Seventy-eight years ago today, on August 9, 1945, the US military detonated a powerful atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Nagasaki, ultimately killing as many as 90,000 people, nearly all civilians. Yet Nagasaki today might as well be called the “forgotten A-bomb city.” Every August, media and public attention focuses overwhelmingly on Hiroshima, site of the first blast three days earlier—though the attack on Nagasaki was in many ways even more questionable and appalling.

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer did nothing to change that narrative. The Nolan film, as I noted in my Mother Jones recap, barely mentions the Nagasaki bombing, and when it does, it’s a parenthetical or an awkward reference, such as when one character cites the destruction in Hiroshima and Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) adds, “and Nagasaki.” This is unfortunate, especially since the real-life Oppenheimer exhibited few qualms about the massive loss of life in Hiroshima but appeared haunted and possibly regretful in the wake of the Nagasaki bombing.

Some of the other scientists at Los Alamos who celebrated the Hiroshima bomb would later claim they felt physically sick upon learning of the second attack. “Dropping the bomb on Hiroshima was a mistake,” Samuel I. Allison, a leading Manhattan Project scientist at the Met Lab in Chicago, declared years later. “Dropping the bomb on Nagasaki was an atrocity.” While historians remain divided on the justification for bombing Hiroshima, even some supporters of the first attack declared the Nagasaki annihilation avoidable. Telford Taylor, chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Nazi trials, asserted that while the “rights and wrong of Hiroshima are debatable” he had “never heard a plausible justification of Nagasaki.”

The history of Hollywood downplaying Nagasaki goes back to 1947 and the first movie drama about the bomb, MGM’s The Beginning or the End. As development progressed on that film, the Nagasaki attack gradually lost its place in the script and in the end it received no mention at all. You could watch that film start to finish and have no idea we even dropped a second bomb. Oppenheimer does a bit better than that, at least.

From the start, whenever the attacks on Japan were recalled in the media, that one word, “Hiroshima,” was inevitably used as shorthand for both. This left Nagasaki to sink almost into oblivion. Few journalists bothered to visit. Nobody ever wrote the Nagasaki counterpart to John Hershey’s Hiroshima or produced a film titled, Nagasaki, Mon Amour. “We are an asterisk,” Shinji Takahashi, a Nagasaki sociologist, told me with some bitterness when I visited the city.

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., who survived the firebombing of Dresden in World War II, would later say, “The most racist, nastiest act by this country, after human slavery, was the bombing of Nagasaki.” He described it as “purely blowing away yellow men, women, and children. I’m glad I’m not a scientist because I’d feel so guilty now.” Footage of gruesomely injured Nagasaki civilians, most of them women and children, taken by Japanese and US Army teams after the war, would be buried by American officials for decades.

Nagasaki, with a population of 250,000, served as an important site for Mitsubishi’s industrial war effort, but by 1945 the Allies’ blockade of Japan was severely cutting production. Few Japanese soldiers were stationed there—far less than in Hiroshima—and only about 250 would perish as a result of the Nagasaki blast, along with several Dutch POWs.

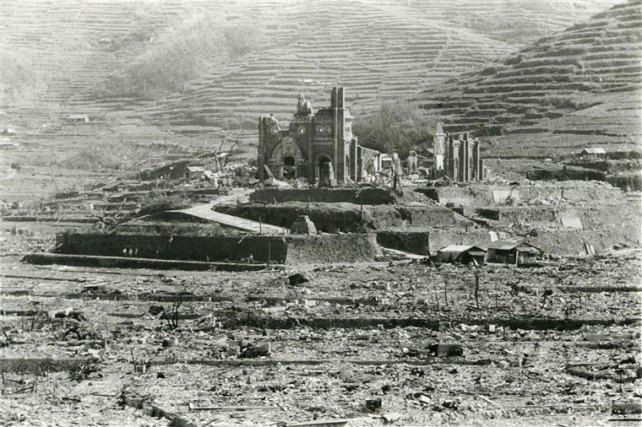

The second bomb was actually intended for Kokura, but in a lucky break for its residents, the city was obscured by clouds, and the B-29 shuttling the “Fat Man” was rerouted to Nagasaki. This plutonium bomb had a yield of 22 kilotons, almost double the destructive power of the uranium bomb deployed against Hiroshima. It exploded more than a mile off target, detonating almost directly over the cathedral (the largest in the Far East) in the Urakami district, home to most of Nagasaki’s 10,000 Catholics. The blast rippled up the narrow Urakami Valley but didn’t reach the city’s congested harbor area or climb any major ridge. Had it exploded over the city center, its toll would have made Hiroshima, in one important sense, the Second City. Nothing alive would have escaped, perhaps not even the most untroubled conscience half a world away.

