind of supremacy. It’s “The White Man’s Burden,” noblesse oblige. That is—excuse my French—bullshit.

This conservation “success” story also feels like a failure to Native Americans. While white Americans mobilized to save the buffalo, as you note, the same effort was not extended to undo the harm that the American government did to Native Americans.

That’s the essence of the story. This is about the buffalo, but it’s really about the US government’s treatment of Native Americans. And it’s scandalous, it’s obscene. It’s a tragedy. For 150 years, many Plains tribes, and much longer for other Native peoples, had been disconnected from a major source of sustenance—they used everything from the tail to the snout—but also a source for significant religious and spiritual practices.

Although it wasn’t official policy of the United States government, [officials] thought that “If you killed the buffalo, you kill the Indian.” They knew the slaughter of the buffalo had an ancillary quote-benefit-unquote, in that it would starve the Native peoples in the Plains and make them more docile and willing to be herded into reservations and confined there and then to be Americanized. I mean, the “Friends of the Indian” said, “Kill the Indian, save the man.” They’re the ones—the progressives—who thought that their culture should be eradicated, their languages and customs should be eradicated; that you should place them in schools and punish them if they spoke their Native languages; dressed them in suits; cut their hair, an important symbol to them. These are the “Friends of the Indian.”

Native Americans are not absent from the story of the saving of the buffalo; at one point, most of the [county’s remaining] buffalo were in captivity in zoos and private herds. The two biggest herds were run by Native tribes. I think what is quite moving and powerful about the end of the story that we tell in our film is that it is both hopeful—in that Native peoples are beginning to repatriate with the buffalo—but we’re also asking, what is the United States’ complicity and responsibility in this tragedy?

You don’t make the case for this directly. But watching it, I felt like the film was an indirect call for reparations for Indigenous people. There’s a quote, for instance, from anthropologist George Bird Grinnell: “The most shameful chapter of American history is that in which is recorded the account of our dealings with the Indians. The story of our government’s relations with this race is an unbroken narrative of justice, fraud, and robbery.” Did you intend for the film to feel like that?

It’s a complicated story, and it does not shy away from that. If people were to interpret [the film] as saying, these were sins that we need to atone for, that would be okay with me. But we’re not telling people—there’s no, What would you like people to take away from that? It’s a really complicated story about us. And we’re all involved in it. And it’s a tragedy, and it’s also extraordinarily uplifting. The buffalo is not going to go extinct. It was in danger. There may have been fewer than 25, wild and free, in Yellowstone. Now there are hundreds of thousands in federal hands, Native hands, and private ownerships.

We’re trying to suggest that there’s a Third Act that needs to be written by all of us. It is intertwined with our climate disaster. It is intertwined with our incredibly painful history. At the beginning of episode two, there’s a [Wallace] Stegner quote: “We are the most dangerous species of life on the planet, and every other species, even the earth itself, has cause to fear our power to exterminate. But we are also the only species which, when it chooses to do so, will go to great effort to save what it might destroy.” And so the question is, can you save the buffalo? Can you save the planet?

We’re living through a climate crisis and a biodiversity crisis. Is there anything to learn from the bison story to prepare us for this moment?

We’re at a moment in the history of our planet when we may begin to see many large mammals going extinct. The story of the buffalo offers human beings a hopeful roadmap to what it might look like to try to reverse this. It was a man-made slaughter that diminished the buffalo. We are in a place where what we have done to our environment, man-made again, is going to eliminate lots of big mammals in addition to thousands of other species. And we are obligated, it seems to me, to use the story of the buffalo—the mistakes as well as the positive steps—to help us in our effort to save not only other animals, but our planet and, therefore, ourselves.

Would you say the story of the American buffalo is something to be ashamed of or celebrated?

There is a neon sign I put in our editing room a dozen years ago that says in lowercase cursive, It’s complicated, to remind ourselves to always dig deep, to include all parts of a story. So, let me let me fall back on that—it’s complicated.

I mean, I’ve made the same film, over and over again. Each film asks one deceptively simple question: Who are we? Who are those strange and complicated people who like to call themselves Americans? And what does an investigation of the past tell us about not only where we’ve been, but where are we now? And where may we be going?

We have this task, both individually, socially, and nationally, in a broad sense, of being responsible for our history and trying to be better, whatever better is. That’s the whole job. This is where I operate—between the majesty, complexity, contradiction, and controversy of the US and all of the intimacy of the lowercase us. And that’s where this buffalo story finds itself.