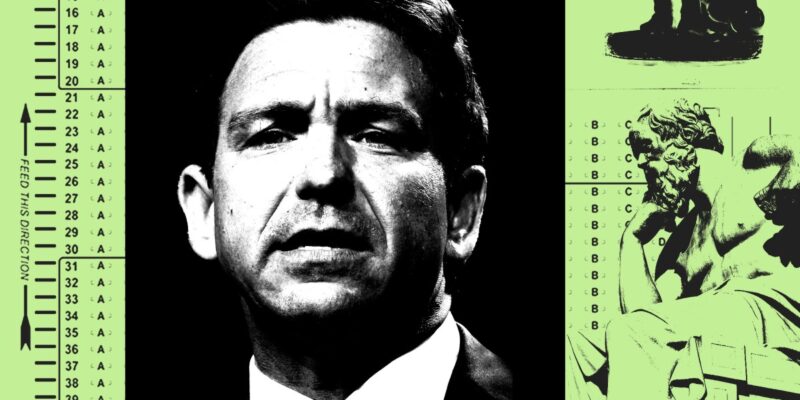

In his crusade to stamp out progressivism in his home state, Florida Governor and presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis has made a particular obsession out of de-woke-ifying education: He has passed legislation that made it illegal for elementary school teachers even to mention LGBTQ families. He convened a committee to scour textbooks and reject those in which they detected any whiff of anti-racist content or a passing reference to socialism. His administration has endorsed history curriculum that teaches students that Black people benefitted from slavery.

Most recently, DeSantis has gone hard against the College Board, the nonprofit that administers the SAT college entrance exam along with high school Advanced Placement tests. In January, the DeSantis administration announced that it would not allow Florida high schools to offer the AP African American history course, claiming that it “significantly lacks educational value.” At a February press conference, he hinted that Florida might try to break ties with the College Board entirely. “It’s not clear to me,” he said at a February press conference, “that this particular operator is the one that’s going to need to be used in the future.”

#BREAKING: Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) doubles down on his opposition to the College Board’s AP classes, asking, “Who elected them?” pic.twitter.com/vYcsyvb3SS

— Forbes (@Forbes) February 14, 2023

It’s one thing to jettison a few woke textbooks, but quite another to ditch the SAT altogether. Certainly, its dominance has diminished in recent years. Some colleges have stopped requiring applicants to submit scores from the SAT and its competitor, the ACT. But the SAT is still the prevailing college entrance exam: According to the College Board, 1.7 million American students took it last year, about 190,000 of them in Florida.

But what’s a few million customers compared to an opportunity to own the libs? In June, a Florida Board of Governors committee moved to allow prospective students at the state’s public universities to submit an alternative to the SAT: an exam called the Classic Learning Test that says it focuses on “meaningful pieces of literature that have stood the test of time.” The test, which Florida already accepts as a qualifying exam for its largest scholarship program, is part of an ascendant movement of classical education, which emphasizes classic works of literature taught through the Socratic method, in which teachers use a series of provocative questions to help students draw conclusions about a text. Some classical schools have become known for their political conservatism—a leader in the movement is a network of K-12 classical charter schools founded by Hillsdale College, a small Christian school that has had an outsize influence on right-wing politics in recent years. Presumably, the DeSantis administration assumes that a classical test must, almost by definition, eschew progressivism. They might be surprised to find out that the makers of the test are deeply ambivalent about being dragged into the culture war.

Founded in 2015, the Classic Learning Test company says its mission is “to reconnect knowledge and virtue by providing meaningful assessments and connections to seekers of truth, goodness, and beauty.” It hopes to accomplish this goal through a suite of standardized tests that draw from the works of the great thinkers and writers of the Western intellectual tradition—Plato, Homer, Dante, Tolstoy, Melville, and C.S. Lewis, to name but a few. So far, about 250 colleges and universities—most of them Christian—accept the Classic Learning Test as an alternative to the SAT and ACT.

I wondered what was actually on the Classic Learning Test, so I decided to see for myself. I called up Harry Feder, an attorney and former schoolteacher who now serves as the executive director of FairTest, a group that advocates for equity in standardized testing. Feder and I met over Zoom to look at a Classic Learning Test practice exam together. First up was the verbal reasoning section, which included passages from the ancient Mesopotamian poem The Epic of Gilgamesh, the writings of the Carmelite nun St. Teresa of Avila who lived in the 1500s, Plato, and the classic American history founding text, the Federalist Papers.

Feder, who once taught Princeton Review test prep courses, showed me some tricks. Even without reading the passage, he said, you can usually look at the questions and eliminate some obviously wrong answers first. For example, here’s a question about the passage from Plato:

According to Passage 1, a man can minimize the lawless wild-beast nature inside of him by:

A) getting enough sleep.

B) accepting his own corruption.

C) practicing his powers of rationality.

D) fighting against tyranny.

Right off the bat, we eliminated D (didn’t quite make sense) and A (didn’t seem…relevant to Plato’s interests?). So that left B and C. Practicing rationality seemed a more practical approach to taming your inner lawless beast than accepting your own corruption—whatever that meant. So C was our choice—and we were right! That was even without referring back to the text. The questions in the grammar and writing and math sections seemed to be equally divorced from the source material.