One has to wonder about the impulse to almost immediately deploy a second bomb, and one far more powerful than the first. Why didn’t Truman step in after Hiroshima and give Japan a few more days to contemplate surrender before targeting another civilian population for extinction? The United States knew its ally, the Soviet Union, would join the war within hours, as previously agreed upon, and that the entrance of this mortal enemy of Japan would likely speed the surrender. (Indeed, as I noted previously, Truman wrote in his diary that Stalin’s promise to attack Japan meant “Fini Japs,” with or without the use of America’s new weapon.)

If the USSR jumped in, however, it might have prompted a wider Soviet claim on Japanese conquests in Asia. In short, US military officials felt there was much to gain by getting the war over before the Russians advanced. In that sense, the Nagasaki bomb was not the last shot of World War II but the first blow of the Cold War. In any case, there was no presidential directive specifically related to dropping the second bomb. The atomic weapons in America’s arsenal, according to the official order, were to be used “as soon as made ready.” The people of Nagasaki were thus the first—and, so far, only—victims of automated nuclear warfare.

What remains of the cathedral, and Nagasaki’s Urakami district, after the bomb, are visible in this post-bombing photo, which was suppressed by the US government.

Nippon Eiga Sha/NARA

The man perhaps most responsible for the Nagasaki bomb was not Truman, but Gen. Leslie R. Groves, director of the Manhattan Project. Groves had fiercely promoted using the first bomb and stifled attempts by scientists (not including Oppenheimer) to convince Truman otherwise.

Truman had never explicitly endorsed the notion of a necessary “one-two punch.” It was Groves who was the true believer and the catalyst. In the immediate aftermath of Hiroshima, he pushed for a second mission, just as the authority to carry out the attack passed to him from Truman (who was on a ship returning from negotiations with the Soviets in Potsdam). “I didn’t have to have the president press the button on this affair,” he would later boast.

The second bombing run was originally set for around August 11, which would have come a full day after Japan’s initial offer of surrender. But with bad weather forecast, Groves pushed up the mission two days, despite knowing his decision would mean rushing preparations on the Pacific island of Tinian. Another complication: Pilots had been ordered not to release the weapon until they were able to see the target with their own eyes.

Stormy conditions, as it turned out, were also forecast for August 9. The lead plane, piloted by Charles Sweeney, took off anyway despite a faulty fuel pump. When he found the primary target, Kokura, covered by clouds, he pushed on to Nagasaki despite dwindling fuel, only to find that city shrouded as well. When a small gap was spotted in the cloud cover—or so the bombardier claimed—the crew released its payload, off target but still lethal.

The bombing was preordained by Groves’ determination for what he called a “knockout blow,” which he had signaled to subordinates, including pilot Sweeney—even though Japanese leaders had barely had time to absorb the shock and devastation of the first bomb. The means to an end had become an end in itself. As Groves would later explain, “Once you get your opponent reeling, you keep him reeling and never let him recover.” Groves, noted war scholar Ian Clark, “was prepared to sacrifice all of the previously elaborated guidelines in order to implement his own strategy.”

Prior to Japan’s surrender, Truman, who’d been reading about, as he put it, “all those kids” killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, declared that no more atomic weapons would be dropped over Japan without his express approval.

Groves later had the nerve to claim in his memoir, Now It Can Be Told, that he was “considerably relieved” to learn the Nagasaki bomb had landed off target, meaning “a smaller number of casualties than we had expected.” And when reports of deaths from radiation disease emerged in the weeks after the bombings, he called it “a hoax or propaganda,” and questioned whether there was “any difference between Japanese blood and others.” He also claimed that he’d been told by doctors that radiation sickness “is a very pleasant way to die.” Matt Damon, who portrayed Groves with much sympathy in Oppenheimer, should thank his lucky stars, and Christopher Nolan, for sparing him from delivering those lines.

The Nagasaki tragedy—or war crime, if you will—might have been prevented had Truman and his aides kept closer watch on the atomic assembly line. They simply didn’t care or, to be charitable, didn’t take care. It is far from clear that the second bomb did much to hasten an inevitable Japanese surrender. Alas, none of this historical or moral complexity has made it into the final script of any Hollywood drama—not even Oppenheimer.

Greg Mitchell is the author of more than a dozen books, including Atomic Cover-up and The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. His documentary film, Atomic Cover-up, will air on PBS stations later this year.