Feder observed that while the passages were different from those included on the SAT, the style of questions appeared to be essentially the same. This test certainly didn’t solve the problem of equity—like most standardized tests, it seemed to privilege students who had learned test-taking tricks. This was disappointing for Feder, who told me that he loves the idea of giving students an opportunity to wrestle with life’s great questions. He became particularly animated when we looked at the Classic Learning Test “author bank”—the list of source material that the test draws from—and he noticed Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the Soviet dissident philosopher who wrote about life in the Russian gulags. “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich—have you read that?” he asked.

“No,” I admitted.

“Oh, go read it,” he said. “It’s short. It’s a day in the life of a prisoner, and it’s these great existentialist questions. How do you fight authority? What is the value of work? And questions of God.” To reduce all that to a reading comprehension question that has only one right answer struck Feder as “just preposterous.” Wouldn’t it be more interesting to discuss Plato’s thoughts on man’s “lawless beast nature” rather than to answer a banal question about a short passage on it?

I raised Feder’s criticism when I spoke with Jeremy Tate, the founder of Classic Learning Test. “The test itself seems to rely on some of the same skills” as the SAT, I offered.

“Totally,” he said. “And this is where it gets really tricky.”

Like Feder, Tate is also a former teacher. He explained that he never aspired to be a test magnate. His interest is in classical education itself, a consequence of his experience teaching in schools in poor communities with few resources, where he had trouble motivating his students. He’s convinced that American schools would be more engaging and effective if students were given the opportunity to go deep into texts that illuminate truths about the human condition. “When I was teaching about something like the Holocaust, suddenly even the most checked out kid was very, very interested,” he said. “I think there’s this natural curiosity about the human capacity for good and the human capacity for evil.” If he could devise a standardized test that drew from works that dealt with these timeless questions, he reasoned, then curriculum change might follow. But to make his test competitive with the SATs and the ACTs, it essentially had to measure the same things, which are called, in testing lingo, concordance. “If we’re measuring totally different things, there’s no way we can have a concordance chart,” he said, “which is what we knew we would need for colleges to adopt it.”

Right before he founded the company in 2015, Tate was running a test prep company and working as a college counselor. Admissions officers told him that they would welcome an alternative to the SAT, so Tate set to work on developing a test that reflected the texts and questions he had grown to love teaching. He hired freelance test developers to create the first pilot test, and with the help of an initial investment from a college buddy, Tate became the first full-time employee in 2016. Tate declined to tell me how many students take the test annually, but he noted that the company now has 25 employees.

While some proponents of classical education focus only on European and American literature, Tate believes that texts from other traditions can be equally valuable. Over the last few years, he and his team have been expanding their “author bank” to draw from works that have largely been left out of discussions around the canon adding the likes of Mahatma Gandhi, Langston Hughes, Jorge Luis Borges, and Toni Morrison, to the stalwarts of Plato, Homer, the Founding Fathers, Milton, Locke, and Hume.

Not everyone celebrated this development—especially classical education purists. Writing in the American Conservative in April, Matthew Freeman, whose bio describes him as “an educational administrator and editor from California,” accused Tate of allowing his test to be corrupted by the leftist ideals of diversity, equity, and inclusion. “Using the tradition as a tool for some egalitarian project of social uplift will cause the tool to swing back and strike the workman himself,” he predicted. “The moment you agree to play the left’s game, they secure the victory.”

When I asked Tate what he thought about that criticism, he sighed. “I get called a woke influence on the classical education movement, and I get called right-wing by people outside of it,” he said. “Everybody wants to put everything in a box. And that’s because we don’t know how to think outside of political categories.” To be clear, Tate himself is not entirely above that fray: On X, his recent reposts include culture war provocations by presidential candidates Vivek Ramaswamy and Ron DeSantis, and anti-abortion activist Lila Rose. He told me that he identifies as a political conservative and a Catholic, and he believes that parents should have an option to use voucher funds to send their children to religious schools.

Despite those right-wing bona fides, he explained that he was trying to transcend political partisanship in assembling the Classic Learning Test’s board: It included crusading conservative education activist Christopher Rufo, but also philosopher Cornel West, who is currently running for president as a Green Party candidate. Between these two extremes is a collection of other educational leaders—it’s heavy on the conservative thinkers but also includes some left-leaning academics—who help Tate and his team shape the tests.

The chair of Tate’s board, Angel Adams Parham, a University of Virginia sociologist who studies race, scoffed at the notion that the act of expanding the author bank to include more diverse voices could somehow dilute the value of the test. Parham, who is Black and wrote a book last year called The Black Intellectual Tradition, said that she had “a very different take on classical education,” one that she didn’t see reflected in media coverage of the movement. That the test had become ensnared in the culture wars, she said, was “really unfortunate.” Along with her fellow board member and co-author Anika Prather, a professor of education at Johns Hopkins University, Adams has led the charge at Classic Learning Test to expand the author bank. I remarked to Adams that it must be interesting for her to serve on the Classic Learning Test board alongside ideologues like, say Rufo. She laughed. “Interesting is one word for it,” she said.

On Tuesday, Florida’s Board of Governors will decide whether the state’s public universities will accept the Classic Learning Test as an alternative to the SAT. The College Board is likely aware of this inflection point: Last month, the group issued a statement criticizing the Classic Learning Test’s concordance study, finding problems with its methodology. If the committee endorses the test, DeSantis will likely count it as a victory in his war against the College Board. But for Tate, the prospect of his test getting the DeSantis stamp of approval contains some genuine perils. He is worried that the stain of partisan politics could backfire in the long run. “Okay, so DeSantis does this, and then the wannabe DeSantis governors are going to also do it, and then CLT becomes like this red-state test,” he said. “I don’t think that’s a good thing.”